Artist Philip Guston has been hanging around my studio, egging me on. I have loved and struggled with his paintings, and the artist’s ghost has been haunting me. So I did the only thing I could: I painted him out.

I am working on a sprawling eight-panel painting about multiple, competing truths. One of the panels—the third in the sequence—has now become my Guston. I should explain that the number of panels isn’t accidental. Eight is a recurring number in Judaism. The most obvious eight is probably the nights of Chanukah and the eight candles lit on the menorah. Each day of the holiday we strive for just a little bit more light. As an artist, too, I’m always desperate for just a bit more light—literally or metaphorically. Each night we wonder if there will be enough, then when we make it to the next day we celebrate with another candle. We’re marking time as it passes, watching the world as it changes. These eight panels are perhaps my most explicit attempt to knot together my art and my Judaism.

So, naturally, as I paint, all the great Jewish artists who have come before are here in my studio. Soutine and Auerbach are looking over one shoulder while Kitaj, Freud, Chagall and Rothko are on the other. The studio is almost a bet midrash of artists. Others come and go as well. But Guston doesn’t want to leave.

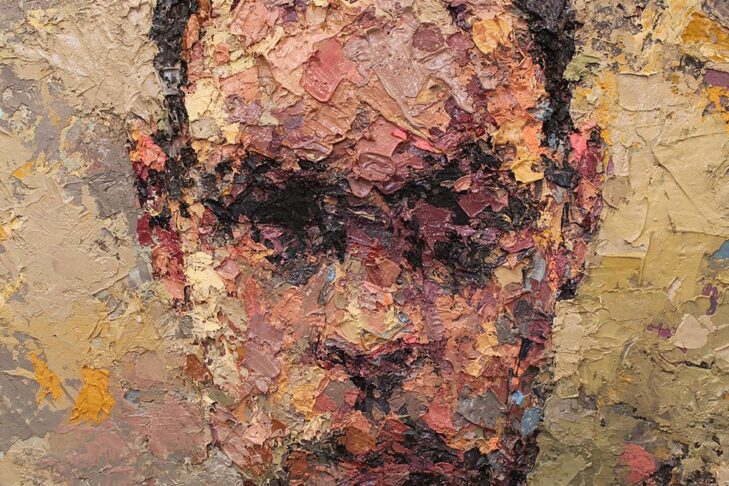

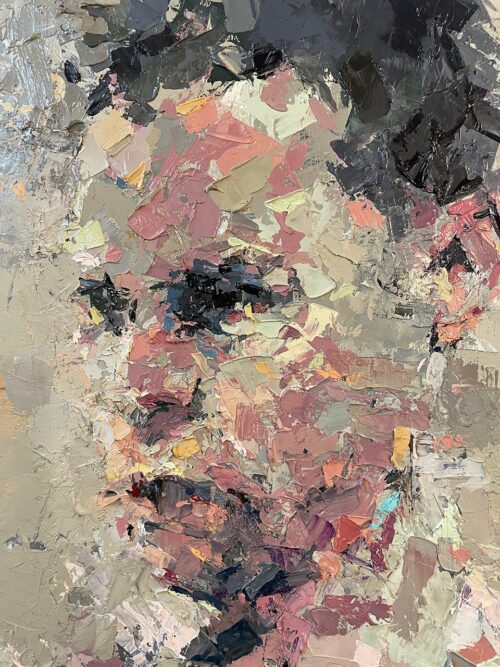

I first fell for Guston because of his sublime early work. He was a giant of abstract expressionism, alongside his childhood friend Jackson Pollock. He painted beautiful webs of color, swelling and retreating. They rustle, sparkle, flutter, float. He layers one color over another, each dab nuanced and marvelously unattainable. That is where I tried to meet him. My Guston panel builds color over color to a pink, gray and black crescendo near its center. I merged my way of painting and thinking with his. I immersed myself in his palette, reaching for him and painting his portrait abstractly.

I thought I had made my peace with Guston.

But then I started getting alerts about hostages in the Colleyville, Texas, synagogue. That isn’t too far from Lubbock, where I was born. It conjured up memories of the tragedy in Pittsburgh, just a few short years ago. The news overwhelms me with hate crimes. And Guston’s influence makes me wonder about the role of art. I want art to be timeless; art that transcends. I am uncomfortable when art and politics begin to mix. I’m with Auden who insists that poetry makes nothing happen. I’m with Philip Roth who insists that if you want to affect political opinions, write an op-ed, not a novel. But then Guston was back in my studio.

Guston’s late paintings look political and are tremendously provocative, so much so that a big Guston museum show had to be canceled last year because of politics. In the ’60s, he declared that he had enough of all that purity, and then painted Klansmen. Not once, but over and over. They are ominous yet cartoonish. He paints about the banality of evil. But the strangest thing is that they feel personal. Everything in these paintings looks like Guston—his thick and unmistakable lines become self-portraiture. The cigars look like Guston, the two-by-fours with nails look like Guston, the feet look like Guston. So, inevitably, the Klansmen look like Guston.

Guston’s radical approach to white supremacy was empathy. He isn’t just asking about politics, he’s asking about human nature. He is trying to imagine the life of a Klansman from the inside out. Sometimes these paintings are funny, sometimes they are not. Art has an ability to hold competing truths, and Judaism loves this complexity, too. We love to answer a question with a parable—from Chassidic tales to Kafka and Midrash—so we can enter and engage. He’s exploring his own inclinations. He’s asking about his own relationship to evil. What can save us, if not empathy? When the show was first canceled, my first and last thoughts were that now is actually the time when we need Guston’s art the most. The exhibit was rescheduled and has arrived in full force at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. So now is the time to confront the work.

As I work on this giant menorah-of-a-painting in my studio, it strikes me that Chanukah is a story about rededicating a desecrated temple. These aren’t just abstract ideas; in fact, antisemitism is on the rise here and now. What just happened in Colleyville, Texas, demonstrates that we are living in an age of desecrated temples. In painting, as in rededication, light is crucial. The story of Chanukah is about finding enough light to move forward through the darkness.

And Guston is still in my studio, still looking over my shoulder. These eight paintings in my studio are meant to be displayed in Boston, and I am well aware that they will be hung not long after Guston’s exhibit. Which brings me to wonder, instead of hanging in a museum, what would these paintings look like displayed inside a synagogue in Colleyville? I wonder what they would look like in Pittsburgh. I wonder what would happen if communities came together through culture and art.

I wonder if art can be a light we use to rededicate ourselves now.

“When you start working, everybody is in your studio—the past, your friends, enemies, the art world, and above all, your own ideas—all are there. But as you continue painting, they start leaving, one by one, and you are left completely alone. Then, if you’re lucky, even you leave.”

—Philip Guston, 1960

Philip Guston’s paintings are on view at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston in the exhibit “Philip Guston Now” through September 2022. My “Eight Approaches” is currently on view at Hebrew College as part of its centennial exhibition.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE