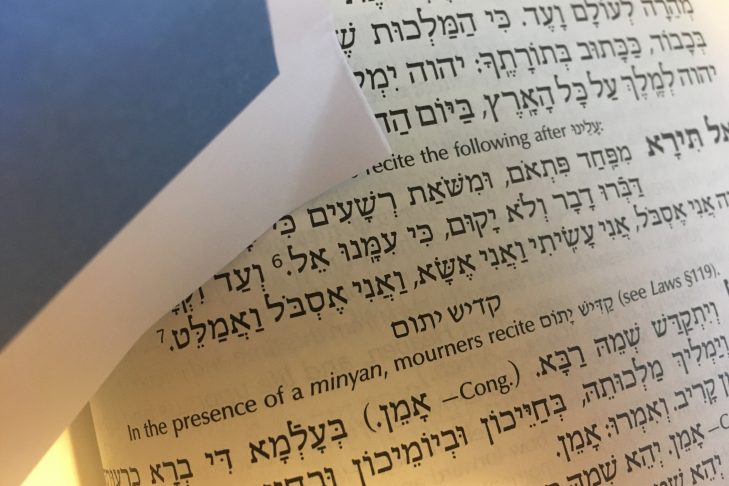

The Mourner’s Kaddish (Kaddish Yatom) has been bothering me for a while. An ancient Aramaic prayer that is traditionally said in community during certain prescribed times of mourning, it is a regular part of daily prayer. Yet this traditional prayer for the dead doesn’t mention death and barely mentions life. This oddity is often mentioned with a cluck of the, “Gosh, isn’t that interesting?” flavor. It’s hard to know what to make of it.

The bulk of Kaddish Yatom is in fact dedicated to praising the name of God, which seems like a perfectly great thing to pray, until you remember that we humans don’t know—can’t know—the name of God. It is both impossible and forbidden (hence the use of terms like “G-d” or “haShem” or יי). One of our most important and central prayers is the original mystery wrapped in an enigma.

When in mourning, we are called upon to say Kaddish Yatom five times a day, which means five times a day we essentially say, “I’m going to praise and glorify this thing I don’t know, this thing that nobody knows.” And that’s supposed to help. What does it even mean, to glorify something we are not permitted to know? It troubles me, because it feels like the moment of mourning a death should offer something more certain, something life-affirming or hopeful. Instead we’re commanded to say, essentially, “I have no idea, but I’m going to praise anyway.”

I just returned home from the funeral for a 21-year-old young man.

I think we all need to sit still with that sentence for a while.

I did not know the deceased, but we shared a community. He leaves behind a grieving, shocked family: parents, three sisters, three of his four grandparents. His grandfather—his grandfather—chanted El Malei Rachamim.

We probably need to sit with that one as well.

This bright, sweet, loyal young man died of an accidental opioid overdose. He decided last Saturday night to take a couple of pills. As his mother said, “He thought he could just try it once, without consequences.” The devastation and trauma that will follow in the wake of that risk can barely be contained. The questions of what life might have been like had he not made that foolish, understandable decision will haunt his family forever.

Soon these kind, conscientious parents will bury their child and begin saying Kaddish Yatom like they’ve never said it before. What will this mysterious prayer, this recitation of question marks, bring them?

The answer lies in the rule that a mourner cannot recite Kaddish Yatom without a minyan, a group of (at minimum) 10 people with whom to pray. Every time these bereaved parents say Kaddish for their son, they will be surrounded by people who are there to hold them up when they can no longer stand.

I hope and pray this is enough.

Zichrono livracha, may his memory be a blessing. And may families never know this kind of sorrow again.

Previously published at Jewish Themes.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE