In the aftermath of World War II, a courageous rabbi compiled lists of Holocaust survivors in Europe in hopes of connecting them with loved ones. Now, thanks to a unique partnership based in Western Massachusetts, these lists are online for anyone to search for free.

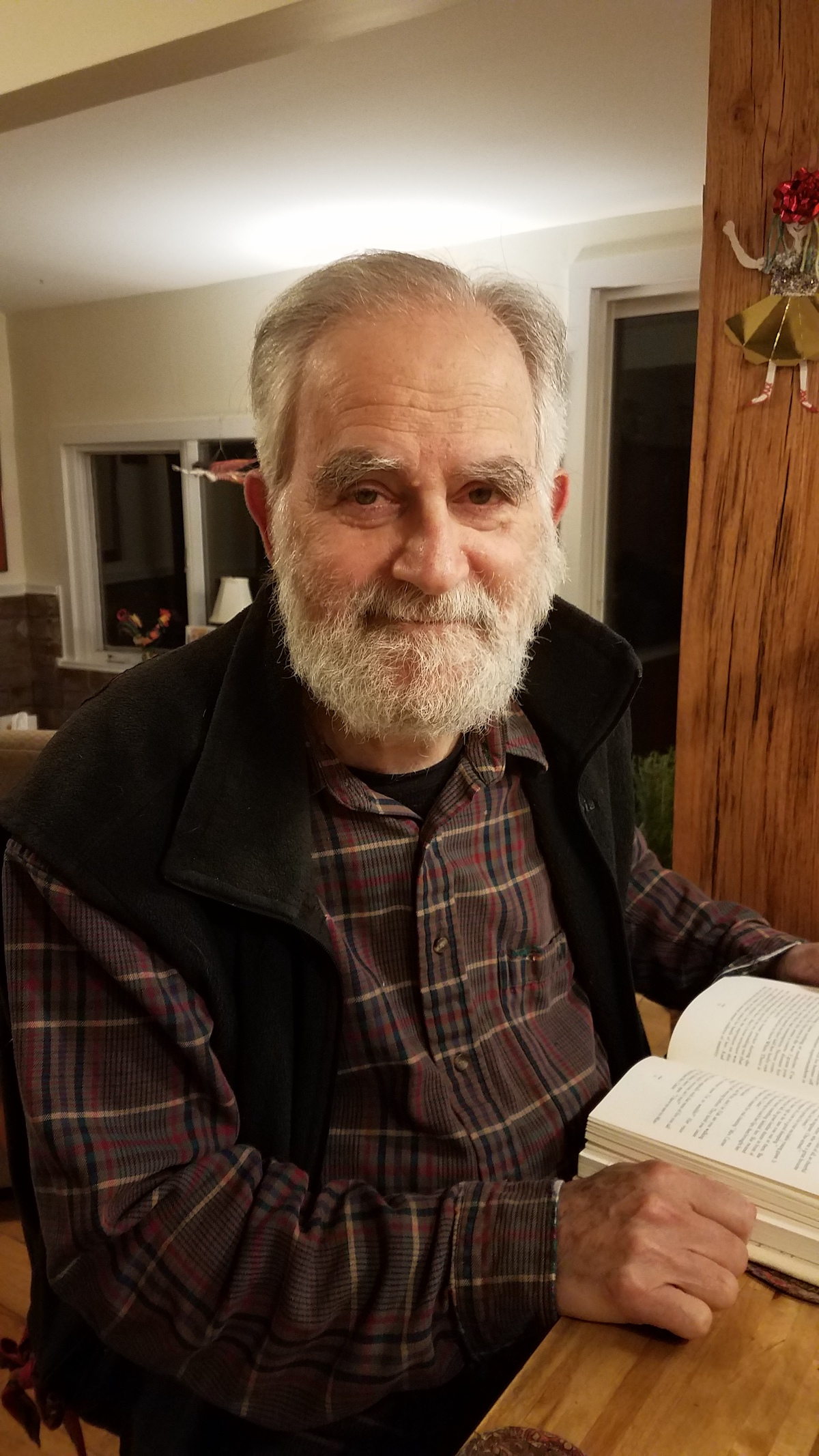

Ken Schoen of South Deerfield-based Schoen Books has digitized the lists through a collaboration with the Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center at UMass-Amherst.

“You can actually obtain a PDF of the document from the Schoen Books website under the reprint section,” Schoen said.

The digitization of the lists is a first, according to a UMass press release.

Schoen noted, “There are other resources on the web, including the portal of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum that lists survivors.”

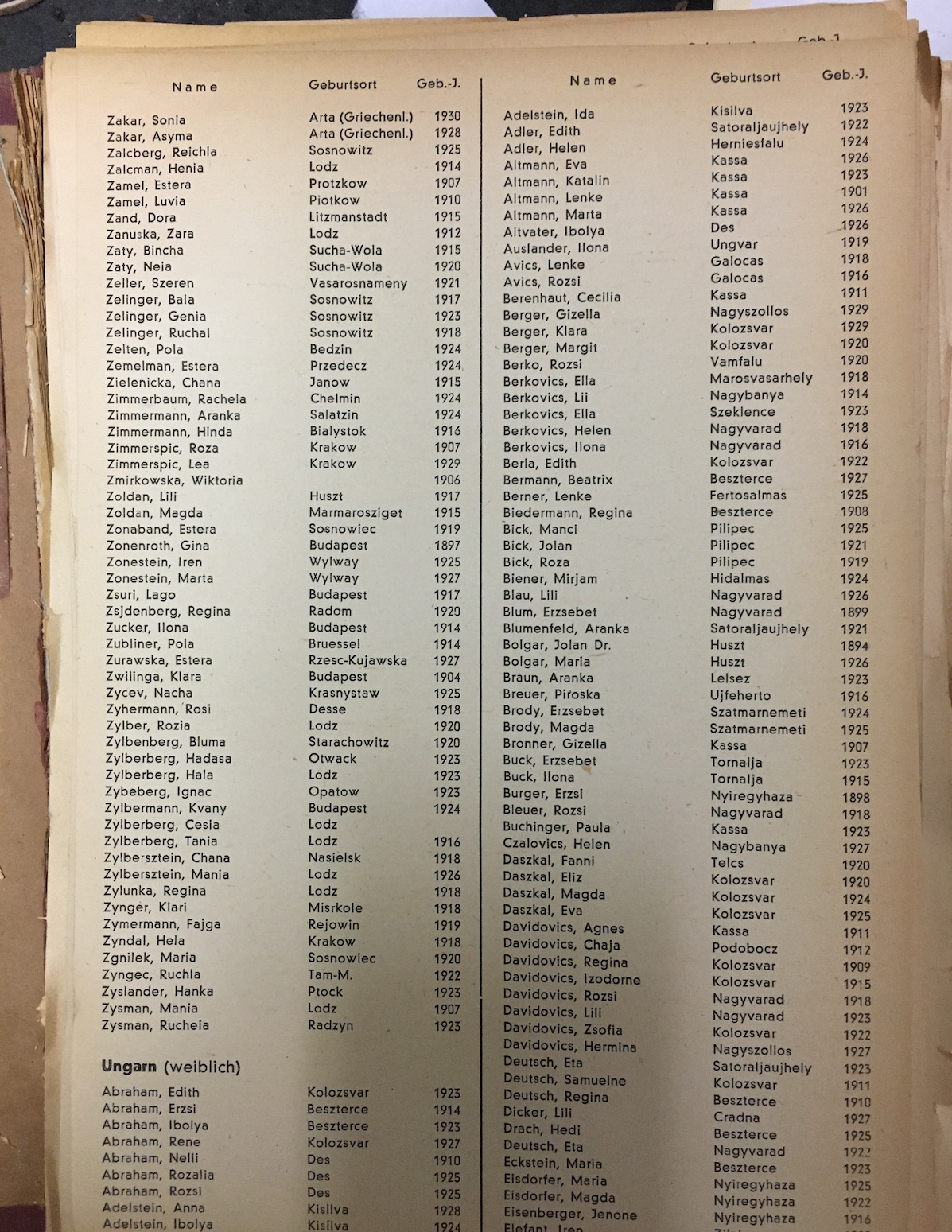

The lists that Schoen helped digitize were originally compiled almost 80 years ago by Rabbi Abraham Klausner, a U.S. military chaplain who visited war-torn Europe, including displaced persons camps for Holocaust survivors in Germany and Austria. The lists were published as a book in 1945.

“Rabbi Klausner decided he would dedicate his life to reunite survivors with their families in the Diaspora,” Schoen said. “To that purpose, he had the book published in Bavaria and sent to Jewish communities around the world for distribution.”

“It is remarkable that Rabbi Klausner and his colleagues were able to earn the trust of the survivors and compile the census,” Schoen reflected.

He estimated that 15 copies are available in libraries today. He got involved in digitizing the list when he came across one of the existing copies in a library, a five-volume set bound as one, numbering around 300 pages.

Schoen recalled that he “said to the librarian, ‘I will commit to reprinting the book.’ The librarian replied, “In that case, I will sell it to you.’”

Collective Copies of Florence reprinted the book and also digitized every page. The reprinted version is available for purchase, with the digitized lists available online through the partnership with UMass.

Schoen has been a bookseller in his current location—a converted firehouse—for over 30 years. He specializes in Judaica and books about the Holocaust. Klausner’s compilation of survivors resonated with him, as he grew up in a Forest Hills, Queens, neighborhood with a significant survivor population, and his own family had been impacted by the Holocaust.

Schoen’s father, Isaak Schon, left Vacha, Germany, in 1927 to come to New York. His mother, Betti Sternberg, escaped Herborn, Germany, in 1935 and helped her parents leave three years later, in 1938. Isaak Schon got his own parents out in 1939, but his sister—Ken Schoen’s aunt Selma—had been in a psychiatric hospital and was unable to leave the country.

“What happened next, I am sure you are all aware of,” Schoen wrote in an article on his bookstore website about a 2008 visit to Germany with his son, Seth. “She was murdered by the doctors at the hospital as part of the euthanasia program.”

“I think my father was so heartbroken,” Schoen told JewishBoston. “Maybe he couldn’t forgive himself for not getting his sister out. My daughter’s middle name is Selma. My aunt is remembered this way—Rebecca Selma. She’s not forgotten.”

Schoen’s latest project helps preserve the identities of Holocaust survivors for the public.

“I saw the value of this book to be reprinted for survivors, their children and grandchildren. If they knew the camp, the DP camp, this place their relative was in, they can look up the camp and see if their relative is listed,” he said. “They will find their relative’s date of birth and hometown and find other people who were in the displaced persons camps whose children may have stories to relate to them also.”

For many individuals in the displaced persons camps, liberation came with difficulties.

“A lot of the displaced persons did not get out of Germany until the early 1950s,” Schoen said. “There was a lot of politics and negotiations involved. They were permitted to emigrate to America through special legislation of Congress. It was not easy. It also took tremendous effort to bring many to Palestine/Israel. Rabbi Klausner also encouraged survivors to move to Palestine and begin their lives there over again.”

This resonated due to the impact of the Holocaust.

“After the war,” Schoen said, “the survivors declared, ‘We will go on and dedicate ourselves to our faith and our people. We will rebuild and recommit our lives.’”