C and Q are the call letters that ham operators use to connect with anyone in the world. The CQ call conveys precisely what it sounds like—it asks to seek you—to share a moment even with a stranger. The call also asks the open-ended question: “Is anyone out there?” Anyone sharing the same frequency—whether in the next town or across the world—can reply.

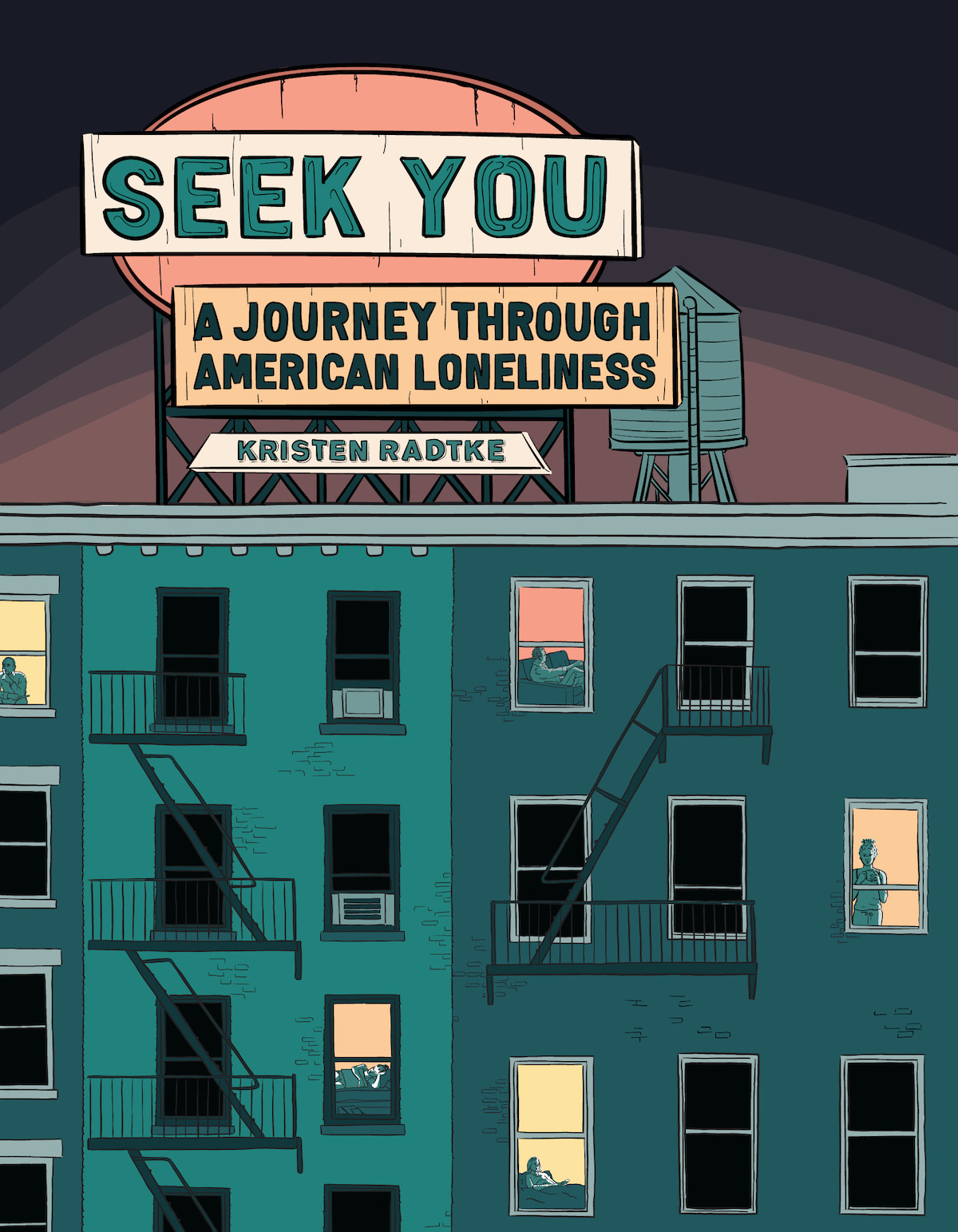

“Seek You: A Journal Through American Loneliness” is the title of Kristen Radtke’s new and excellent work of nonfiction, exploring loneliness in its various permutations. The book is Radtke’s second work of graphic nonfiction. The first, “Imagine Wanting Only This,” explored ruins and the people and places left behind in them.

Radtke’s book is memoir embedded in an extended personal essay. It is also a scientific and psychological inquiry into the quietude of solitude and the devastating effects of loneliness. Radtke interrogates the science and sociology behind loneliness as well as the influence of social media and technology in perpetuating loneliness. She devotes a section of her book called “Touch” to the work of Harry Harlow, an experimental psychologist who studied the outcomes of social deprivation on baby monkeys. Many in the field consider Harlow’s controversial methods a form of animal torture.

Radtke grew up in rural Wisconsin, which she writes instilled in her “a basic sense of unbelonging that many children are prone to feeling.” She moved to New York City in her 20s, where throngs of people surrounded her yet she still felt acutely lonely. Radtke’s drawings in shades and shadows of blues and purples capture the pervasiveness of loneliness among the crowds as well as in moments of singular desperation.

Radtke emphasizes there is a clear distinction between embracing solitude and feeling crushed by loneliness. To make her point, she quotes the writer Maggie Nelson’s definition of loneliness as “solitude with a problem.” Radtke also presents loneliness as a condition that is not innate or natural to humans. Accordingly, we’re socialized to be lonely, and to that end loneliness is a byproduct of our culture and even our politics.

The 2016 presidential election sent Radtke in search of explanations for the rise of loneliness in America. She writes, “When I started writing this book in 2016, rates of loneliness had already been increasing exponentially for decades, yet it wasn’t a subject I heard people talk about very often, at least not in relation to themselves. In the spring of 2020, isolation was imposed on all of us at once.”

Radtke recently spoke to JewishBoston about “Seek You,” the stigma of loneliness and the illusion of company we often seek to lessen our loneliness.

You address the distinction between being alone and being lonely. Did some of your findings surprise you?

Some of my findings definitely surprised me. I didn’t understand how dangerous loneliness was. Our bodies are worse at fighting disease, or we die sooner if we’re clinically lonely. I also did not understand the way in which loneliness can literally change the makeup of your DNA. It can remap your DNA. That was quite startling. But, of course, there’s an enormous difference between being alone and being lonely. Some people are very content to be alone for long periods of time and don’t experience loneliness at all. Those are some of the things I try to define in the book.

Is there a stigma attached to loneliness?

There is a stigma. Admitting that we’re lonely sounds like a personal failing or like we’ve done something wrong. It’s as if we’re saying, no one wants to spend time with me, or I have no friends, or no one loves me, which is almost never true. We’re trying to present a picture of ourselves as socially, fulfilled, in-demand people.

Your mention of the laugh track, first used to help listeners of radio shows feel less alone, is a fascinating commentary on loneliness. How is loneliness portrayed in television shows and films?

Your question speaks to my interest in how differently loneliness is portrayed in media storytelling—such as in movies and television shows—and about how men and women are portrayed differently. The male anti-hero is a reiteration of the classic, self-reliant cowboy. I’m as interested in Tony Soprano or Don Draper as the next viewer. But it’s not a new kind of character. It’s the same application of the old trope. Women don’t get that same kind of treatment on television. Of course, there are female anti-heroes, but their loneliness is presented in a slightly more tragic way than it is for male characters.

You are frequently asked questions about Harry Harlow. How did his research methods and his severe bouts of loneliness affect you?

The only thing I knew about Harry Harlow before I wrote the book was his surrogate mother studies, which you learn about it if you take a beginner psychology class. I became increasingly fascinated by his life. I wanted to read everything I could find about him, including what he published. At the time, the word “love” was not used in science. Often the word “proximity” was a substitute.

Harlow aimed to prove the existence of love with those studies. But what I think is interesting is how his studies became so dark. He fell into this pool where he was actively torturing the animals. And I think it’s interesting to hear from his former colleagues, some of whom are very disparaging about that work, and some who say he was a great person who did indispensable work. I think the answer is probably all of those things. He was married three times and from what I understand as someone who didn’t know him, he was also terrible to his wives. He was not the most supportive colleague or partner. So, I’m very interested in what he was trying to prove in his research was at odds with his life.

Can you say more?

If he’s trying to prove the existence of love, that seems to me like someone who expresses and shares love in his life. From what I’ve read, he was a very stern, detached, emotionally withdrawn person. And yet he couldn’t be without a companion. His first wife left him because he was negligent. And then he remarried a psychologist named Margaret Haney, who was doing wonderful work of her own. When Margaret died, he remarried almost immediately for the third time. He was incapable, it seems, of being alone. He couldn’t manage his life without a partner. Yet he spent his whole life isolating monkeys from other monkeys and their families.

You write that stories “are how we draw ourselves closer to one another and how we remember, and sometimes how we reshape.” Do you think stories ultimately save us from loneliness?

Stories are an essential part of feeling less lonely and feeling less alone. Seeing your experience reflected in someone else’s experience is essential to feeling like we’re a part of this world. Writing “Seek You” made me a less lonely person because I understood that my experiences with loneliness were not unique. They were very universal, and that is quite comforting. Stories achieve the same thing; they tell you that you’re not alone. And the most important thing in overcoming loneliness is knowing that you’re not alone, and that you’re seen and witnessed. Your experience is part of a larger human experience, and there is something very wonderful about that.