Among the many benefits of attending a writing residency are the serendipitous encounters with artists in a variety of disciplines. To that point, I recently met Erika Meitner at the Virginia Center for Creative Arts. I had long admired Meitner’s impressive literary body of lyrical and narrative poems—many of which interrogate her life as a Jew living and teaching in southern Appalachia, and her place as a third-generation survivor of the Holocaust.

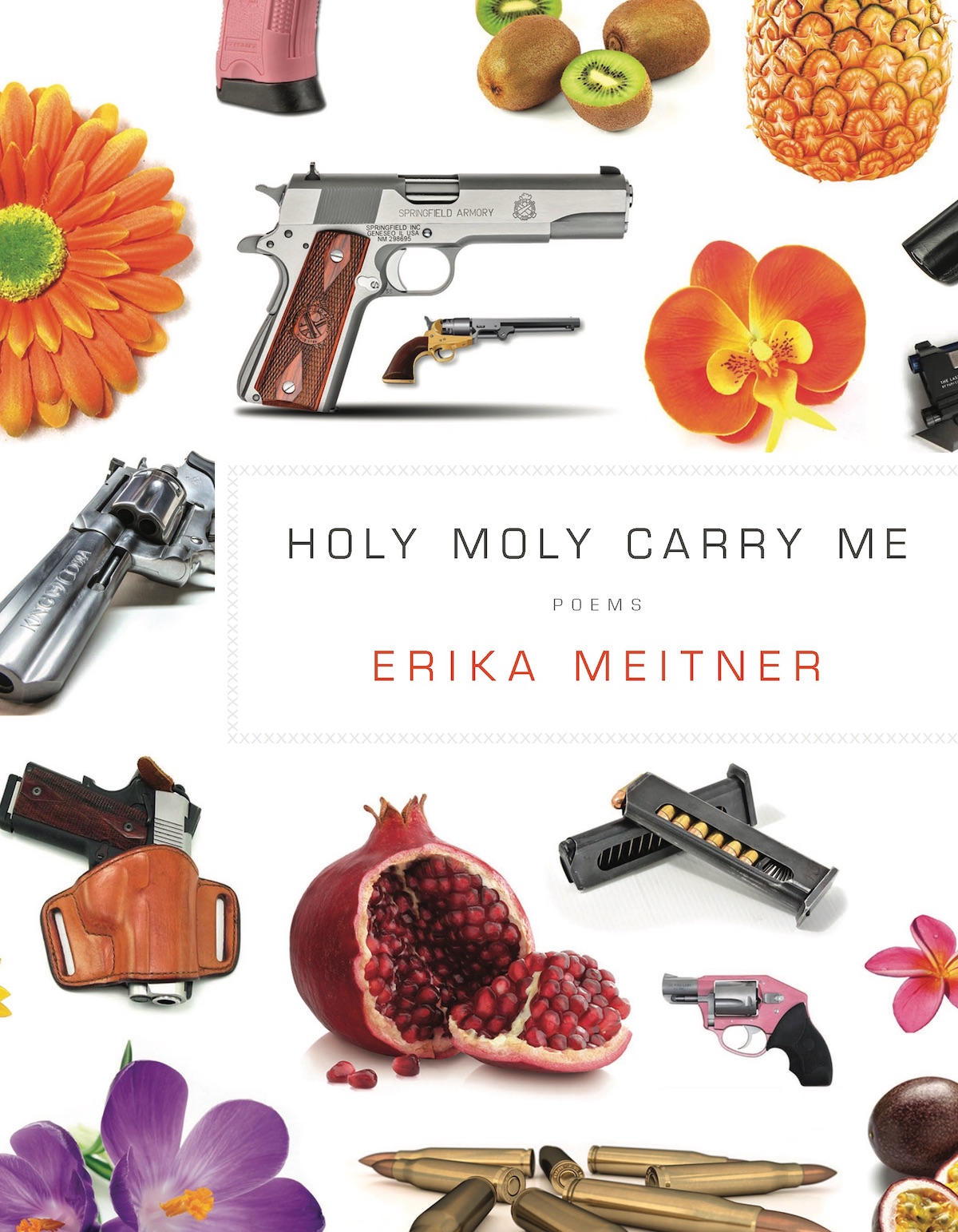

Meitner’s poetry has garnered praise and awards, including a 2019 National Jewish Book Award for her most recent volume of poetry, “Holy Moly Carry Me.” On receiving the award, she noted: “It was one of the great honors of my life. The certificate has this amazing inscription that says, ‘From the Jewish Book Council for your outstanding contribution to the world of Jewish letters and learning, and to the growth of Jewish life in America.’”

Meitner was pleased that the Jewish Book Council honored her work and that it also recognized a Jewish rural community as “a legitimate piece of Jewish life in America.” As Meitner knows well, “Being Jewish in America is also figuring out how to live with your evangelical and Christian neighbors.”

Meitner heads the creative writing program at Virginia Tech University. We recently had a wide-ranging conversation about her work, Judaism and her family’s Holocaust history.

As a third-generation Holocaust survivor, you address your family’s history in your poetry. Can you share some of that history?

My dad was born in Haifa in 1947. Right after the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia in 1939, his family moved to the Carmel in Haifa, where many German Jews settled. They were Moravian. My grandmother considered herself Moravian more than anything else. Her family had been in Prosnitz for many years, but the border kept shifting. Sometimes they were Austrian, and sometimes they weren’t. But she spoke Czech, and she always spoke German. They came to the States—to Queens, New York—when my dad was a young teenager.

And your mother’s side of the family?

My mother was born in a displaced persons camp in Stuttgart, Germany. My maternal grandparents were in five concentration camps between them. They never talked about the war when I was growing up. My grandmother lied to me and told me the numbers on her arm were her phone number so she wouldn’t forget it. I’ve met a lot of other 3G grandkids of survivors whose grandparents never talked about the war or didn’t tell them what had happened to them. They didn’t want to traumatize this new generation. So, their way of moving on was never to talk about the war.

Your maternal grandmother figures in many of your poems. What is her influence on your work?

My maternal grandmother lived to be 94. She had a lot of health issues, but they never impacted her memory or ability to speak. Her life story was so incredible. She had been a nurse-midwife in the Sosnowiec Ghetto and was one of the last people deported from there. She had taken care of all of these women who were giving birth during the worst parts of the war. She ended up at three different concentration camps, including Auschwitz. My grandparents reunited after the war. She machinated again and again so that my grandfather landed in a labor camp to have a slightly better chance of survival. They had a child before the war that my grandmother euthanized because they were throwing babies through the windows of the hospitals and of the train cars.

Can you point to a poem of yours that incorporates your Holocaust history?

The one I’m thinking of is “Yiddishland,” which takes place at my grandmother’s unveiling. It incorporates Yiddish because one of the things that happened when she died was that Yiddish went with her. My mom and aunt spoke Yiddish to each other. When my grandmother died, they didn’t have anyone to talk to in the language. There are Hasidic communities with robust Yiddish culture, and many people are relearning it now. But it’s different when it’s someone’s mama loshen—their mother language—and what they defaulted to.

What was particular about your grandmother’s burial place?

If there’s anyone who’s from Sosnowiec who is of that generation, they have a funeral plot in the same place. In that cemetery, there’s an arch that has the names of the Jews of Sosnowiec who were killed during the war or died otherwise and are not recorded anywhere else. There’s this piece in the poem about this curse emblazoned on the arch that says, “Pour out Thy wrath upon the Nazis and the wicked Germans for they have destroyed the seed of Jacob. May the almighty avenge their blood. Great is our sorrow and no consolation is to be found!”

When did your mother’s family arrive in the United States?

My mother’s family was in Germany until 1952; they couldn’t get visas to go anywhere. The American soldiers and Red Cross started requisitioning apartments from Germans and giving them to people who were in the displaced persons camps. They got a German apartment, and my uncle and grandfather had a dry goods store in Stuttgart until they got visas to go to the U.S. in 1952.

Why didn’t they stay in Germany?

I recently found my grandfather’s papers in the Arolsen Archives at the International Center on Nazi Persecution. It’s an online archive of the Nazi era. I found the handwritten forms my grandfather had filled out for the Red Cross to immigrate somewhere. It’s a heart-wrenching set of documents because it says, “Do you want to stay in Germany?” And his answer is, “Nein. There’s nothing for me where I came from, and I want to go to Palestine.” His other choices were Canada, the U.S. or Australia, but they couldn’t get visas until 1952 and went to the United States.

Your poem “HolyMolyLand” chronicles some of that history, doesn’t it?

Yes, “HolyMolyLand” begins: “Holy Moly Carry Me.” That’s why I feel so strongly about immigration and refugees, because my mother was a refugee. She was literally born in a displaced persons camp, or refugee camp, and she was stateless. Her passport lists her place of birth as “stateless.”

You were accepted to rabbinical school at one point and won a fellowship in Jewish studies at the University of Virginia. How did your work in Jewish studies influence your poetry?

I trained as a scholar of material culture and an anthropologist of religion. All the papers I wrote and articles I published during that time were about new Jewish rituals and how people enacted their Judaism through objects and rituals. It was about studying space and going into spaces. I was looking at different objects and the ways people interacted with them. I talked to people in a way that I wasn’t used to—it was almost like journalism. All of that training, I think, comes through very clearly in my poems. My poems have a lot of dialogue in them; they’re of the world.

They also have a lot of material objects in them, and they’re interested in how people live fundamentally. “Holy Moly Carry Me” in particular was a narrative study of the idea in Leviticus that “you should love your neighbor as yourself.” For example, what does that mean, and how do you enact it? And I think of that book as a Talmudic narrative answer to that question; it doesn’t give you neat answers. How do we live with other people who have different value systems and how are we in community with them? There’s no obvious answer to that.

What is your current community like?

I live in rural Southwest Virginia in a town called Blacksburg. We’re 30 miles from the West Virginia border. We have a Chabad and a lay-led Jewish community center that I belong to. This year I’m conducting Erev Rosh Hashanah services. It’s interesting to be part of a lay-led community, having grown up in Great Neck on Long Island, where you couldn’t throw a rock without hitting a shul. We were Reform, and the reason we were Reform was my mom went up and down Temple Row, where there were four temples, and asked each rabbi, “Do you allow girls to read from the Torah?” And the only one that said yes was the Reform shul, so that’s where we went.

You’re an insider-outsider writing about Christian America. And you’re the mother of a white son and a Black son. Can you share some of your personal story?

The interesting thing about where I live is that it’s more complicated than it appears. We’re an international university community, but there’s not very much critical mass in terms of Jewish families. It’s much easier to be a multi-racial family there than it is to be a Jewish family. In my poem “Dollar General,” I interrogate what it means to love your neighbor as yourself, and particularly my gun-owning neighbors and my very, very Christian neighbors, and others.

It’s also interesting to me how you adapt to place—what I call minhag hamakom, which is “the custom of the place.” We started putting up lights at Christmas because it was too sad to be the only house on the block without any. I also bake elaborate Christmas cookies, or holiday cookies, every year for the neighborhood cookie exchange. I get very competitive about my cookies.

This interview has been edited and condensed.