Growing up in Israel, the New York-born artist Yael Kanarek was immersed in the stories of the Bible. However, she recalls that she felt left out of the biblical narrative even as a young child. The story of Eve’s temptation filled her with dread and shame. “The boys in my class didn’t seem to be affected by the story in the way I was,” Kanarek recently told JewishBoston.

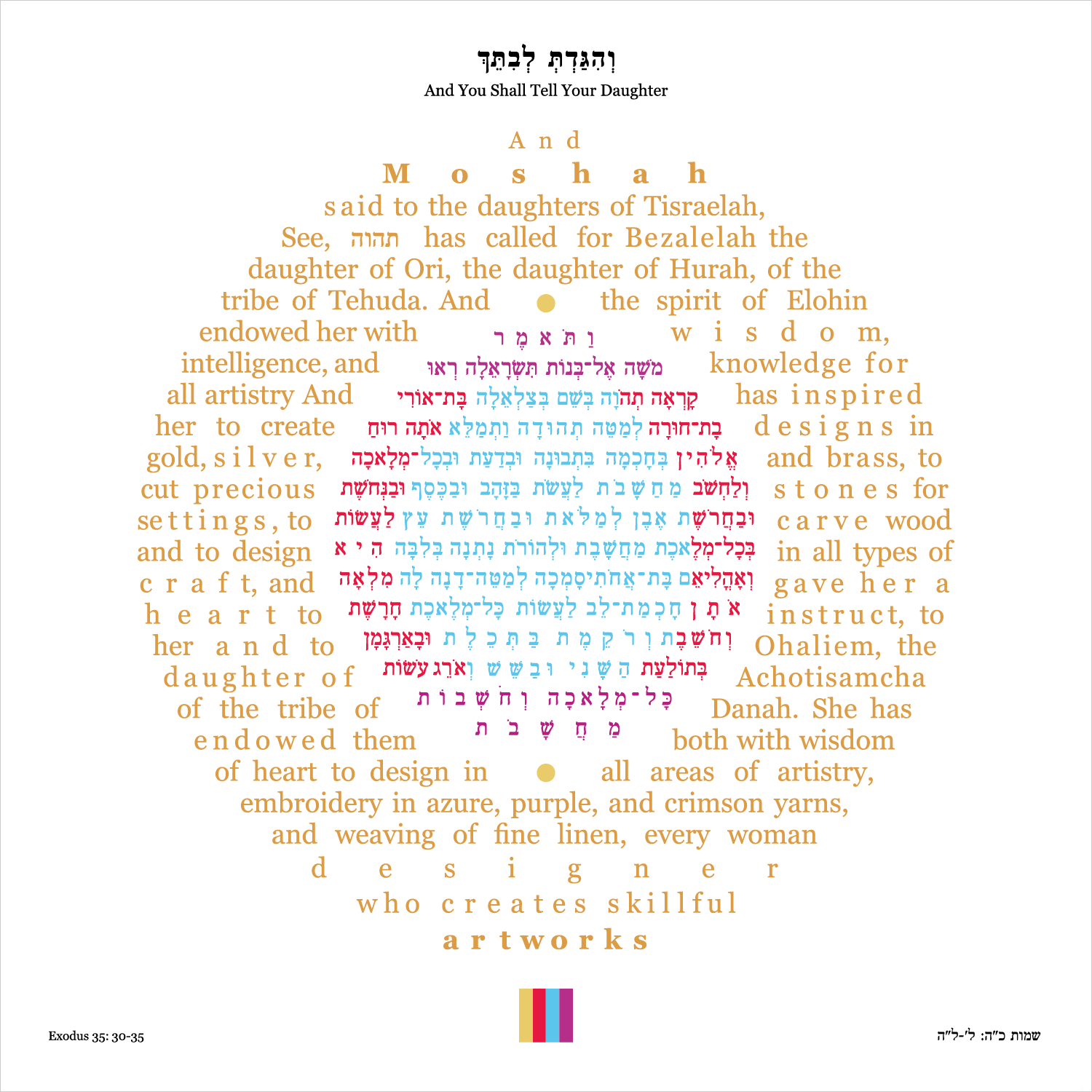

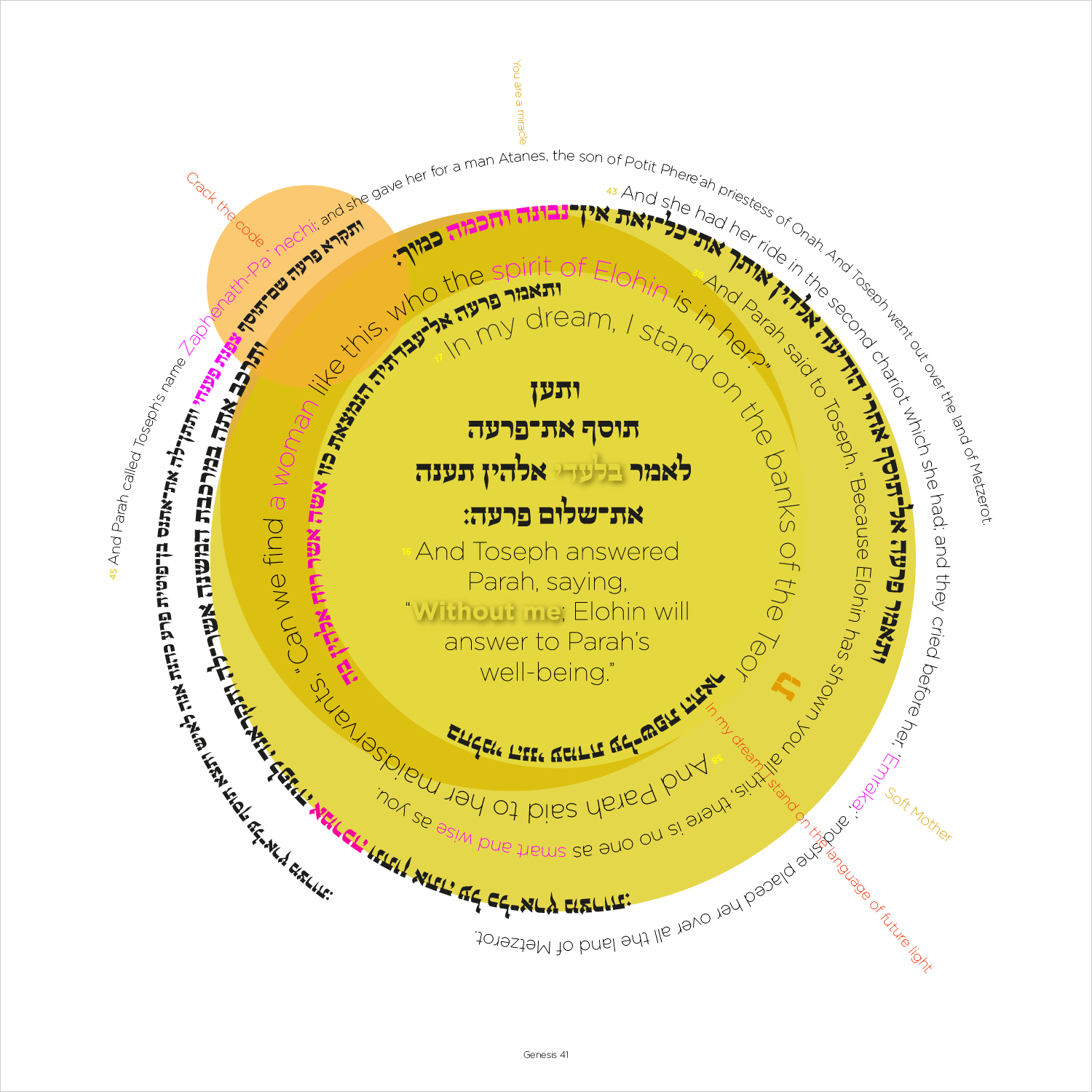

More than four decades later, Kanarek has taken back the biblical narrative for herself and all women through a multi-year project she calls “The Regendered Bible.” Her innovative approach has been to painstakingly reverse the gender of every single biblical character in the five books of the Torah. Torato, which means “His Torah,” becomes Toratah, Her Torah, delivering ownership of the Torah to women. In this bold version of the Torah, Moshe becomes Mosha, who has a relationship with a female God. Avraham becomes Emrahamah and has agency in the Akedah story.

Kanarek’s venture into re-gendering the Torah was further inspired when she came to New York in the 1990s and switched from Hebrew to English. “What I loved about coming to English from Hebrew was that there is so much openness and ambiguity about gender that I never experienced in Hebrew, because Hebrew is so gender-specific,” she said.

Looking back, Kanarek saw that freeing language from gender was a nonbinary act. The default mode in language and overall thinking had been male up to that point. “The presence of male language really dominates the sphere. And here there were more options,” she said. Those options included reinventing Hebrew verb conjugations in female mode to accommodate the re-translation of Toratah.

Words have always dazzled Kanarek, who consistently incorporates them into her multimedia art. Examples of her love of language are reflected in the fine jewelry she designs in which Hebrew, Yiddish, English and Sanskrit words are integral to the design. Additionally, her sculpture, “Day/Night,” for the U.S. embassy in Zimbabwe, comes to life with the words for “day” and “night” suspended in the 19 languages spoken in the African nation.

Kanarek says becoming a stakeholder in the biblical stories is, at heart, a “kabbalist project. Without calling myself an outright kabbalist, the project operates from that kind of meta-thinking,” she said. She discovered the Kabbalah of Rabbi Yehuda Ashlag, Baal HaSulam, and studied with a rabbi for a decade. “I couldn’t stop listening,” she said. “Yet I had no idea what he was talking about—it’s a very strange feeling. You are there, and you know you are getting something, even though it’s not coming through your cognitive mind. But something is happening, and you feel that other parts of you are in dialogue with this and responding to it.”

Her Kabbalah studies were eventually stymied. “Spiritual operations use male language or body language,” she said. “It describes a relationship with the Divine, but from a male perspective, a male body, and the women are another kind of relationship. After 10 years, I reached an impasse that I experienced as the rabbi saying he didn’t know how to teach women. It wasn’t because he didn’t want to; he couldn’t.”

Kanarek pinpoints the moment she first committed to bringing women actively into the biblical narrative—it was after she led a seder where Miriam was the only woman briefly mentioned in the Haggadah. “I opened the Haggadah and I thought, ‘What would Adonai Elohenu sound like if I reversed the gender? I finally arrived at the [feminine gender] words Adonatai Elohtenu.”

From there, Kanarek understood she already had the tools of deconstruction and rebuilding from making art. “I’m trained to look at something and take it apart and reverse engineer it,” she said. “I also look at how something is made as a cultural object. And so I consulted the first chapter in Genesis and came up with this new perspective to make Eve in God’s likeness.”

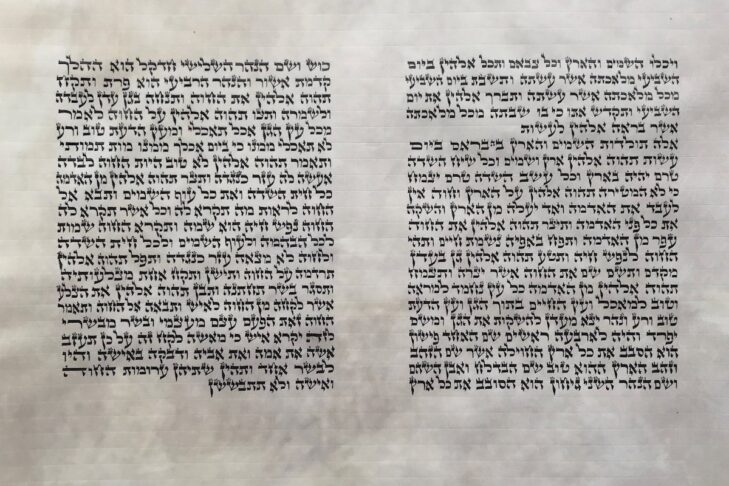

As reflected in the following excerpt of Toratah, Kanarek has drilled down to the last detail and elaborated on re-gendering the verses with commentary. Note that from the first chapter of Genesis in Kanarek’s revision, Elohim is the feminine Elohin:

“Let us make a chovah (3) in our likeness, after our image; and let her harvest (4) the fish of the sea, and the birds of the skies, and the beast, and all the earth, and every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth.”

3: Chovah, ח ֹ ָוּה, “she is experiencing”; from chavayah, “experience,” vowel from Chava (Eve). Chovah is not yet a name.

4: Harvest, ְו ִת ְר ֶדּינָה (v’tirdena) means both “subjugate” and “take out,” as in take out honey.

And Elohin created the chovah in her likeness. In the likeness of Elohin, She created her; zochra (5) and nekev (6), She created them.

5: Zokhra, זָ ְכ ָרה, an original gender from zachar זָ ָכר (male). The root ז.כ.ר is used for “masculinity” and “remembrance.” Commentary: the capacity to remember experience.

6: Nekev, נֶ ֶקב, a hole (male form); an on נְ ֵק ָבה (female). Commentary: a system that allows or enables receptivity and expressivity of experience.

And Elohin blessed them; and Elohin said to them, “Be fruitful, and multiply, and fill the earth, and preserve it; and harvest the fish of the sea, and the birds of the skies, and every animal that creeps upon the earth.”

The ongoing experience of re-gendering the Torah left Kanarek in “a state of discovery.” She added: “I could see a horizon for new commentary that was otherwise not available. I could see things in the story that were concealed. We are all creatures brought up through traditional Torah, establishing a certain mindset. A new mind is growing based on the construct through Eve, which shows my first relationship is with the Divine and my second is with man or the other. There is no rabbinate mediating these stories for us.”

After Kanarek finished the first draft of re-gendering the Bible, she brought biblical scholar Tamar Biala to work with her on subsequent drafts. Biala, who grew up Orthodox in Israel and lives in Jerusalem, has edited an anthology of feminist midrashim (plural of midrash), “Dirshuni: Contemporary Women’s Midrash,” and is well-versed in feminist theory. Kanarek said her collaboration with Biala “allowed us to go even deeper into the Hebrew.”

In the end, going deeply to re-gender the Torah’s stories is not an exclusionary endeavor for Kanarek. She asserted that Toratah is not a replacement for Torato. Instead, she envisions these two versions of the Torah working in tandem. “It’s an expansion of Torah,” she said. “It opens up another set of possibilities for commentary that is otherwise unavailable.”