I, like many viewers, discovered Jacob Geller’s video essays down the rabbit hole of YouTube algorithms. My partner and I have been watching in-depth art and video game analysis throughout the past year, but Geller’s videos easily outpace the pack. Charming, thoughtful and unapologetic with his analysis, Geller tackles the controversial field of gaming journalism by equating other works of art with lesser-known games.

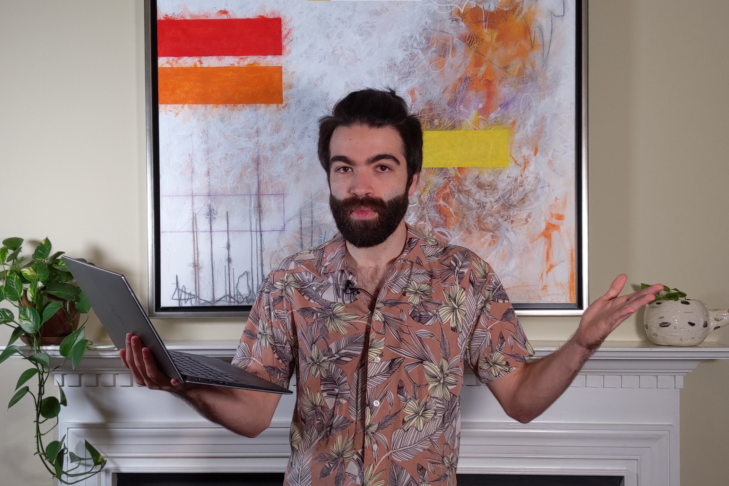

Anything from the destruction of modernist paintings to car culture to the sheer magnitude of infinity is fair game for Geller’s thoughtful comparisons, and he delivers every time. With 410,000 YouTube subscribers as of this writing, Geller is a rising star among the video essay elite, and his success is well-deserved. He is also, of course, even more lovely face-to-face (or over Zoom).

Geller’s interest in games stretches back into his youth, but he fondly remembers his first M-rated game and convincing his parents of the game’s worthwhile investment. “I had just had my bar mitzvah,” Geller told me, “and said, ‘The Torah has deemed me mature enough to play “Resident Evil.”’” Judaism and games critique have gone hand in hand for Geller, who stated that arguing about media is a very Jewish thing.

“Everyone has their own interpretation of Judaism,” he said. “The text is never just the text, and I’ve found that media becomes kind of meaningless unless you’re interacting with it critically.” Geller went on to intern at Game Informer—a taste of “real writing”—and experienced a dramatic upswing in popularity when his video on the “Shadow of the Colossus” non-existent “last secret” garnered millions of views.

When asked about the process of drafting a video, Geller takes another quintessentially Jewish approach. “I don’t really know my thoughts before I start writing, but the act of writing helps me figure them out,” he said, a sentiment no doubt shared by plenty of other writers. Geller also prefers for his videos to be separate and discrete. “I don’t do series,” he said, framing each video as more of a film than an episode of a TV show. This format allows viewers to dip into a particular topic without being bogged down by excess material, perfect for those looking for a respite without diving into a new show or movie. “You can’t really brute force anything,” Geller said of his process, which often consists of finding profound similarities between pieces of media. “You just keep playing and reading and watching things, and if you get enough similarities, you can tease out the connections.”

When asked about the difference between video game critique and critique of more traditional art forms, Geller remarked that while there are countless fantastic games writers, a lot of games writing and people who read games writing see video games as an isolated artistic medium. “Games are siloed away from other arts, and we as a group are still struggling to get beyond, ‘Should I buy this thing or not?,’” he said. The youth of the medium also comes into play, though there is value in putting games in conversation with more established media. “It’s a time thing,” he added. “There’s new ground to be broken in games journalism where there is little elsewhere.”

One of my favorite videos of his, “Judaism and Whiteness in Wolfenstein,” tackles a series of games detailing a world in which Nazism runs rampant in the 1960s, and the rebellion against this rise. When asked about being a Jewish creator who tackles these topics, Geller remarked that non-Jewish people can have a more impersonal take on such topics, which may appear to make them less biased. However, if anything, I’ve found Geller’s Judaism to add credibility to his claims, and his strong values play heavily into his work. “I think my audience knows from square one what I’m doing,” he said. “I’m not going to be coy with this stuff.”

Finally, Geller provided an honest look at the life of a content creator. “The No. 1 most desired job by kids now is ‘YouTuber,’” he said. “But it cannot be planned for and feels incredibly unstable. You have to rely on so many things that you have so little control over. It’s a machine that wants you to think it runs on serendipity, but it can rip the rug right out from under you.”