Sacha Baron Cohen remembers a book called “Our Man in Damascus: Elie Cohn” that was displayed for years on a coffee table in his childhood home in London. The well-thumbed book belonged to his late father and told the intriguing story of Israel’s most famous spy, Eli Cohen. In the early 1960s, Cohen had infiltrated the highest echelons of the Syrian government, rising to the rank of deputy minister of defense. When the producers of the bold, six-part Netflix series “The Spy” tapped Baron Cohen to play Eli Cohen (no relation), the comedian eagerly accepted. The series is the brainchild of producer Gideon Raff, whose Israeli drama “Prisoners of War” inspired the Showtime drama “Homeland.”

Eli Cohen’s story is particularly well known in Israel, and it doesn’t give anything away to point out that things ended tragically for him. Cohen was born in Alexandria, Egypt, in 1924 to Syrian parents. His life in espionage began in 1954 when he secretly aided other Egyptian Jews in emigrating to Israel. He was part of an Israeli spy apparatus in Egypt that was eventually disbanded. Cohen arrived in Israel shortly after the 1956 Suez Crisis. At the time, he tried to join the Mossad, Israel’s fabled intelligence agency, but was twice rejected.

However, in 1959, Cohen, who was then happily married to his wife, Nadia, was working as an accountant in a Tel Aviv department store when the Mossad recruited him to work as an operative in Syria. It was a difficult time for the Israeli intelligence agency, which needed eyes and ears on the ground in what was a closed Syria. Cohen was not an ideal candidate—his training was rushed, and he was overeager to please his handlers, something that could have blown his cover. But Cohen was persistent and was eventually groomed to be a Syrian textile magnate named Kamel Amin Thaabeth.

Cohen’s transformation was both a challenge and a wonder for Baron Cohen. The spy was a Sephardic Jew who often felt like a lesser citizen in Israeli society. Baron Cohen told National Public Radio: “I’ve always been intrigued by this question of identity—how people identify themselves. And for Eli Cohen, he had these two different lives. He was an Israeli second-class citizen living in poverty, and he was also, when he was undercover, a wealthy Syrian.”

Related

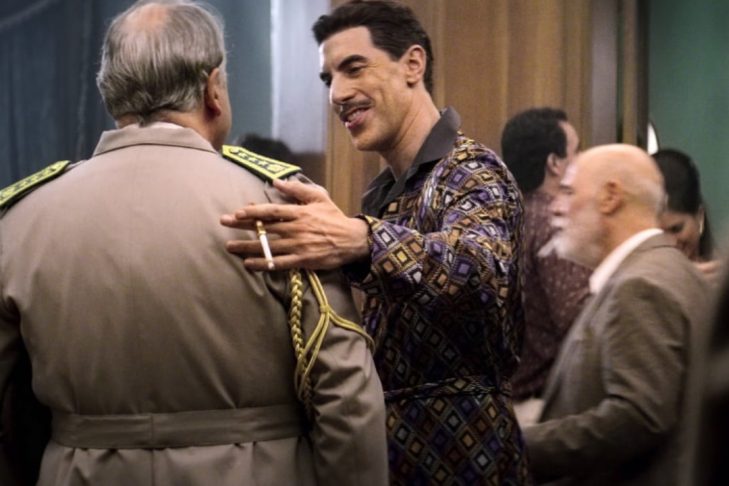

Cohen first ingratiated himself with Syrian society in Buenos Aires. He gained the trust of high-ranking Syrian officials, including the future Ba’athist president Amin al-Hafez, forerunner to Gen. Hafez al-Assad and his son, Bashar al-Assad, the current Syrian president. Cohen presented himself as a loyalist, a man who was desperate to return to his ancestral homeland. Once he installed himself in Damascus, he cultivated a high-powered social life in which he befriended the military intelligentsia and influential political friends. Cohen’s connections eventually enabled him to tour Syrian military installations on the Golan Heights. While there, he not only obtained Syrian military secrets, but he also suggested planting eucalyptus trees to provide shade to the troops. The recommendation was fortuitous—the trees provided targets for the Israeli Air Force during the Six-Day War in 1967.

In addition to being binge-worthy, “The Spy” is an excellent period piece. It captures the perils and pitfalls of conducting espionage in the early 1960s while also affecting a James Bond vibe. There’s an ever-present tension coupled with a constant sense of danger, which Baron Cohen plays to the hilt in white dinner jackets and expensive suits.

Living a double life took its toll on Cohen. He deflected his wife’s suspicions by telling her that he worked as an oversees buyer for Israel’s Ministry of Defense—an assignment that kept him away from his family for months and even years at a time. On his infrequent visits home, he and Nadia conceived two daughters, whom Cohen never knew. Baron Cohen brilliantly portrays Cohen as a conflicted, often-confused man who, at one point, reluctantly became engaged to a Syrian socialite to keep his cover intact.

In late 1964, Cohen went home to Israel for a final brief respite. The beginning of the end occurred when he returned to Damascus and transmitted Morse code dispatches to the Israelis twice a day at the same time, a deadly mistake. With the help of Russian technology, the Syrians traced Cohen’s transmitter. In early 1965, they broke into his apartment as he was sending a message to Israel.

Cohen was taken into custody, where the Syrians mercilessly tortured him and sentenced him to death by hanging in the middle of Damascus in May 1965. Fifty-four years later, Nadia, who never remarried, is still actively engaged in attempting to bring her husband’s remains back to Israel. Over the course of a half-century, Eli Cohen’s exploits have become legendary, creating a heroic story that can tend to blur fact and fiction.