“Philip Guston Now”—a retrospective exhibition of the artist’s work at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts—has opened after a two-year postponement due to COVID-19. But the controversial subject matter of Guston’s defiant and anti-racist depiction of the Ku Klux Klan was also a compelling factor.

The show was initially scheduled to open at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., in 2020, followed by exhibitions at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, the Tate Modern in London and the final stop at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. In a racially charged time that included the murder of George Floyd, museum officials requested more time to “clearly interpret” the powerful messages of Guston’s work. As a result, “Philip Guston Now” opened this past May in Boston—now first in the museum lineup—and will be on view through Sept. 11.

Philip Guston’s artistic circle once included Jackson Pollock, with whom he went to high school in Los Angeles, Mark Rothko, Giorgio de Chirico, Willem de Kooning and other notable mid-century abstractionists. At the time, Guston was considered one of the most influential post-war artists. Yet, in his later years, the themes of his work were less accepted in the art world. Ethan Lasser, the MFA’s chair of art of the Americas, sees Guston’s later lack of critical acclaim representing a fall from grace in the art world. His abstractionist work was acclaimed in the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s, but the world intruded, particularly the racial unrest and assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy in 1968. Lasser noted that as a response, Guston circled back to his early works that included depictions of KKK violence he saw as a young artist in Los Angeles.

Guston was born Philip Goldstein in 1913 in Montreal to Jewish parents who had fled pogroms in Odesa, Ukraine, at the turn of the century. Guston was the youngest of seven children and his father, Louis, worked as a mechanic for the Canadian National Railroad. Montreal’s cloistered Jewish community and the severe winters were depressing and burdensome, particularly for Guston’s father, so the family decamped to Los Angeles in 1919. In Los Angeles, the warm weather failed to lighten Louis’s mood. He died by hanging, and 10-year-old Philip found his father’s body.

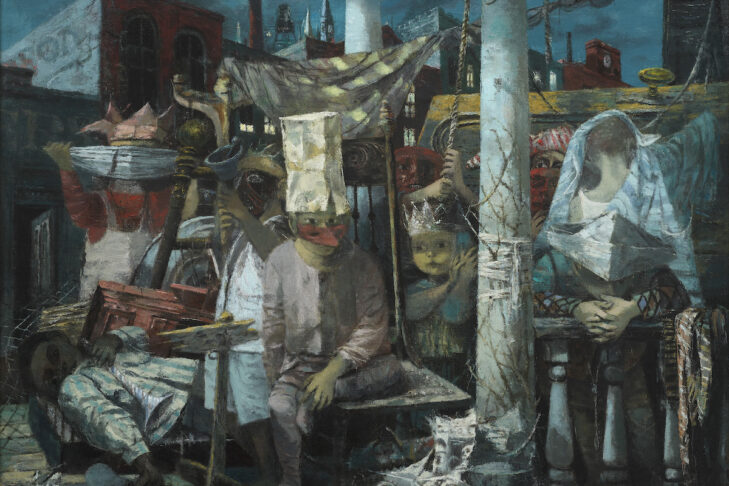

Guston’s paintings show the trauma of his father’s suicide in myriad ways. There are often ropes and bare lightbulbs in his figurative paintings. The single bulbs reference, in part, his boyhood habit of retreating to draw in a closet illuminated by a single stark bulb. The hooded Klansmen in his paintings, often cartoonish representations in his later work, are commentary on the antisemitic violence of Guston’s youth.

Guston’s painting “Porch II” brings together recurring imagery and the more salient themes of his work. Guston depicts a group of five men in front of a red building with barred windows. The space is claustrophobic. The rope, dangling near one of the men, may allude to Louis Goldstein’s suicide. Another man is hanging upside down, which exposes the soles of his shoes, a repeating motif of Guston’s evocation of the Holocaust.

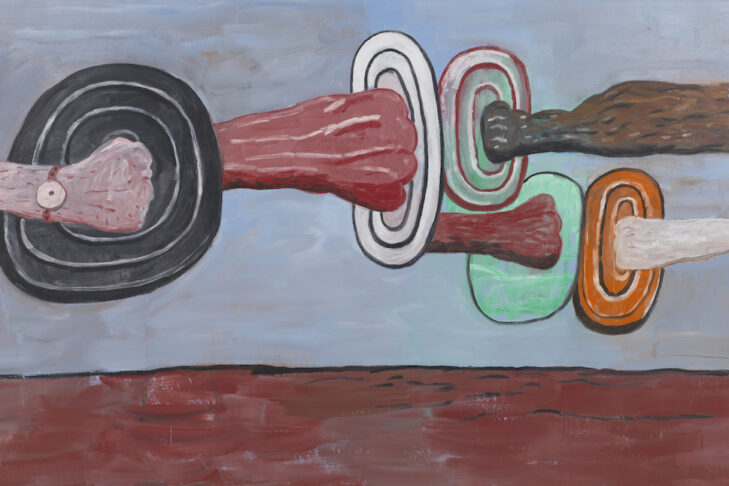

Guston first saw images of the Holocaust at an exhibition in St. Louis curated by the journalist Joseph Pulitzer. It was 1947 and Guston had an adjunct appointment at Washington University. Pulitzer had been to the concentration camps just after the war and blew up the pictures he took to mural scale. Lasser noted that Pulitzer’s exhibition immediately affected Guston, who began to paint scattered limbs and the soles of shoes. “The first time he sees images of concentration camps, he needs to respond to them in his work,” he said. “The shoes are like the light bulb for Guston. He keeps painting them.”

Guston’s earliest response to the Holocaust appears in his 1945 painting “If This Be Not I.” There is a prone figure wearing the striped pajamas of concentration camp prisoners. The figure looks as if a light bulb backlights him. It is clearly a scene of children who appear to be crowded onto a stage. “The painting is an introduction to who [Guston] is and to some of his abiding or ongoing concerns,” said Lasser.

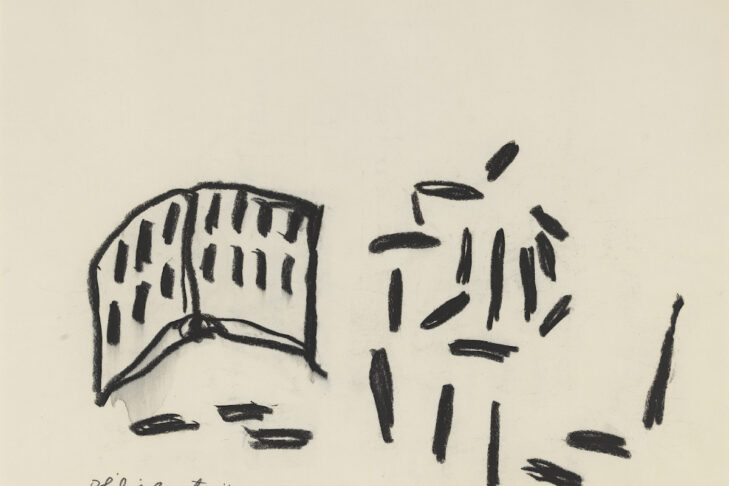

Soon after, Guston strikes out as an abstractionist, where he exhibits with Pollock, Rothko and other notable artists of the era. Guston’s abstractionist paintings of the 1950s also reflect influences of the surrealists and Italian Renaissance masters. Lasser said Guston was also beginning to embrace figurative painting. His friend and biographer, the art critic Ross Feld, writes: “The more I saw of the work that was coming from Guston in the late seventies, the more persuaded I became that he had only seemed to be an abstractionist during his earlier decades, the fifties and early sixties. That instead, like … a converso, one of the underground Jews of the Spanish Inquisition, he’d been a secret image maker all along, coerced into abstraction but never grounded there, outwardly observing but also innerly undermining its rituals.”

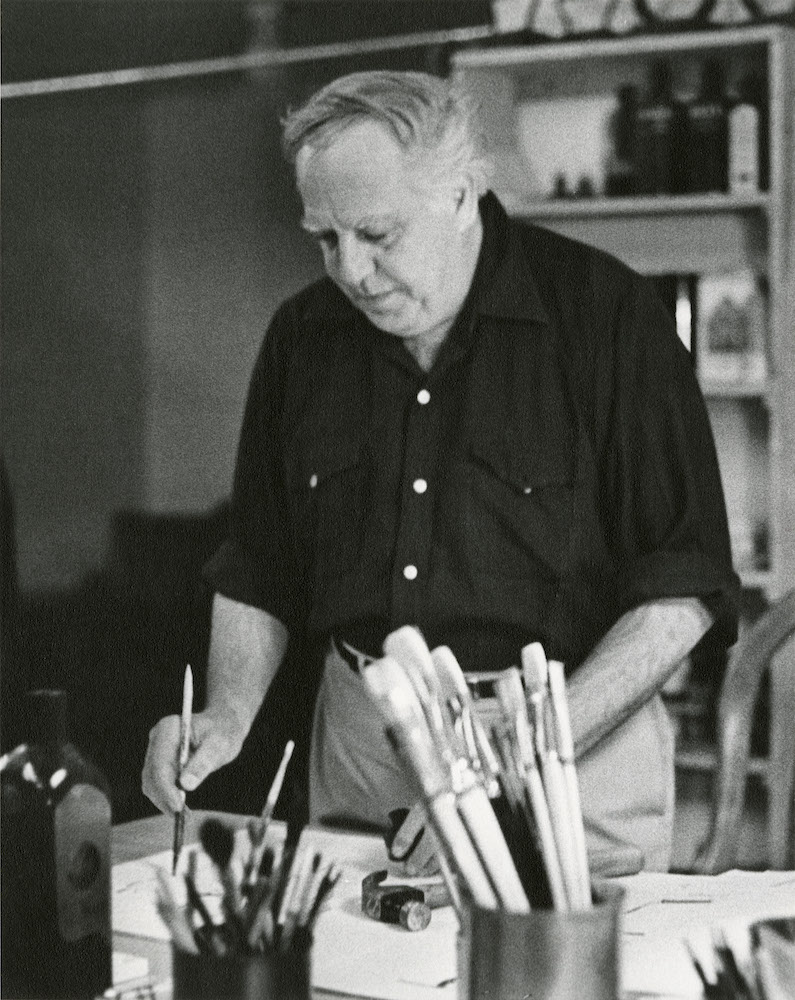

Guston’s transformation from abstractionism to realism was complete by the late 1960s. The Vietnam War, the Kent State murders and events connected to the civil rights movement deeply affected him. He had a television in his studio in Woodstock, New York, and constantly watched the news. “He wonders what it means to be a painter in that moment in history,” said Lasser.

Guston’s figurative paintings were panned in a 1970 exhibition, where the Klansmen he painted 30 years ago reappear. The most famous and perhaps most arresting of the Klan pictures is “The Studio,” in which a hooded artist is painting a hooded artist. Painter and subject become one. Critics recognize the painting as an early meta-self-portrait, in which Guston presents himself, working at his easel in the hood. He deploys the hood in past and future painterly Klansmen appearances. Puffing on a cigar through his hood, the painter keeps his hand free to create a self-portrait of his hooded persona chiefly against a backdrop of pink, Guston’s favorite color.

Hooded figures continue to haunt Guston’s later work. In “Deluge,” wisp-like hooded figures have become visible over time as the paint aged. The painting is considered a political statement against racism and white supremacy. The top half of the piece is a pinkish-red plane that doubles as a wall, which props up plates, a bottle and books. An insect lurks in the corner. Stephanie Syjuco, a commentator on the audiovisual tour of the exhibition, said “The Deluge” is overwhelming in its capacity to hold a lot, but on the surface shows so little. Lasser added that the hoods have been hidden in plain sight and suggest evil’s pervasiveness.

In “Black Sea,” Guston conjures his ancestral home of Odesa. The painting is a prescient commentary on the current situation. Viewers are encouraged to speculate on what the strange form bobbing in the sea might be. Is it a head, shoe or even Noah’s ark? The painter’s wife, Musa, is faintly outlined floating in the sea, which could also be taken for a ship. “The painting could also be considered pondering one’s heritage at the end of life,” noted Lasser.

Lasser’s assertion rings true for Guston, who died in 1980. His deathbed request to his friends, who included the novelist Philip Roth and critic Feld, was to say the Kaddish, or the Jewish prayer of mourning, for him together within an hour of his death. It’s not definitive if Guston’s wish to be memorialized as a Jew indicated a last-minute return to Judaism. However, he never abandoned his artful and personal preoccupation with the Holocaust and racism.

Yet Guston kept his audience guessing about his intentions until the end. When a journalist asked him what the shoes and specifically the piles of limbs mean in his work, he evasively answered, “The key to these paintings is the white spots, the space between them.” Noted Lasser: “He completely refuses to talk about content. He says it’s compositional; it’s a formal problem as a painter. I wish he would have said, ‘I’m thinking about the Holocaust, I’m thinking about my Judaism.’”

Yet the fact that the MFA in Boston, the city where he taught painting at Boston University in the ‘70s, originates an exhibition of an American Jewish painter is significant. Guston would likely have been pleased.