For 90 years, the Maxwell House Haggadah has been a mainstay of many American Jewish seders. It debuted when Associate Justice Louis D. Brandeis, the first Jew to serve on the Supreme Court, was 16 years into his 23-year tenure. It has been on battlefields with American Jewish soldiers since 1933 and was used exclusively at President Obama’s White House seders from 2009 to 2016.

What began as a marketing ploy became a quintessential symbol of 20th-century American Jewry. Its history is an unprecedented melding of American consumerism and Jewish observance. The Maxwell House Haggadah was the brainchild of Joseph Jacobs, who headed his eponymous advertising agency that catered to creating and selling advertisements to Jewish publications. In 1923, Jacobs approached Maxwell House (then owned by Cheek-Neal Coffee Company in Tennessee and now by Kraft Foods Inc.) about interesting Jews in serving coffee after the seder. His plan included bringing aboard an Orthodox rabbi to convince Jews that coffee beans were, in fact, fruit, and not a legume that is forbidden to eat during Passover.

Jacobs then boldly approached Maxwell House to underwrite the publication of America’s first mass-market Haggadah. The Haggadah was free with the purchase of a can of coffee, becoming an overnight bestseller. It revolutionized the American Jewish Passover celebration, including easy access to a Haggadah. It was also the first time a big corporation not owned by Jews was associated with something so prominently Jewish.

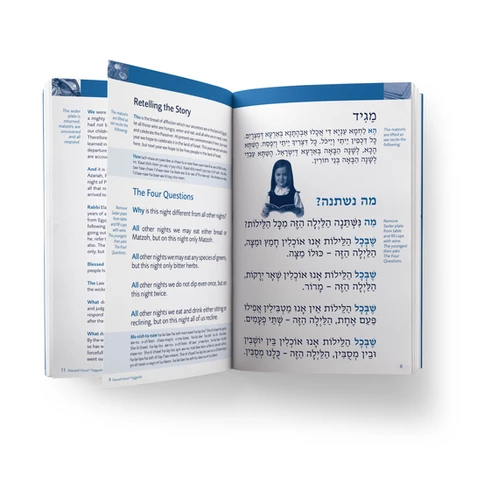

The Maxwell House Haggadah’s success rested on the fact that the Hebrew was authentic to the traditionalists. The English translation was a big draw for second- and third-generation Jews whose grasp of Hebrew was waning. The Hebrew and English appeared in parallel columns on the page, making the seder easier to follow. The Haggadah’s portability was also a plus. Children could easily hold it, and it could be easily stored. In the intervening years, the Haggadah was found on secular kibbutzim in Israel and U.S. military bases all over the world. In the 1970s, the Haggadah was smuggled to refuseniks in Russia.

Before Maxwell House went into the business of publishing a Haggadah, the Haggadah text was not uniform. Rabbi Burton L. Visotzky, a professor at the Jewish Theological Seminary, has been quoted in multiple articles about the history of the Maxwell House Haggadah saying that, “Local custom ruled liturgy. Maxwell House did more to codify Jewish liturgy than any force in history.”

Going forward, the Maxwell House Haggadah highlighted the seder’s centrality in American Jewish practice. In the 90 years the Haggadah has been continuously in print, it has undergone relatively few changes. The iconic blue cover was introduced in the 1960s and included an Ashkenazic transliteration to be inclusive. In 2000, the “thees and thous” and reference to God as a king and father were jettisoned for more gender-neutral language.

However, since 1932, the Haggadah itself has undergone several evolutions. Haggadot embrace almost every social, political and cultural issue under the sun. According to an article published by the Jewish Book Council, there are more than 3,000 versions and counting of the Haggadah in circulation, including “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Haggadah” from 2019 that used the Maxwell House Haggadah text. The impressive number of Haggadot available does not account for the self-published Haggadot and tailored family Haggadot. Yet with all the post-modern changes to the Haggadah, the Maxwell House Haggadah remains a constant, with more than 60 million copies printed and distributed worldwide.

Boston’s memories of the Maxwell House Haggadah

Most Jewish families have memories of the Maxwell House Haggadah. Rebecca Kotkin of Boston has fond memories of using it at her childhood family seders. One of the highlights was the joyful singing of “Chad Gadya” at the end of the seder. The fun ensued when a cousin insisted Kotkin’s mother mispronounced the word dizabin, as in “dizabin aba bitrei zuzei” (“my father bought one little goat for two zuzei”). Kotkin said it was a running joke for years. She now has five to six different Haggadot available at her seders so participants can choose sections and translations meaningful to them.

Newton resident Jill Goldenberg recalled that her in-laws used the Maxwell House Haggadah for years until she staged an intervention. “My kids were completely bored at the droning recitation of the [Maxwell House] Haggadah,” she said. “I argued that Pesach is supposed to be for kids and persuaded my in-laws, whom I adore, to change Haggadot. Despite the official switch, we still bring out the old Maxwell House version so my mother-in-law, in all her beautiful and strong Southern-accent glory, can recite ‘thine and thine only,’ as is her tradition.”

Jeremy Burton, executive director of the Jewish Community Relations Council of Greater Boston, did not use the Maxwell House Haggadah at his family seders but remembers his parents had a couple of copies. “My family always had a pile of Haggadot of different shapes, sizes, art and commentaries,” he said. “It was a total hodgepodge. The only constant was that they all had the full traditional text.” Burton now reads at least one new Haggadah annually ahead of the seder, which he said makes his “overall collection even more of a hodgepodge than the one I grew up with.”

Shira Goodman, chair of CJP’s Board of Directors, recalled using the classic KTAV Publishing House edition of the Haggadah, translated and edited by Rabbi Nathan Goldberg. However, she noted, “It wasn’t about the Haggadah back then but about the conversation and the singing. Nowadays, Haggadot are so much better with pictures and interpretations. We love, ‘A Different Night: The Family Participation Haggadah,’ and it has taken our seders to a whole new level.”

Elizabeth Waksman of Newton remembers her family using the Maxwell House Haggadah for years. “As kids, my cousins and I would chug our four cups of grape juice and say, ‘Good to the last drop!’” she said.

Jewish Women’s Archive CEO Judith Rosenbaum remembers her family using the Maxwell House Haggadah until her mother introduced the new Haggadah from the Conservative movement to her grandparents’ seder in the early 1980s. The Maxwell House Haggadah is a “nostalgic item that I associate with my grandparents and their Judaism, which was so proud to be American,” she noted. “In my mind, it also goes along with the Jell-O mold that was part of our Thanksgiving celebration. As a historian, I’d love to get a copy and revisit it with more critical eyes. It’s such an artifact!”

Laura Mandel’s family used the Maxwell House Haggadah for years. Mandel, executive director of Jewish Arts Collaborative, recalled that she discovered Haggadot with pictures and contemporary text in middle school. “After that, I realized why I found our family seders so boring and dry all those years!” she said. “Because of that, I have introduced ‘innovations’ to our seders, including the classic claymation Haggadah called ‘The Animated Haggadah,’ and the JewishBoston.com version. I’ve also created a custom Haggadah on Haggadot.com. But, inevitably, my dad comments on how he misses the description of Rabbi Tarfon, and we default back to Maxwell House!”

As for my own Sephardic Cuban family, we had the Maxwell House Haggadah on hand, but my grandfather, who knew the text by heart, recited it in Ladino and Hebrew. He always ended the seder declaring, “Next year in Havana!”

My husband and his brothers remember their grandfather painstakingly penciling instructions in their Maxwell House Haggadot to “Eat the egg now.” Speaking for his two younger brothers, my husband recalled that his grandparents had the traditional hardboiled egg on the seder plate and many hard-boiled eggs in a bowl. “Since the things on the seder plate are eaten at certain times of the seder,” noted my husband, “the question arose when the eggs should be eaten.”

Wishing you all meaningful seders, with whatever one, two or three of the many thousands of Haggadot you use. May you spend next year in your happy place. And, for goodness’ sake, don’t forget to eat the egg at the right time—whenever that may be.