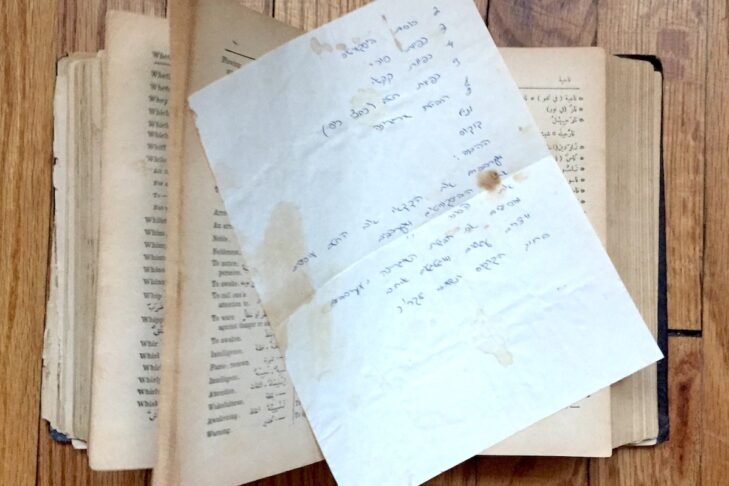

Recently, I was ruffling through my grandmother’s precious Arabic-English dictionary when I found a stained scrap of paper nestled amongst the pages. Written in beautiful Hebrew script was a recipe for chocolate balls, a simple, kid-friendly dessert that my aunt and cousins continue to make to this day. The discovery filled me with emotion. As I read through the recipe, I could feel the love with which my grandmother wrote it down. When I excitedly showed it to my aunt, she regretfully informed me that it wasn’t my grandmother’s handwriting at all. I was disappointed to learn this, but somehow it didn’t take away the wonder and connection I feel when I see and touch this piece of paper, which I still keep in the dictionary.

In a parallel experience, I’ve been working with my sister to decipher a series of letters that my grandfather wrote to my grandmother in the ’70s. It’s tricky to understand because the handwritten chicken-scratch flows seamlessly between Hebrew, Arabic and even a few English words. Throughout the letters, my grandfather discusses the mundane details of his life in Connecticut, at one point referring to my aunt as “Sheikhah Al-Hara” (the elder of the alley) as she rode her bike with the American neighbors she befriended. In reading this, my sister and I delighted in the crystal clear vision of the Bridgeport house we remember visiting often as children, the splintery wood of the wrap-around porch, the smell of the nearby lake, the joy of catching fireflies on warm summer evenings.

Later, when discussing these letters with my aunt, she informed me that at the time this letter was written, they weren’t living at the house we remember in Bridgeport; they were living at a different house in Seymour. Despite the whiplash, I could still feel the warmth, nostalgia and groundedness that I felt during that initial, misguided reading.

Each year, as we recount the Passover story, we are told to imagine that we ourselves were slaves in Egypt and crossed into freedom—and the seder allows us to access this experience through the senses! It’s why we taste bitter herbs and salt water. It’s why we sometimes whip each other with scallions. It’s why Iraqi children adorn themselves with old rags, scarves and torn clothing to emulate the supposed look of our ancestors as they left Egypt. It’s also why I made my own matzah this year, utilizing Emmer flour, the heirloom strain of wheat thought to have been most common in ancient Egypt, and likely what our ancestors made their matzah from.

I take delight in this meeting place of research and guesswork. While the facts of our families’ stories are incredibly important, it’s the element of curiosity and sensory experience that make a story come alive, whether or not they are precisely historical. In this way, we allow our imagination to make history feel real and full of emotion. We are able to indulge in our fragmented stories, even if the pieces don’t fit perfectly together.

I’m in the process of writing songs that lean into the ambiguity of our stories and embrace the way the senses color in our memory. As I steep in my imagination, I’m beginning to imagine the cool feel of rushing water in the Tigris, the smell of fragrant spices in the market and the sound of voices and instruments of generations past ringing out in praise and joy. I hope when you hear my music, you’ll be able to experience some of these senses along with me, allowing imagination to perfume the memory of your past as well.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE