In 2014, the murder of Eric Garner at the hands of a police officer was caught on camera, barely 10 minutes away from where my family lives on Staten Island.

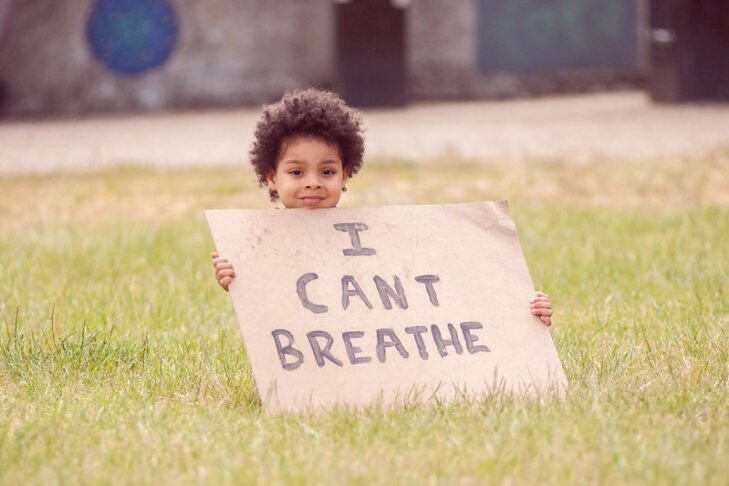

In the bystander-caught video, you can hear Garner gasping, “I can’t breathe,” 11 times as he lies with his face pressed into the sun-baked concrete. He lay unconscious on that sidewalk for seven minutes as police officers, and eventually EMTs, stood by.

His alleged crime? Selling loose cigarettes.

Daniel Pantaleo, the police officer who put Garner in a chokehold prohibited under NYPD regulations, had already been sued by three men over allegedly unlawful arrests of Black Staten Islanders in the two years prior to his run-in with Garner.

In the first case, Pantaleo was accused of arresting two Black men in their 40s without cause, and subjecting them to a strip search out in the open on a local street. The lawsuit was settled by the city for an undisclosed sum, and Pantaleo stayed on the job until he was fired for his use of the chokehold on Eric Garner in 2019, five years after the fact.

In 2015, I cast my ballot in a special election for my congressional representation. The man who went on to win the seat, Daniel M. Donovan Jr., was the same district attorney who failed to secure an indictment from the grand jury for Pantaleo. Garner’s killing, in a place so familiar to me—the place where my father grew up, my own congressional district—hit close to home. His final words, “I can’t breathe,” haunt me to this day.

Almost six years after Garner uttered those words, another unarmed Black man would be murdered over a thousand miles away, in Minneapolis, face pressed into the pavement with a knee on his neck.

His crime? Allegedly passing a fake $20 bill at the corner store.

His last words? Like Garner: “I can’t breathe.”

George Floyd’s murder led to an outpouring of anger and grief, with Americans of all races taking to the streets. Mass protests rocked the country. And Minnesota’s governor handed over the prosecution of Derek Chauvin, the police officer who knelt on Floyd’s neck for 9 minutes and 29 seconds as bystanders begged him to stop, to Attorney General Keith Ellison, citing Minneapolis’ state representatives’ lack of confidence in county-level prosecutors.

The name George Floyd would become synonymous with a societal awakening about police brutality. His death became the catalyst for the most ambitious legislation tackling policing reform in my lifetime, the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act.

As the verdict was announced in that Minneapolis courtroom, I broke down in tears. It should have been a foregone conclusion that Derek Chauvin, who was fired from the police force shortly after Floyd’s death, would be found guilty on all charges. After all, we all saw the video of him kneeling on Floyd’s neck as Floyd’s life drained out of him.

But the verdict wasn’t foregone at all.

Accountability for state and extrajudicial vigilante violence against Black people has not come easily in America. Lynching has not yet ceased to be part of the fabric of the Black experience. How often it happens, we do not know—no comprehensive statistics exist. But we do know that even where graphic proof has existed, criminal charges, much less convictions, have been nearly impossible to attain.

In 1955, 14-year-old Emmett Till was abducted from his great-uncle’s house and lynched after allegedly sexually harassing a married white woman in a Mississippi store. The woman’s husband, Roy Bryant, and his half-brother, J.W. Wilam, beat, tortured and mutilated the teen before eventually shooting him in the head and sinking his body in the Tallahatchie River. Decades later, Till’s accuser recanted.

At Till’s funeral in his hometown of Chicago, his mother, Mamie Till Bradley, insisted on an open casket. “I think everybody needed to know what had happened to Emmett Till,” she told PBS.

Yet a jury would acquit Till’s murderers, who months later were paid a handsome sum of money to publish their graphic confessions in Look Magazine. The jury, for their part, claimed that they would have returned a “not guilty” verdict even faster had they not stopped their deliberations for a soda break.

Sixty-five years later, we watched as another verdict was returned quickly. But this time, it was a resounding “guilty on all charges.”

Derek Chauvin’s bail was summarily revoked and he was led out of the courtroom in handcuffs. This time, everybody knew what had happened to George Floyd—and the man responsible was held accountable.

But the verdict was not justice. It was just a collective scream of enough.

Gianna Floyd, Floyd’s 6-year-old daughter, famously said while participating in the protests in the wake of her father’s death last summer: “Daddy changed the world.” This change is only just starting to unfold.

“Tzedek, tzedek tirdof”—“Justice, justice shall you pursue,” the famous words from Deuteronomy, has become something of a rallying cry of Jewish activism. The verse in full reads: “Justice, justice shall you pursue, that you may thrive and occupy the land that the LORD your God is giving you.”

The pursuit of justice isn’t a choice. It is the condition of moving beyond mere survival into thriving. Justice is on the horizon and every last one of us is called forward to improve material circumstances not just for ourselves, but for everyone who lives among us.

Chauvin’s conviction is not the end of the pursuit. Rather, it must be seen as just another beginning. Since George Floyd’s murder, 181 Black people have been killed by police in America. Just as the verdict was being handed down in the Chauvin trial, Makiyah Bryant, a 15-year-old Black girl in Columbus, Ohio, was shot dead in the street by the police.

On Thursday, Duante Wright, shot last week during a traffic stop miles away from where Chauvin was sitting trial, will be buried. George Floyd’s girlfriend, Courteney Ross, knew Wright—she was a dean in his high school. The officer who pulled the trigger has been charged with manslaughter. The police chief has resigned.

Chauvin’s conviction may represent a turning point in holding police accountable for the deaths of so many Black people, which the prompt laying of charges against the officer who shot Wright suggests. That officer will face a trial. Evidence will be presented. A jury will deliberate. And perhaps, like in the Chauvin trial, a guilty verdict will be returned. But once again, this is hardly a foregone conclusion. Accountability in the extrajudicial killings of Black men has never been guaranteed.

But even if she is found guilty, holding police accountable will never be synonymous with justice. Nothing short of addressing the material conditions of Black Americans that have led to these violent encounters can ever be.

And so as we breathe a collective sigh of relief over the Chauvin verdict, let us gird ourselves for the fight ahead against systemic racism in all of its dimensions.

Tema Smith is a contributing columnist for The Forward and the director of professional development at 18Doors.

Reprinted with permission from The Forward.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE