Joy Ladin, the David and Ruth Gottesman Chair of English at Stern College for Women at Yeshiva University, is the first openly transgender professor in an Orthodox institution. The recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in creative non-fiction and a Hadassah-Brandeis Institute Research Fellowship, she has published an award-winning memoir, “Through the Door of Life: A Jewish Journey Between Genders,” numerous essays and 10 volumes of poetry.

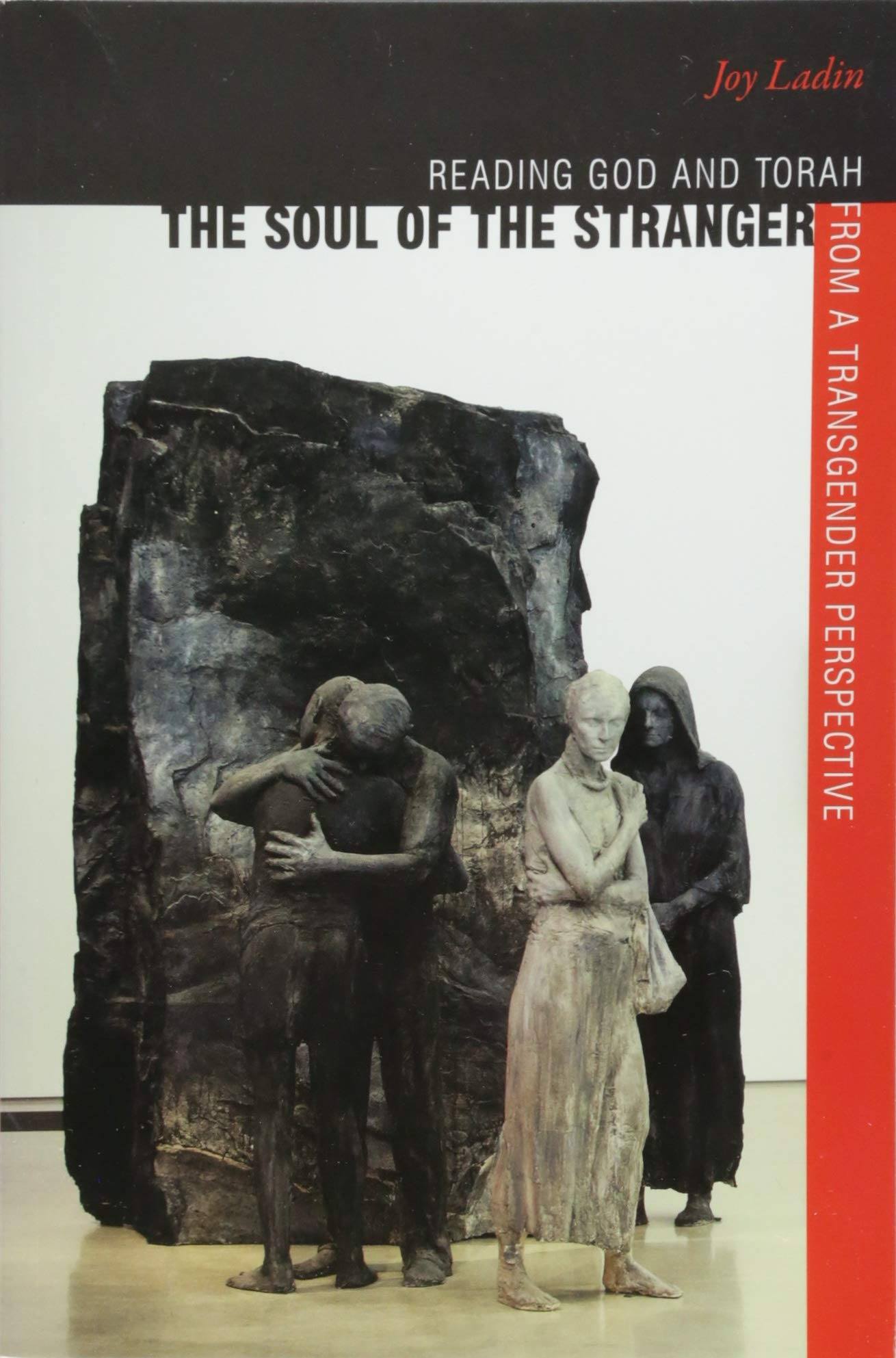

Ladin’s stunning new book—“The Soul of the Stranger: Reading God and Torah from a Transgender Perspective”—embraces various genres. To call the book a strictly academic work is to do a disservice to her unique reading of the Torah. Ladin’s aim is not to “queer” the Torah, but to bring forward its inherent humanity using a transgender lens.

Ladin recently spoke to JewishBoston about her new book, her experiences as a transgender child and her mid-life transition. What are some of the highlights of your life story that appear in “The Soul of the Stranger?” I grew up as a trans child in hiding, even though I didn’t have access to the word “transgender.” I grew up knowing my sense of who I was, was quite different from the way people saw me in terms of gender. I didn’t even have the word “gender.” I knew that nobody in my family or anywhere in the culture had words or ways to understand who or what I was. I assumed that I was something unspeakable. If I revealed my female gender identification to the people around me, I would be attacked or exiled. I focused more on that if people knew who I really was, I would not be lovable. I would be monstrous in some kind of way, and beyond their love. I felt my life both practically and emotionally depended on hiding who I was. When I was a young, I read an article about a mother whose child was born male and living as a woman. That article gave me the word “transsexual.” It showed me a mother who loved her child regardless. But I didn’t read this piece and say, “I should talk to my mother.” Instead, I continued living with my fear. But now I had hope for some kind of future where I could go through this process. In the language of the article, it was not about gender transition. It was not living as a woman but becoming a woman. As I got older, I realized I could choose that life if I wanted to. I made my transition in my mid-40s as a father of three, and I was stunned over and over by people who were accepting or kind or generous to me. They may not have understood what I was going through, but their impulse was to be nurturing. That was an incredible experience. “The Soul of the Stranger” is a book that defies genre. It features original scholarship, memoir and creative non-fiction. How did you balance these genres? I first thought about this book when I applied for a research fellowship at the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute. HBI was looking for an academic project and accepted my proposal for a very academic book. At the same time, the National Endowment for the Arts awarded me a fellowship for creative non-fiction. That changed things, so the book also had to be creative non-fiction. That was the whole mix of pressures and functions that went into writing the book. I used all these different approaches to figure out something that I thought would be simple for me! I had to read the Torah from a transgender perspective. When I started writing, I had no idea what that meant or how to make it meaningful to other people. I had some false starts before I realized it had to be written to the broadest audience possible. You present a number of biblical characters through a transgender lens. For example, Adam is human before he is gendered. Abraham defies his role as a son and leaves his father; Jonah refuses the role of prophet he’s been assigned. As I was writing this book, I realized there was a fundamental choice I had to keep making. There are two different ways people think about trans identity. One is as a form of queerness defined by their differences or particularities. It’s about the ways they defy norms. Other trans people are transsexual people like me who are born into one gender and identify with the other binary gender. I didn’t grow up wanting to be queer. I didn’t want to defy norms; I wanted to fit into norms. That’s common among transsexuals of my generation. When I was writing this book, I realized that as a trans person I was stuck in this queer position I never wanted. But I also noticed that most of what I experienced as a trans person was common to human beings. I was far from the only middle-aged person undergoing a transition in midlife. These things were quite common. I also realized I wanted to write about trans identity in relation to the Torah in a way that would offer people this insight—being trans is a way of being human. Articulating the trans experience, the trans perspective or trans insights is articulating human perspectives and human insights. Is there anything else you would like to add to our conversation? After spending the whole book generalizing the trans perspective, I suddenly say how trans people might feel when reading the most clearly gender-binary part of the Torah. I begin making arguments for being able to see gender in different ways. I had been avoiding the laws based on gender. If you are a religious trans person, when you encounter those parts, what do they mean? Are these places where I’m being told in this text that this tradition is not for me? Is there some way to experience this as a trans person? That was a challenge I couldn’t avoid—I dove into it head-on by looking at the census laws. Those laws are all about identifying people as male. They come with completely binary assumptions; therefore, does this speak to any part of my life as a trans person? On its face, it’s erasing the possibility of my existence. It assumes so profoundly you can immediately identify a person as one gender. Those laws, however, were doing the opposite. We’re in a transitional time in our culture where more people are aware that binary gender is a problem for some people. For some of them, it implies, “Let’s not talk about it; let’s pretend it’s not there.” It’s a common place we get stuck in. One of the powerful things about the gender-based laws in the Torah is that they speak to trans people. The Torah puts the role of sex in shaping lives and destinies front and center. The Torah doesn’t care how people feel about that. I find that as a result, the Torah speaks to my experience of gender in unexpectedly direct and powerful ways. This interview has been edited and condensed.

Related