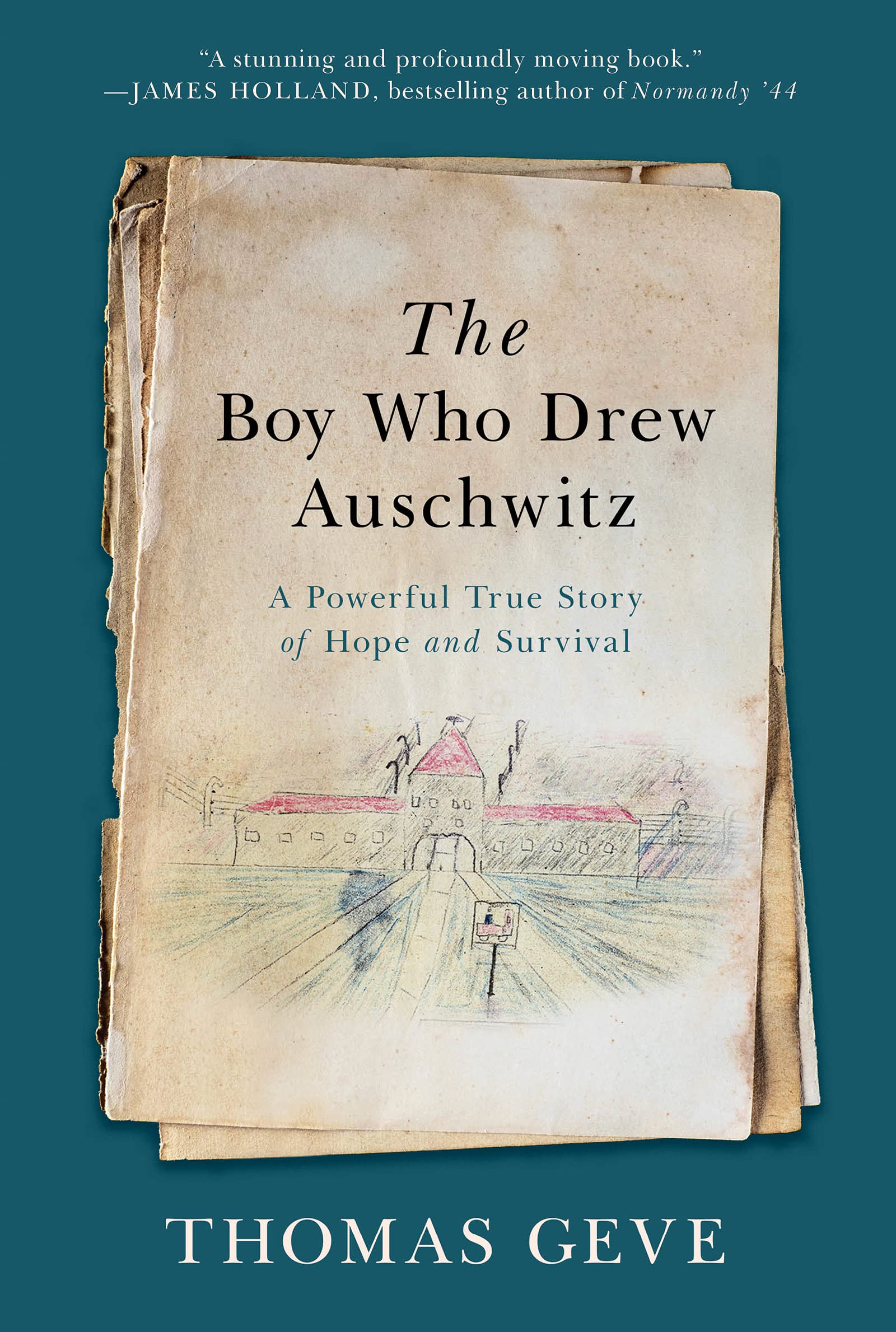

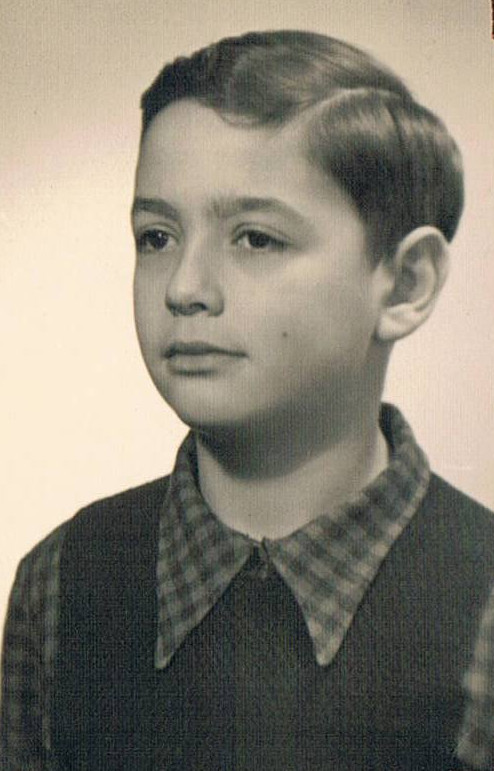

When he was just 13, Thomas Geve entered Auschwitz. To make sense of his terrifying surroundings, he began to draw. Now he’s 92, and these drawings are compiled in a powerful new book, “The Boy Who Drew Auschwitz: A Powerful True Story of Hope and Survival,” co-authored with Charlie Inglefield, a journalist who became captivated by his story on a museum visit in Switzerland.

After liberation, Geve went to Switzerland, living in a home for orphaned Holocaust adolescents. He located his dad in 1945 and moved to London to finish high school and college. He then moved to Israel, worked as an engineer, served as an officer in the army, married and had kids—and wrote and lectured about his experiences for decades. Two previous iterations of the book were published in the 1950s and 1980s.

The updated version contains Geve’s recollections and 56 color etchings of time spent in three concentration camps—Auschwitz, Gross-Rosen and Buchenwald, where he was left to fend for himself. JewishBoston talked to Inglefield about the book.

How did you come to collaborate on this book?

This came through the most random of circumstances. I’m more of a sports journalist by trade, rather than investigative. In March or April 2019, I was doing some freelance work for a client in Switzerland. I learned of an exhibition called “Children of Buchenwald” at the Burg Museum in Zug. I didn’t even realize there was a museum in Zug, let alone an exhibition like this; it’s a sleepy little expat town outside of Zurich.

I was trying to understand Switzerland’s involvement or lack of involvement in World War II; you know, it was something quite unusual to learn about. [The exhibit was] basically drawings from kids. I think 107 children were sent to a youth home, Felsenegg, at the top of the mountain. Thomas was one of the kids who was sent over by charities associated with the Red Cross during the summer of 1945. It gave boys and girls like Thomas a chance to start their recovery, start their rehabilitation. Those Alpine hills are gloriously beautiful in the summer. There was an opportunity for them to try and get back to some kind of semblance of life.

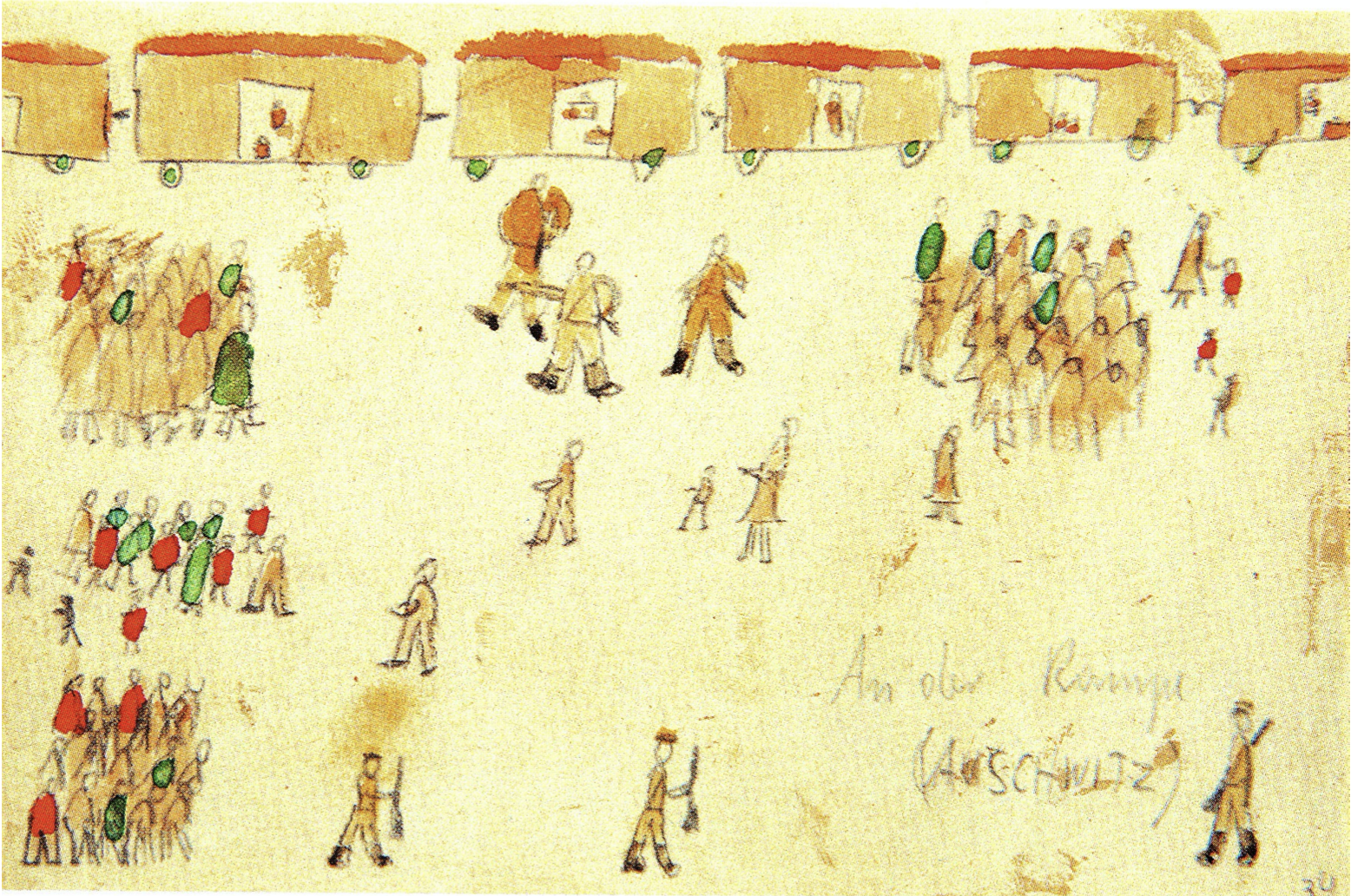

So that was the context of how Thomas came to be in Zug. I lived in Zug for six-and-a-half years, so we had a rather loose connection, but I was really interested when I saw one of Thomas’s drawings in this little leaflet. I reached out through good old Google to find out more about the name Thomas Geve. I saw a lot of his drawings; they were very powerful drawings for me, because they were through the eyes of a child, through the eyes of a 15-year-old. And, obviously, some of these drawings are quite well-known, quite renowned. I was just really interested to find out more. He drew over 80 drawings; we’re not exactly sure how many, but certainly over 80 drawings when he was liberated.

I introduced myself to his daughter through his website. We started talking on the phone, and we got on very, very well. I learned a lot more about Thomas and his life and the fact that he had already written two books about his experiences, and it literally started from there. It was a completely random circumstance. It has nothing else to do with my background. I’m not a historian; I’m not an expert. I’m not Jewish.

What was your connection like?

We got on very well. In early April 2019, I introduced myself. His daughter Yifat and I got on the telephone. We spoke through April, and I ordered his book “Guns and Barbed Wire.” It hit me how powerful I felt his testimony was. He’s lived a remarkable life, let alone the life he led before he ended up in Auschwitz Birkenau. He escaped and evaded the Gestapo, the German police, the SS, for years in Berlin with his mother before he entered at the age of 13. It’s an extraordinary story. I was bowled over by his account and thought it would be amazing to be able to potentially bring it to today’s audiences. There was no publisher lined up.

I said, “I’m going to book some flights, and I’m going to come out to Israel and see you,” to try and talk through his experiences and see his drawings firsthand, which was an immense privilege—his drawings are held under lock and key at Yad Vashem’s Museum of Holocaust Art in Jerusalem.

I spent a week with him and his family in Tel Aviv. We found out new details, which was secretly what I was hoping for, because if it was just a question of reprinting, you know, that’s quite an easy job. This was more to update it and bring it to today’s audiences. Thomas’s first language is German; he’s got exceptionally good English, but his first language is German. I felt that the structure needed to be improved—basically I was wearing a number of different hats to try and make this an easier read.

Thankfully, the proposal was approved by HarperCollins toward the end of 2019. And then we really had four or five months plus COVID to submit before it was published in 2021. It was a real roller coaster. In America, it was launched on July 27, and then we’ve got six or seven country launches coming up over the next six to 12 months.

Ours is the third updated edition of his testimony. In the 1950s, he wrote a book called “Youth in Chains.” In 1987, he wrote “Guns and Barbed Wire.” As you can tell, the ’50s audience is different from the ’80s audience, and this updated edition is going to be very different. That was one of the aims, to bring it to today’s audiences with some of his drawings. We have 56 of his drawings in the book.

What is your goal for the readership?

I think it’s educating all generations through Thomas’s story, to make them aware of what happened but also to make them aware of how to stop it happening again, which I think is the same goal a lot of people have when they’ve done memoirs on the Holocaust: to teach people and educate people through their own experiences. And, certainly from Thomas’s perspective and the family’s perspective, it is to educate future generations and today’s generation.

I think there are some other potential themes here: the fact that he was 13 when he entered into the Nazi concentration camps and then was liberated at age 15—this is through the eyes of a child. His drawings are almost brutally simple. But, therefore, they’re much easier to take in and to understand. I found his drawings incredibly powerful. So I think there’s the education awareness perspective of his story, but then you’ve got the drawings to tell that story as well, which I think is quite unique.

Why is this book so important now?

There is the threat of not just antisemitism but the general threats across society. With COVID, Thomas’s generation is going to be gone very soon. Thomas is relatively young; he was 15 when he was liberated. When, sadly, people like Thomas do pass on, you lose that human connection, that human link to this notorious event.

I think every Holocaust memoir is unique. Every Holocaust memoir is different. Learning about this infamous event in history through someone like Thomas is a way of getting better education and understanding of the Holocaust and what happened, because in a few years’ time, you will lose that human link. And it’s very difficult to see something like this on TV or in a magazine or a book when there is no one there to be the face of it. The other side is that it’s relatively unique to have a testimony, which is both in illustration and in text; it’s very rare. I think of the expression, “Every picture tells a thousand words.” These visuals are very important.