Earlier this week, overlooking the mountains between Ethiopia and Sudan, I heard the extraordinary story of a Jewish family’s life-risking journey on foot through those same mountains. Retelling her family’s story, Sigal Kanatopsky, Jewish Agency for Israel (JAFI) leader and shlicha (emissary) to the U.S., described traveling through the night with elderly people and children, and no knowledge of if, or when, they would make it to Israel. This was one of the poignant stories I heard this week during my first mission to Ethiopia to learn about Ethiopian Jewry and travel with the first flight of what will be 3,000 new Ethiopian olim (immigrants) to Israel.

The story of Ethiopian Jewry has been compared to a modern-day Exodus. When Sigal described the unexpected knock on their door one night telling them to get ready to go to Israel immediately, it sounded like a literal yetziat mitzrayim (exodus from Egypt). Like the Israelites whose bread did not have time to rise, her family didn’t even have time to eat the food that was on their table. Their journey took them from Ethiopia to Sudan, where they would wait six months in a refugee camp before being rescued and flown to Israel in the middle of the night.

“Their passion, vision, and longing to return to Jerusalem was so strong that when they learned of a modern State of Israel and the possibility of return, it was simply not a question of if, but rather how,” Sigal explained. “They just started walking.”

For thousands of years, Jews known as Beta Yisrael lived in Ethiopia, kept Jewish traditions, and longed with a fervent passion to return to their beloved Jerusalem. From 1983–1991, including two historic operations, Moses and Solomon, the Israeli government and military brought approximately 57,000 Ethiopians to Israel under the Law of Return. Over the past decades, additional Ethiopian aliyot have reunited families and fulfilled the dreams of thousands more Ethiopians—like Sigal’s—who have continued to live Jewish lives and longed to move to Israel.

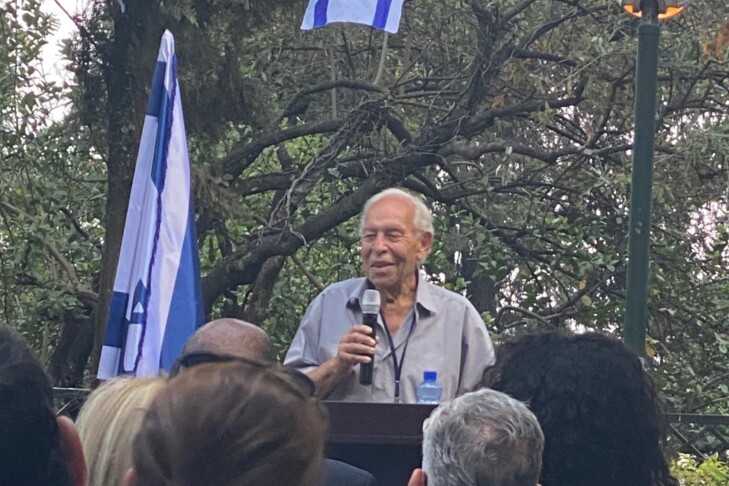

At the Israel Embassy in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Micha Feldman, a living hero of the history of Ethiopian Jewry, shared with us his personal experience of Operation Solomon in 1991. After a dramatic, hour-by-hour recount of the operation and its success, Micha reflected on his personal story and what his work with Ethiopian Jewry meant to him as an Israeli and child of Holocaust survivors. Three weeks after Operation Solomon, while on a trip to Munich, Germany, to meet with the Jewish community there, he visited the Dachau concentration camp. He recounted:

“There in Dachau it hit us. We understood the significance [of the rescue of the Ethiopian Jews], not just for the Jews who returned to Israel, but for us, the ones who helped them to get there. Standing in front of the crematorium at Dachau, I said to myself, ‘Everyone is thanking you, but you should thank them.’ The Ethiopian Jews who, on their initiative, went to Sudan in the ‘80s and came to Addis Ababa in the ‘90s made it possible for us to help them fulfill their dream… They are the real Zionists of our time.”

Micha’s words reminded me of something former CJP president Barry Shrage wrote in 2006 after he returned from a similar mission to Ethiopia:

“Jewish history seems always balanced between victory and defeat, celebration and mourning, miracle and catastrophe. But always, for me, in the background, is an unseen hand that guides us to an unknown future, but that demands our participation….”

People have asked me why I chose to go on this mission, and my honest answer is that I couldn’t not go. The unfolding story of Ethiopian Jewry and the broader story of collective Jewish responsibility in the 21st century simply “demand my—and our—participation.”

Perhaps it is coincidental that this mission took place in the week leading up to Shavuot, the Jewish holiday that commemorates the receiving of the Torah at Mount Sinai and the culmination of a period of wandering, a journey that began 49 days earlier on Passover. We are reminded that our memory of slavery and the liberation from it is meant to inspire in us the acceptance of the ethical and spiritual responsibilities that define our covenantal community. We are not victims of history, but rather actors and initiators, engaged participants and writers.

The world can change in a heartbeat, and we need to be ready when history calls us. When it does, the collective power and impact of the global Jewish community far outweigh what any of us could achieve alone. It was so inspiring to see this firsthand this week.