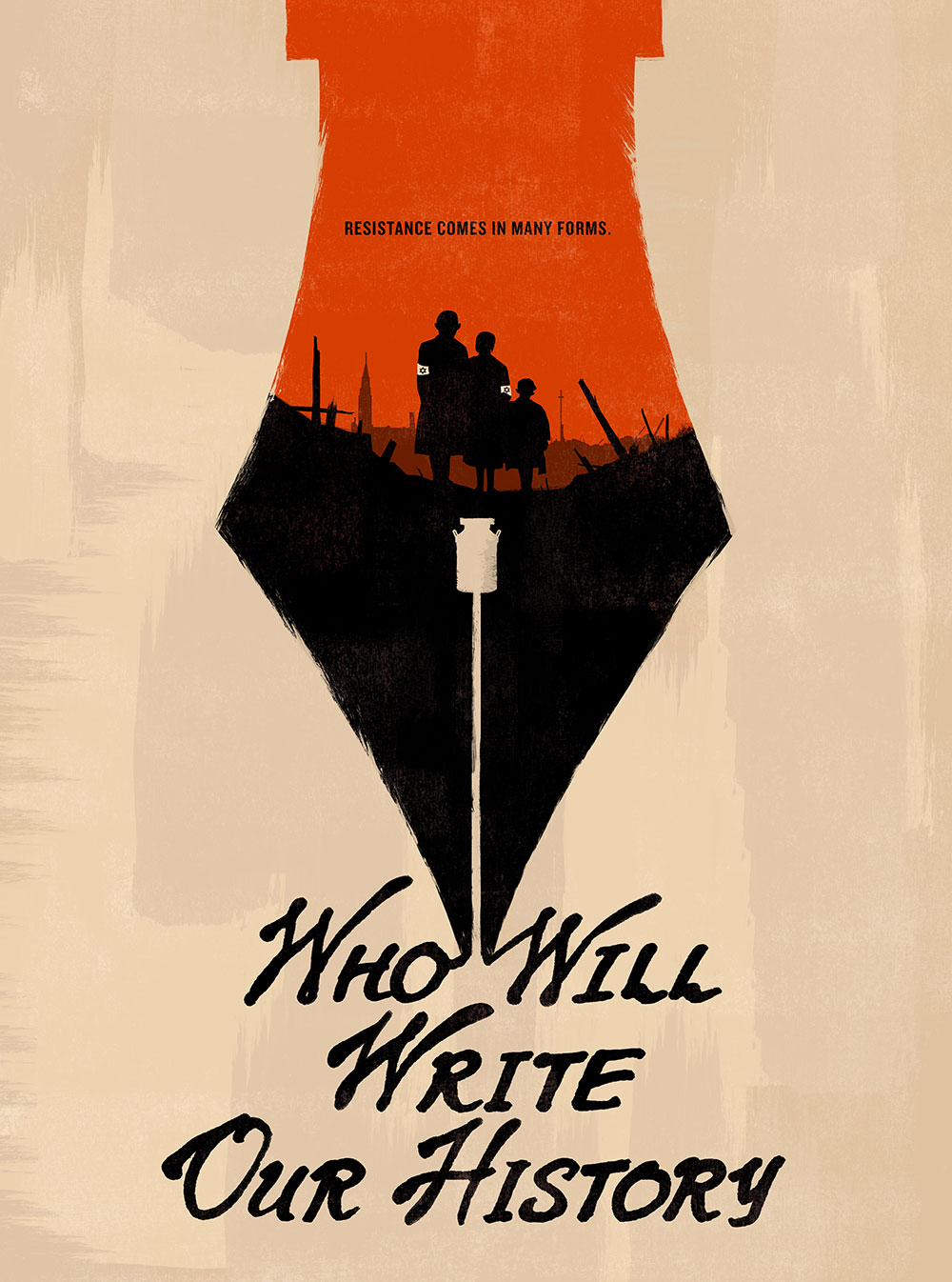

Roberta Grossman, director of the docudrama “Who Will Write Our History?” frequently quotes an entry in a diary found in the Krakow ghetto after the Holocaust: “We fight for two lines in history to let people know we were here; we did something.” Grossman was on hand last week to introduce a special presentation of her film at Coolidge Corner Theatre. “I’ve taken the visions and dreams of the people in the ghetto,” noted Grossman, “and turned them into a film.” Grossman and Jan Darsa of Facing History and Ourselves were in conversation about the film and answered multiple questions from the audience.

Grossman described “Who Will Write Our History?” as a hybrid between a feature film and documentary. It is a work that gives heed to a courageous band of men and women in the Warsaw Ghetto who resisted the Germans in word and deed. Their leader was Emanuel Ringelblum, a historian who was determined to tell the world what was happening to the Jews of Poland during World War II by amassing secret archives of the Warsaw Ghetto.

The film is based on historian Samuel D. Kassow’s book of the same name. “Sam discovered the story,” noted Grossman. “He was born in a DP camp and became a professor of Russian history who grew up among survivors in Hartford, Connecticut. He frequently says that nobody in his group of friends had grandparents. He deliberately did not want to engage with the Holocaust as a historian. But he bumped up against Ringelblum and discovered they were kindred spirits. The book is a work of historical rescue.”

Using the code words Oyneg Shabbos—Yiddish for “the joy of the Sabbath”—Ringelblum assembled a team of 60 women and men to document daily life in the ghetto. He based his archives on the model of the YIVO Collection, which started in Vilna in the 1920s. The YIVO Collection told Jewish history based on the memories and observations of ordinary people, rather than focusing on the Jewish intelligentsia. The egalitarian spirit of the YIVO Collection appealed to Ringelblum. “Ringelblum tried to tell the story [of life in the Ghetto] from many points of view, including children, religious persons and secular persons,” Grossman said. “The archive is a very sophisticated research institute in the depths of hell. Ringelblum imposed standards like the historian that he was.”

Each person who was part of the Oyneg Shabbos contingent was given a notebook and a small stipend for their efforts, and they contributed to the Oyneg Shabbos archives on penalty of death. Over the course of a couple of years, the group collected over 60,000 pages of documentation that included writings, artifacts, artwork, notices posted in the ghetto, music, photographs and poems. Over time, the archives refuted Nazi propaganda and their anti-Semitic caricatures. “Most of the images on film that were left behind were images from the Nazis,” said Grossman. “Emanuel Ringelblum felt it was important to counter that narrative with Jewish writing and artifacts.”

The Oyneg Shabbos archives were eventually buried in three separate locations in the ghetto. Only three people knew where the archives were hidden, and only one of those people survived to help unearth the documents. After the war, locating the archives was a herculean effort. After the Soviets liberated Warsaw, the ghetto and its environs were reduced to rubble. Workers had to consult a prewar aerial map to locate two of the three caches. The third cache is believed to be located under what is now the Chinese embassy.

In the film, Grossman brings together historical footage with reenactments set in the ghetto. She frames the story from Rachel Auerbach’s point of view. Auerbach was a Polish-Jewish journalist, who Ringelblum convinced to run one of the ghetto’s 100 soup kitchens. As voiced by Joan Allen, Auerbach’s insights are powerful and affecting. At one point, the film recreates Auerbach’s walk through the ruins of the ghetto. What initially appears to be a snowstorm are feathers from destroyed bedding.

The words that Auerbach and other actors speak in the film are taken directly from the Oyneg Shabbos entries. Auerbach wrote in her diary: “Oh, the crying of things abandoned forever by their owners, becoming degraded in strange hands like corpses not buried who have no one to do right by them. He who has not seen the weeping of dead things, he has not seen or heard in his life any sad things.”

After the war, Auerbach immigrated to Israel and founded the Survivors Testimony Department at Yad Vashem. She was pivotal in convincing prosecutors at the Adolf Eichmann trial to enter survivor testimony as crucial evidence.

Today, many of the surviving Oyneg Shabbos materials have been restored and curated in the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw. The institute is housed in one of the few buildings that were left standing in the ghetto. In 1999, the archives were among the three collections—the other two are Frédéric Chopin’s masterpieces and Nicolaus Copernicus’ scientific writings—from Poland included in UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register.

As Grossman writes in her director’s notes, “On the eve of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Oyneg Shabbos members buried 60,000 pages of documentation in the ground in the hopes that the archive would survive, even if they did not, to ‘scream the truth to the world.’”

Find upcoming film screenings here.