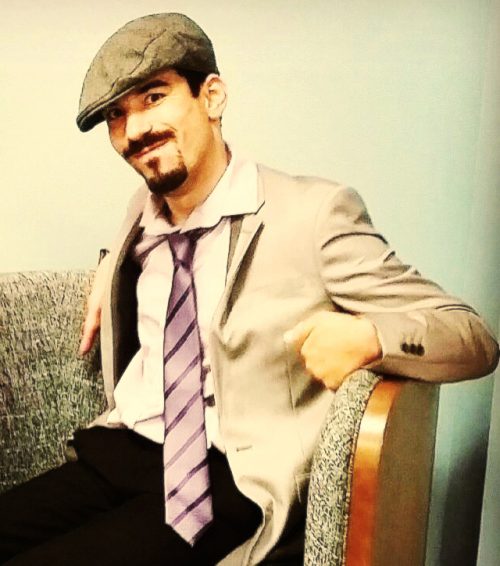

At first, it seems it will be difficult to converse with filmmaker Alexander Freeman, that his speech constrains him. Freeman has cerebral palsy, and it affects the way he talks. But if you lean into the cadence of his words, his eloquence soon emerges.

Freeman acknowledges that it takes him longer than most people to get a thought across. It hasn’t stopped him from directing an award-winning film and brilliantly riffing with JewishBoston about his work.

Freeman’s latest documentary, “The Wounds We Cannot See,” carries the subtitle “One Woman Struggles to Live One Day at a Time.” The film’s subject is Nancy Ross, a former U.S. Navy airman who was raped in the late 1980s during her tenure of service. Ross has struggled with anxiety, depression, addiction and other mental health issues before and after her trauma. The film, which debuted in 2016, has garnered a bevy of awards—11 so far.

“The film is one person’s experience, but it is also everyone’s story,” according to Freeman.

I, too, am no stranger to depression and anxiety. I was deeply impressed by how Freeman accurately portrays such illnesses as hidden disabilities; that is certainly my experience of them. Freeman says he hopes the film will show that not only are Ross’ addiction and mental illness not a choice, but they are also very much a part of who she is.

These days I feel well much of the time, thanks to the miracle of psychopharmacology, but my struggle with these illnesses has shaped who I am as a woman, a wife and a mother. For better or worse, it permeates my relationships and often defines them. I am blessed that most of the people in my life have opened their hearts to me. “Oftentimes, I see people disregard someone because they have a disability,” says Freeman. “That’s really not the correct reaction.”

Before making “The Wounds We Cannot See,” Freeman made a highly personal film called “The Last Taboo.” The film focuses on six couples in which one partner has a physical disability and the other is able-bodied. It’s a realistic film that manages to be both thought-provoking and warm-hearted, and in which Freeman addresses and even upends notions of identity, sexuality, gender and beauty. Universities and nonprofits have recognized the trailblazing film by using it as a teaching tool. As Freeman said in a 2013 interview with ABC, “If we are denied our right to sensuality, we are denied being human.”

Capturing a person’s essential humanity is a running theme for Freeman. In less than 90 minutes he conveys the complexities of Ross’ humanity by simply training his camera on her and allowing her to talk. “Nancy’s moods could be very unpredictable,” he recalls, “so we never knew what challenge she was going through. I would call her, and it might be an on or off day. It was difficult. I was always learning something new about her. There would always be some new fact, some new thing that happened to her, and that was key to the story arc and to editing the story.”

Freeman and his crew shot the principal interview for “The Wounds We Cannot See” over the course of two intense days in January and February on Cape Cod, where Ross lives. It was the winter of 2015, one of the worst on record in Massachusetts, but Freeman and his crew still shot 30 hours of footage, continuing filming b-roll of Nancy in March and again in August 2015. “We had hours and hours of it to go through,” he says. “My editor and I went through everything and created a whole story. Over the course of 2016, we cut a lot of the repetition to make the film as faithful as possible. It took hours and hours and months and months of work to make this film, but I wanted it to feel as if we shot it in one breath.”

Freeman is seeking investors for his next documentary, “Castable,” which takes on the Hollywood machine. As Freeman describes it, it’s “an inside look at the lack of employment opportunities and misrepresentation of people with disabilities in the entertainment industry and beyond, but also what needs to change.” Academy Award winner Chris Cooper narrates the documentary.

While Freeman is passionate about giving marginalized people voice in his films, he is equally adamant about communicating “that no one has to stay the way they were before. They can always get better if the help and acceptance is there.”

Freeman and Ross are living proof of that observation. And so am I.

“The Wounds We Cannot See,” produced by Outcast Productions, is distributed by Indie Rights Movies and can be viewed on Amazon Video, Google Play, YouTube Red, iTunes and Vudu.