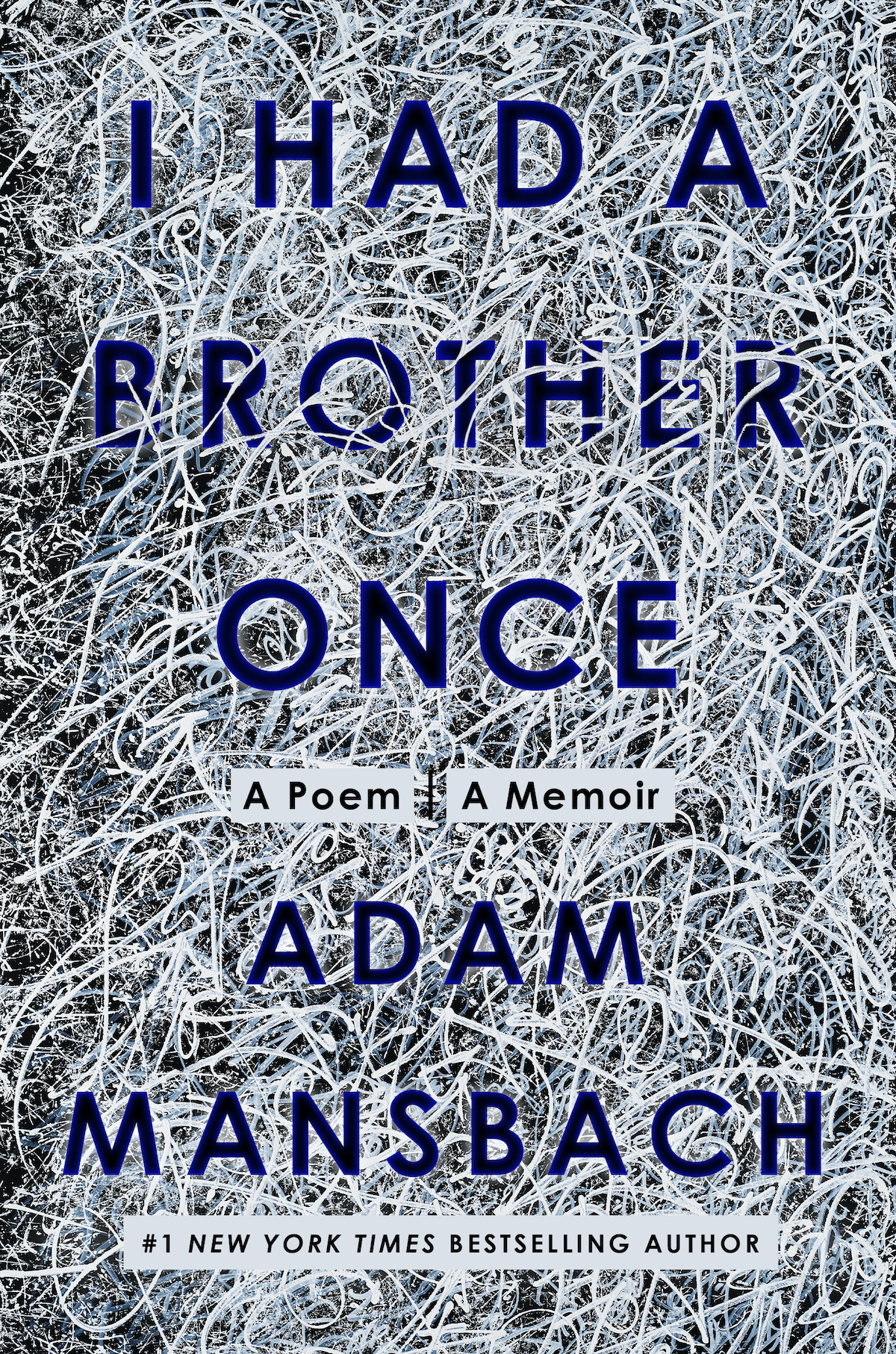

Adam Mansbach, a novelist, humorist and poet, has recently published a deeply affecting memoir in verse about his brother. “I Had a Brother Once” is the story of David Mansbach’s suicide a decade ago. Mansbach is also the author of the surprise bestseller “Go the F*** to Sleep,” and David’s death by suicide happened on the cusp of Mansbach’s viral book tour.

The Newton native recently spoke to JewishBoston about his grief and disorientation immediately after David died, rediscovering Jewish ritual and how writing the book in a short, intense burst eventually brought him peace.

You were at the beginning of an extensive media tour for “Go the F*** to Sleep” when your dad called with the terrible news of David’s death. What sort of double life did that create for you?

It created a very strange and intense double life. I was balancing this public performance of joy and unexpected success in this incredibly public manner. I was on television and doing interviews literally every day for the next year as I dealt with this private shock and grief. To further complicate things, there was this sense that just as my brother had worn a mask to disguise what was really going on with him, I was now wearing a dissimilar mask, but a mask nonetheless. I was traveling the country and doing media across the world and being, if not dishonest, then certainly less than truthful about my life. I had this persistent sense of compounding my grief by not talking about it, by publicly hiding it.

David died 10 years ago. Did it take you this long to sort out your grief to be able to write “I Had a Brother Once”?

It took me eight years. I wrote the book two years ago. I started it around the time of what would have been David’s 40th birthday in late April. It only took me three weeks to write the book. But in some sense, it also took me eight years and three weeks to write the book. I never stopped contemplating how I might write about my brother. I’m a novelist by training, and so I spent a long time trying to think of what a novel might look like. But the architecture and the scaffolding of a project like that always stopped me before I started. The same thing happened when I thought about it as a long-form essay, or a screenplay.

How did you decide poetry was the right genre to tell David’s story?

Two years ago, I was commissioned to write a piece for an event at SFJAZZ Center. A bunch of poets were performing with a live band, which put me in mind of poetry. I also wrote an elegy for a musician who had recently died, and I performed it with the band that week. That week of performance reminded me of the power of poetry and the simplicity of it. The lack of scaffolding, the lack of elaborate architecture, the way that you can move very quickly in poetry—move from idea to idea and scene to scene, and make connections simply through proximity, as a friend likes to say. As soon as I came home from San Francisco, I began to write, and the book ended up as one long poem. It was a very intense and ultimately very fast process of writing. Some of it was about getting down on paper things that I had always known and thought. But I also made a lot of connections on the page that I had not made until I sat down to write.

Were you surprised that it took you just three weeks to write the book?

It was a writing process unlike any other; it was very intuitive. I didn’t always know why I was bringing something in or how it would connect. But I trusted the impulse, and it always connected in a way that was often unexpected but that always made sense to me. I didn’t have an outline or road map, so every day I wrote until I had to stop. Part of me wanted the writing to keep going, and part of me was desperate for it to end because it was such an emotionally intense and grueling process.

What was the hardest thing for you to face on the page?

That’s a good question. So much of this was hard to face on the page. There are parts of the book where the attempts to write about who my brother was—not about his death, not about my own experiences, not about my wrestling with narrative or paradox—but just trying to render something of who he was in a way that felt accurate, honest and fair without being overly elegiac or charitable. He was a wonderful guy and thoughtful guy, but also a deeply weird guy who I loved but couldn’t always connect with.

After David died, you found the receipt for the chemicals he used to die by suicide. But you also found he ordered an expensive skateboard around the same time. How did that paradox affect you?

Understanding paradox as something that you don’t try to resolve, but you can merely sort of hold and look at, has been part of the grieving process for me. It’s understanding that it isn’t some kind of “aha moment” as in a detective movie where everything is called into question and suggests foul play. A depressed person can simultaneously plan to live and skateboard, and also plan to die. That’s never going to be resolved. And it’s not going to do anybody any good to try to resolve it.

You mention the Mourner’s Kaddish at the end of the book. Did you discover or rediscover any rituals that helped you cope with your grief?

In the moment, the Kaddish meant everything. Not because I speak Hebrew, not because I understand it and not because I come from a family that, for the most part, is hostile toward organized religion. Yet my family is deeply Jewish. If you asked my father to describe himself in five words, he would absolutely say that he is Jewish, as would have my grandfather and my grandmother. But if you suggested to any of them that they go to a synagogue, even for a bar mitzvah, they would refuse.

But I found myself wishing I had more ritual, wishing I had a less fraught relationship to some of the rituals. We performed certain rituals after David died and felt as if we were doing them wrong. I say in the book something like, “We were sitting shiva but felt we didn’t know how to do it. Instead of covering the mirrors, we became them.” We sat in the house staring at each other and crying for a couple of weeks. So that moment of Kaddish is very powerful because you don’t need to know the words to understand the history. The fact that this prayer has been recited for millions of people over thousands of years is also very powerful.

How has your relationship to ritual evolved since David’s death?

I spend a lot of time thinking about ritual and wondering how to access it, wondering if one could, in fact, invent ritual, or if that disqualifies it from being a ritual. There’s a lot that I treasure and hold very dear about Judaism, and high on that list is the notion of inquiry—the idea of constantly searching and seeking and asking questions that have no answers. This sense of probing and thinking in community with others and alone is critical. And in some ways, this book reflects that.

Find resources for suicide prevention at Samaritans and the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.