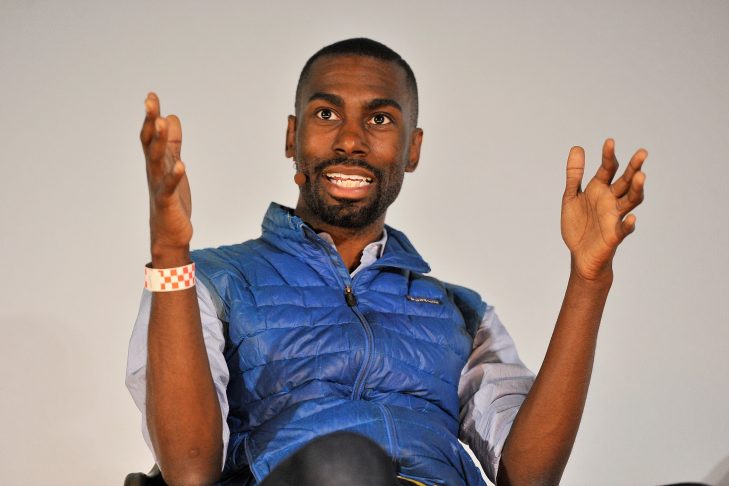

DeRay Mckesson is chiefly known for two things: his Black Lives Matter activism and his trademark blue Patagonia down vest, which he always wears. It’s a security blanket of sorts, and he had it on when he met President Obama, Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders and Beyoncé. For the past four years Mckesson has crisscrossed the country protesting police brutality and talking about the 2014 protests against police violence in Ferguson, Missouri.

The former teacher came to attention for live-tweeting his 400 days in the streets of Ferguson. In his new memoir, “On the Other Side of Freedom: The Case for Hope,” Mckesson asserts, “Twitter was an important vehicle because it amplified the work on the ground and allows us to be truth tellers about our experience.” A few pages later, he writes, “It was on Twitter that we learned to fight erasure. In protest, we became the unerased.”

In the summer of 2014, Mckesson, who was based in Minneapolis at the time, drove to Ferguson with the intention of staying for only a few days. He stayed for over a year. In the midst of pepper spray, smoke grenades and rubber bullets, he witnessed the strength of the protestors and the consequences of civil disobedience. In the book he writes of the five-second rule implemented by police in Ferguson. The rule meant that no one could stand still in the streets for more than five seconds. This meant no sit-ins and no cohesive protests. A few months later a federal judge deemed the rule unconstitutional.

During his time on the streets, Mckesson came to understand that “protest at its core is telling the truth.” Running through that core of protest are two things: faith and hope. He writes: “Faith is the belief that certain outcomes will happen and hope the belief that certain outcomes can happen. Faith is rooted in certainty; hope is rooted in possibility—and both require their own kinds of work.” For Mckesson, faith and hope are constants in his work.

In the book, Mckesson seamlessly moves back and forth in time to reflect on the experiences that made him the man he is today. His mother was addicted to drugs and left him when he was 3 years old. His father, Calvin, was a single parent to Mckesson and his sister, TeRay. Activism was in Mckesson’s blood from an early age; as a teenager he was a community organizer in his hometown of Baltimore.

From there, Mckesson went to Bowdoin College, and after graduation worked in education as both a teacher and administrator. He came out as a gay man when he was a teenager. In writing about his sexuality, he equates the metaphor of living in the closet to existing in the quiet. He writes: “If your love requires that I hide parts of who I am, then you don’t love me. Love is never a request for silence.”

Among the significant contributions from Mckesson and his colleagues are the creation of Mapping Police Violence, a comprehensive, data-driven study of police killings in 100 of America’s largest cities. Among the study’s findings is the astonishing fact that in nearly 100 percent of cases, officers who were involved in fatally shooting a black person were never criminally charged.

The heart of Mckesson’s book is a passionate, tough critique of policing in America. He observes that the police “primarily wield negative power—that is, they take away to purportedly give. They seize, detain, arrest, imprison and kill to maintain law and order in society, in order to manage conflict.” He calls on his fellow activists to challenge the institution of policing—maintaining the status quo is too high a price to pay.

He details three reasons that policing has not been successfully confronted: “… [T]he first is that people think that the absence of police being indicted, convicted or fired for occurrences of police violence means that no wrongdoing took place, and therefore no changes are necessary; the second, they believe that communities have so much conflict and that consequently policing is such a hard job that they accept instances of police violence as the cost of doing business; and last, people literally cannot imagine a way of managing conflict that is not rooted in negative power, the main style of policing.”

Mckesson ends his book on a note of hope and urgency in a letter he drafts to a young activist. He says: “You do not stand in the shadow of those who fought before you; you stand in their glow.” In his letter he advises young activists to be patient. Change may not come quickly, but it will come. For Mckesson, it always comes down to faith and hope—“to actively surrender to forces unseen, to acknowledge that what is desired will come about, but by means that you may never know, and this is difficult.”