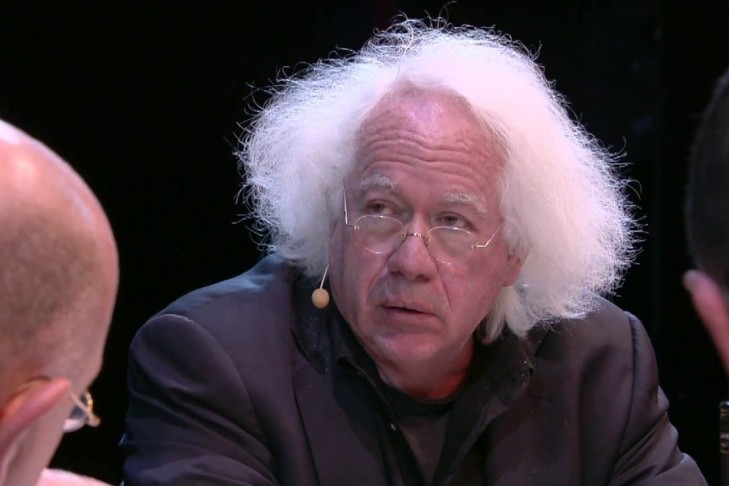

Leon Wieseltier, the 13th speaker to deliver the Connie Spear Birnbaum Memorial Lecture, brought good news and bad news about the state of American Jewry to Boston. Sponsored by the Synagogue Council of Massachusetts, Wieseltier spoke this past Sunday to an audience of approximately 500 people in the sanctuary of Congregation Mishkan Tefila in Chestnut Hill.

Wieseltier is one of the foremost thinkers on American and world Jewry. As the literary editor of The New Republic from 1983 to 2014, he wrote regularly about Israeli current affairs and issues of Jewish identity in his influential “Washington Diarist” column. He is the author of “Kaddish,” winner of a National Jewish Book Award and the recipient of Israel’s prestigious Dan David Prize in 2013. He is currently the Isaiah Berlin Senior Fellow in Culture and Policy at the Brookings Institution and a contributing editor at The Atlantic.

Wieseltier opened his talk by pointing out that the experience of American Jewry has been nothing short of a revolution in U.S. history, as well as world history. “The good news that I bring to you,” he declared, “is that we are philosophically and politically secure here.” Engaging and erudite throughout his 45-minute speech, Wieseltier was not so much lecturing as he was teaching. He patiently and eloquently took his audience through various eras of Jewish history to contextualize the Jewish-American experience.

Unlike fellow Jews in Europe, he discerned for his audience that, “in the United States, the rights of the people are axiomatically given, and the Jewish community has learned that here we do not have to argue for our rights and we may openly argue for our interests.” To hone his point, Wieseltier noted that a group like AIPAC would be “inconceivable” in Europe. And while anti-Semitism exists all over the world, the moral and social costs of indulging in it are very high in America. “It is safe to say,” noted Wieseltier, “that anti-Semitism in this country is not just wrong; it is not legitimate.”

Weiseltier spent most of his talk delivering his bad news—news that reported that more of the Jewish experience is “slipping through our fingers in these conditions of security and prosperity than we ever lost in any condition of poverty and pressure.” With unprecedented security for Jews in the United States comes a corresponding Jewishness that Wieseltier described as “thin and lousy.”

According to Wieseltier, American Jews have chosen the easier perks of ethnicity over the hard work of cultivating a core identity. We have confused culture with learning. “If you regard all expressions of identity anthropologically and sociologically, then they are all equally authentic and equally valid. Every culture has to have an internal hierarchy of values,” he said.

While Wieseltier occasionally veered toward the scholarly—for example, he cited “Beyond the Melting Pot,” the influential 1963 book by Nathan Glazer and Daniel P. Moynihan on the development of minority groups in New York City, to explain how Jews redefined themselves as an ethnic group—he was consistently accessible. “We gained with other groups the holy hyphen,” he said. And thus, according to Wieseltier, the modern Jewish-American was born.

But perhaps the most dangerous problem for American Jewry since the 1960s is its illiteracy about all things Jewish. It is, Wieseltier stated, “a breathtaking community-wide irresponsibility not to know Hebrew.” In a striking allusion to Psalm 137, Wieseltier asserted: “Our right hand is losing its cunning because we have forgotten something even greater than Jerusalem—we have forgotten our letters and our words. We are full of speech and yet we are mute.” Consequently, Wieseltier asked the following tough questions about our disconnect from Jewish language and tradition, and our ability to perpetuate Jewish tradition: How does what we have created compare to what we have inherited? Did we add to our tradition or subtract from it? Did we transmit it or did we let it fall away? Did we enrich it or did we deplete it? Among the great Jewries, what is our distinction?

During his Boston appearance, Wieseltier was as much a prophet as he was an intellectual. It turns out that despite the red, white and blue glory of American Jewry, “the holy hyphen” between “Jewish” and “American” can also be a vibrating tightrope. Although Wieseltier did not use the word assimilation—it would have been too facile a conclusion—the heavy price American Jewry is paying for it was implied in Wieseltier’s clear-eyed and impressive presentation.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE