A nigun, a wordless song with prayerful undertones, is perhaps one of the most accessible of Jewish spiritual expressions. Sung anywhere Jews gather, a nigun can spontaneously happen in places as formal as the synagogue or as informal as the Shabbat table. Distinctive and repetitive sounds like “bim bim bam” or “nai nai nai” are hallmarks of the nigun.

A new exhibit at The Gallery @ Mayyim Hayyim, called “Nigun | Notations on Prayer,” gathers three printmakers’ visual responses to the ubiquitous nigun. Emily Mogavero, an artist in the show who is also its curator, noted: “Nigunim are ‘shape shifters.’ The show’s printmakers put forward the responsiveness, the repetition and the rhythmic aspects of these wordless melodies. Their prints have all these elements of the song and its layers coming together.”

Mogavero, along with the other printmakers in the show—Shelby Feltoon and Stacy Friedman—spoke to JewishBoston about the influence of the nigun and the creative process it inspired in their work.

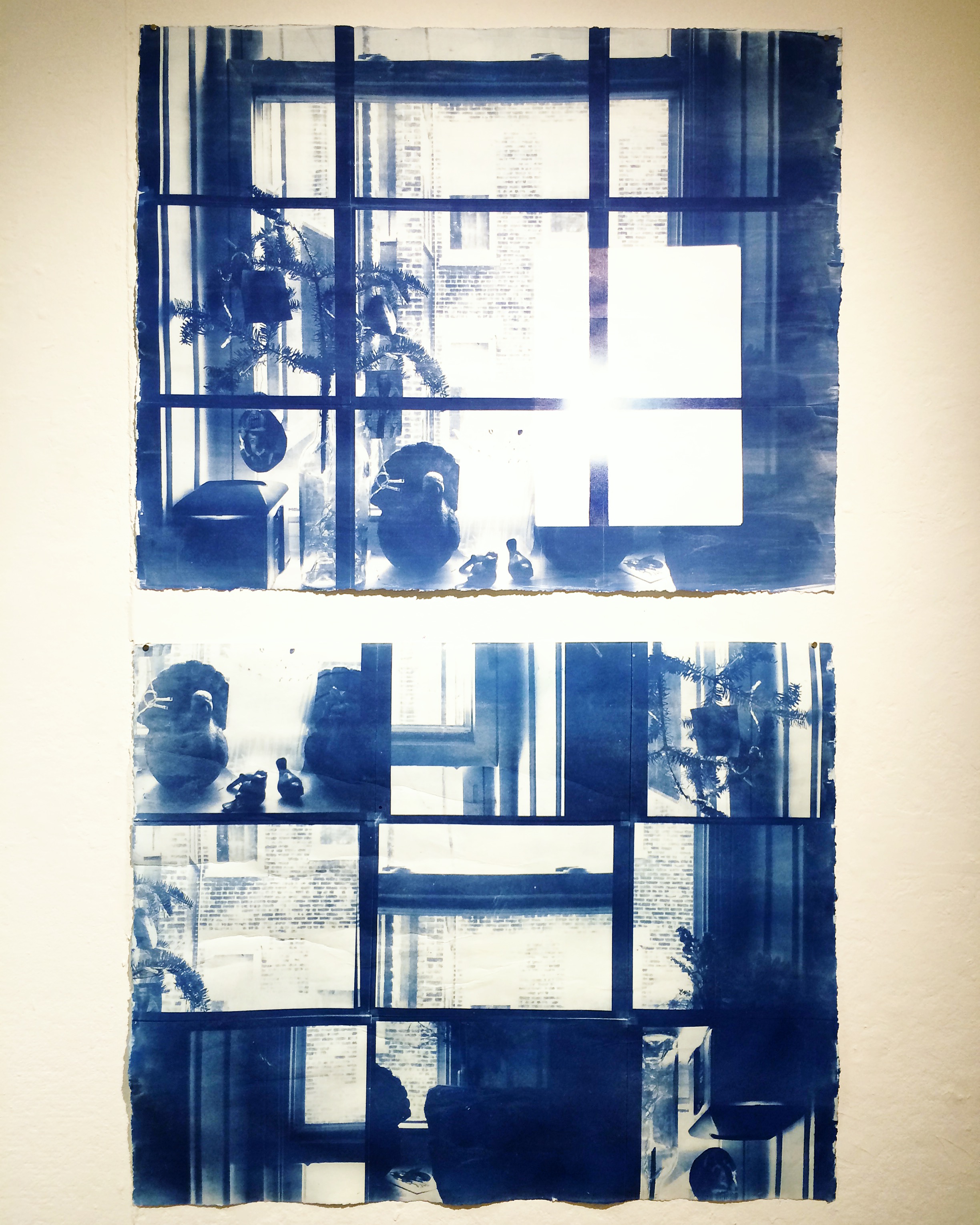

Shelby Feltoon

“My work in the exhibition is from a series called ‘Retrieval.’ The word ‘retrieval’ in relation to the series reflects on the cognitive process of memory. Memory goes from acquisition to retention to the retrieval of information. Sometimes retrieval [of memories] is the hardest part, depending on how the memories are coded and how much emotional residue is tied into them.

“My pieces evoke personal memories that can also be universal and collective. Even if we try hard to make a memory last, it can still be muddied and harder to retrieve. I show that by combining different images, confusing them through repetition. The viewer wants to make sense of the images, but in the end, they don’t resolve. That repetition is in a gray area of wordlessness that ends up relating to the nigun.

“Most of my work in the show consists of pieces of retrieval that play with the element of memory. A couple of pieces resemble windowpanes and blueprints. They evoke piecing together memory by repeating a process over and over and varying the outcome by using the same sets of limitations. My smaller monoprints relate to creating melodies and capturing this cadence. I tried different things to create a baseline set of rules for an underlying melody; it’s the basis for improvisation.

“So much of printmaking is about taking a subset of rules and elaborating on those rules. Nigunim build over time in the same way. As people are singing together, they elaborate and improvise.”

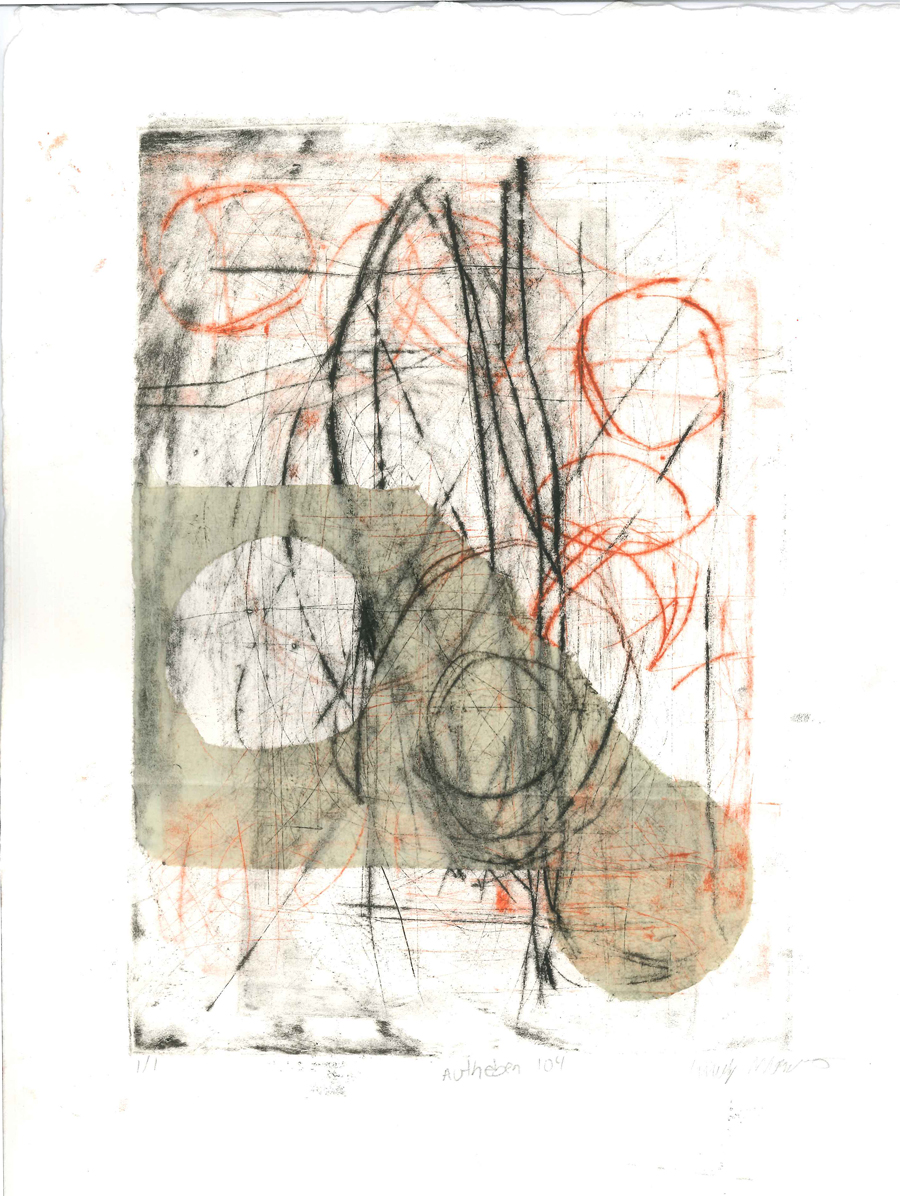

Emily Mogavero

“Printmaking is a very responsive and collaborative process. Most printmakers work in a print shop and share the press with other people. There is also collaboration between a printmaker and the press. Surprising things happen and have to be responded to. All of the artists in the show are making abstraction from life.

“Since graduating from college, I’ve explored two different paths. One is based in art history—I repaint images of women by male artists. The work parallels my education and my role at the Institute for Contemporary Art. As an artist and an art historian, I am critical of history as a construct. My work uses printmaking as both a process and a conceptual framework. Within that framework, I explore the creation and destruction of images and the rewriting of history.

“In my ‘Aufheben’ series—a word that means both destroy and preserve—I’m rewriting and cataloguing my own marks on the plates and making a history of that in the print. I erase and redraw, and there is this record of that on the plate while the history of each mark is in each subsequent print. It’s an act of preserving and destroying. Going back to edit, rewrite and remember.

“There is an element of the nigun in my work displayed in the show. With printmaking and nigunim, there is a communal aspect. Nigunim are always part of a community.

“The printmaking process for me is spiritual and prayerful. The spontaneity and repetition of the process—continually sanding, inking and wiping—enable me to get out of my head to feel fully present and connected. It’s meditative. I’m communicating with the universe through shapes, lines, colors and actions, instead of words.”

Stacy Friedman

“All of my recent work—especially the pieces in the Mayyim Hayyim exhibit—is monotypes. In them, I’m thinking about family history, lineage and memory. In school, I was always interested in people. I have done more traditional portraiture, but in my newer work, I’m looking at family photos and thinking about the people in them. In connection with this work, I researched my family history and archived old family photographs. The figures in those photographs show up in my prints as silhouettes while remaining anonymous. I’m attempting to evoke their stories and their immigrant journeys.

“In my new prints, I incorporate actual photographs. As with the silhouettes I have used, viewers can come to the work and think about their family. They don’t have to know who these people are. People can bring their own identities to these anonymous figures.

“When I made the work currently showing at Mayyim Hayyim, I was thinking about the idea of the Jewish community. I focused on the repetition of form and shape. Consequently, the silhouettes speak to the repetition in the songs and melodies of nigunim. I feel strongly that these figures are part of the Jewish community, as well as the story of that community. Therefore, having this work displayed in a Jewish space is especially relevant.”

The Gallery @ Mayyim Hayyim is open by appointment only. Please email gallery@mayyimhayyim.org or call 617-244-1836 ext. 211 to schedule a visit to view the exhibit.