There was a gag making the rounds last Passover, a mock announcement that proclaimed: “As you gather around your Passover seders next week, please remember there are a group of Jews who will have nothing to eat this Pesach…they are called Ashkenazim.” A year later, this joke is obsolete.

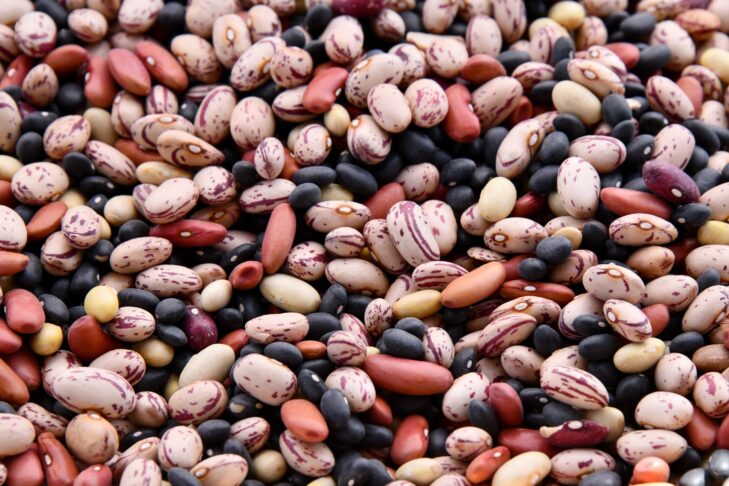

Having “nothing to eat” refers to the Ashkenazi custom of refraining from eating kitniyot (legumes) during Passover. Kitniyot include beans, buckwheat, caraway, cardamom, corn, edamame, fennel seeds, fenugreek, green beans, lentils, linseed (flaxseed), millet, mustard, peas, poppy seeds, rapeseed, rice, sesame seeds, soybeans and sunflower seeds. Peanuts were OK with some rabbis as long as the peanuts had kosher certification and no chametz was involved in their preparation.

Now the bean ban has been lifted, at least for Conservative Jews.

The kitniyot controversy harks back to medieval times. Ashkenazi rabbis decided that eating kitniyot should be prohibited because their similarity to chametz might confuse people. It’s a little more complicated, but that’s the gist. Thus, cutting out kitniyot became the minhag (custom) among Ashkenazi Jews.

Everything changed, to the surprise of many, in December 2015. The Rabbinical Assembly (RA), the international association of Conservative rabbis, issued two responsa explaining that it is kosher for Conservative Jews to enjoy kitniyot, from beans to sunflower seeds, for all eight days of Passover. The RA emphasized that they were not insisting that people eat kitniyot, but were offering an explanation as to why it’s OK if they do.

“The custom of not eating kitniyot on Pesach was first mentioned in France and Provence in the 13th century,” writes Rabbi David Golinkin, president and rector of the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem, in his responsum. “From there it spread to various countries and the list of prohibited foods continued to expand. Nevertheless, the reason for the custom was unknown and, as a result, rabbis invented at least 10 different explanations. For example, chametz sounds like chimtzei (hummus, or chickpeas); if we allow kitniyot porridge we will eat grain porridge because both are cooked in a pot; rice and kitniyot are sometimes mixed with wheat. The large number of explanations for not eating kitniyot proves that no one knew the real reason.”

“There are many good reasons to do away with this particular custom,” adds the rabbi, who heads the committee on Jewish law of the RA in Israel. “It detracts from the joy of the holiday by limiting the number of permitted foods. It causes exorbitant price hikes. It emphasizes the insignificant (legumes) and ignores the significant (chametz from the five kinds of grain). It causes people to scoff at the commandments; if we observe this custom that has no purpose, there is no reason to observe other commandments. And, finally, in Israel it causes unnecessary divisions between Ashkenazim and Sephardim.”

Wow, just like that. After 31 years of holding seders in our home, I can now contemplate adding rice to my chicken soup. Or can I? After all, it’s hard to break a habit, or custom, which for many years has been integral, if not inconvenient, to the celebration of Passover.

You know things have changed when Manischewitz comes out with a kosher for Passover line of products called Kitni, products including tahini, rice and lentils.

I asked some people how they felt about this new minhag. “Go for it,” my friend Stanley suggests. “I was sitting around the table last Shabbat discussing this issue. One person asked, ‘What is lost?’ In my humble opinion, not much. The tradition is half as old as the holiday. It’s not chametz. Period.” As a vegetarian, he notes, “All one can eat for protein during the holiday is eggs and cheese. And, for variety, cheese and eggs. Being able to eat beans, etc., opens up a whole world of options.”

“Let’s not rush into this,” was my husband’s response. I’m OK with that. It feels a little weird to contemplate consuming kitniyot at our seder. Not, the RA would say, that there’s anything wrong with that. Rabbi Amy Levin, who co-authored one of the responsa, was quoted in a recent article in The Forward. “I hear everything from, ‘Yes, we’ve already been sort of kind of playing with this already,’ to ‘Thank you, we’ve been wondering if we could do this,’ to, ‘I agree with you, but I don’t know if I could do this in my kitchen,’ to, ‘I’d be afraid that my seder guests might have a problem.’”

“The only reason to observe this custom,” asserts Rabbi Golinkin, “is the desire to preserve an old custom.” For some, that might be good enough. “Custom is often the initiative of the grassroots,” Rabbi Levin explains. “I have pots and dishes that were my grandmother’s. I don’t know if I’m putting lentils in my grandma’s pot. I’ll make lentils in mine. Because it’s kishkes, it’s this gut reaction to things. The gut reaction to things is very important in our tradition. It shouldn’t all be cerebral.”

Finally, my friend Marty adds his two shekels: “Interesting that at one point in time some rabbis thought that coffee beans were kitniyot. I can deal with no rice and beans for a week, but would never give up coffee.”

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE