I write these words on a Saturday night, after my kids have gone to sleep. I’m a rabbi, a teacher in a rabbinical school; I learn and teach Torah, write about it, for a living. In other words, this is my job. This is me, working on a Saturday night. Pretty depressing.

And on the other hand: I’m a Jew who loves Torah. I love my work, and I think it provides some value to the world. Even if I didn’t have a deadline, there’s a reasonable chance I’d be thinking about the upcoming week’s Torah reading anyway. And in any event, it has to get done.

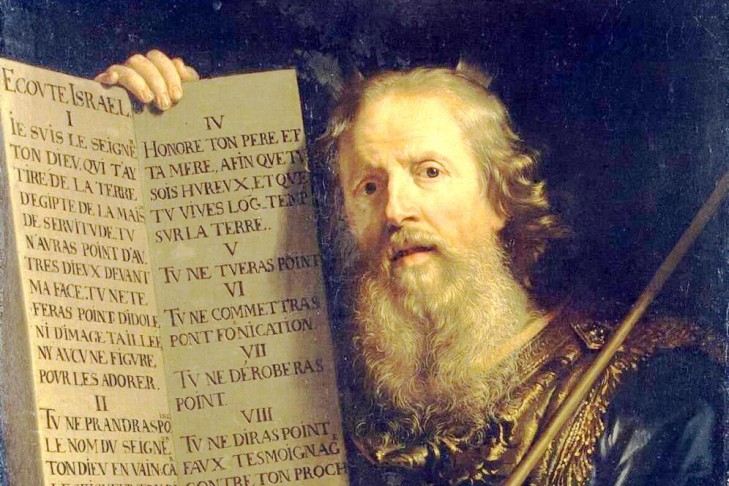

The Talmud (Tractate Shabbat 10a) tells a story of two sages, Rav Hisda and Rabbah son of Rav Huna, who would spend all day—“from morning until evening”—fulfilling their roles as judges for the Babylonian Jewish community. An early post-talmudic work called the She’iltot explains that these two sages were under the impression that they had to live up to the standard set by Moses in the opening of this week’s parashah: “Moses sat to perform judgment for the people, and the people gathered to Moses from morning until evening” (Exodus 18:13). Moses set the standard; if he was willing to work nonstop on behalf of the people, then we too, reason our Babylonian rabbis, must toil in service of the community, without rest.

And so, in what might be the most unsurprising next line of a story ever, the Talmud reports: “Their hearts became weak.” They got tired. Luckily, another rabbi was around to provide them with some sage advice. Rabbi Hiyya son of Rav, from Difti, points out that the verse about Moses clearly cannot be understood literally: “Is it possible that Moses sat all day in judgment? When did he learn Torah? When did he teach Torah?” In the rabbinic imagination, it is impossible that Moses’s administrative duties would have expanded so much that they would leave no time for the study and teaching of Torah. Rather, Rabbi Hiyya reports, the point of the phrase “morning until evening” in the verse is not to teach something about Moses’s literal daily practice, but to send you, the reader, back to the first chapter of the Book of Genesis: “It was evening, it was morning, one day.” What does that have to do with the story of Moses’s judging the people? “To teach you that any judge who renders a judgment that gets to the truth of the matter, even if for only one hour, it is as if they are a partner with the Holy One in the work of creation.”

Says Rabbi Hiyya: You don’t need to work so much. It’s enough to do your job “even if for only one hour,” so long as you’re doing it right.

But if I’m being honest, that’s not really so interesting. The message of quality over quantity is one that most of us get, at least intellectually. Sure, I might not live up to that standard, I might not set clear limits, such that the boundary between my work and my identity gets blurred, so that I no longer know when my time ends and my work begins. But at least in principle, I get it.

What’s most striking about Rabbi Hiyya’s response to the overworked sages, though, is that he encourages them to set boundaries not by denigrating the value of their work, not by saying, “It’s not that important,” but by upping the ante. If you do it the right way, he says, there’s nothing more important on earth. It’s as if you’ve taken part in creating a world. It is because what you are doing is so important that you can’t reasonably spend all day engaged in it.

The 19th-century scholar Rabbi Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin, also known as the Netziv, raises a problem, however, with comparison of Moses and the latter-day Babylonian sages. According to another passage in the Talmud, Moses was considered equivalent to the Great Sanhedrin, the rabbinic supreme court that was uniquely responsible for judging capital cases. And unlike other courts, the Great Sanhedrin was supposed to sit in session literally all day. Rav Hisda and Rabbah, sitting in Babylonia, were not judging capital cases, and therefore need not have looked to Moses as their model. And recognizing the distinction between Moses, on the one hand, and our Babylonian rabbis on the other, means that there may indeed be circumstances in which toil from sunrise to sunset is called for. It may be that living your mission in the world, when done with passion and limits, is an act on par with the creation of the very world. And even so, there remain specific tasks so important, so singular, that they indeed place on you what would otherwise seem an impossible expectation.

The challenge, of course, is knowing when you’re the Great Sanhedrin, engaged in work so potent and dangerous that you must push yourself up to and even beyond your limits, and when are you “merely” engaged in creating the world. There are no easy answers to that question. If you find yourself acting like Moses most days, though, you’re probably doing it wrong.

Rabbi Micha’el Rosenberg is an assistant professor of rabbinics at Hebrew College’s Rabbinical School.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE