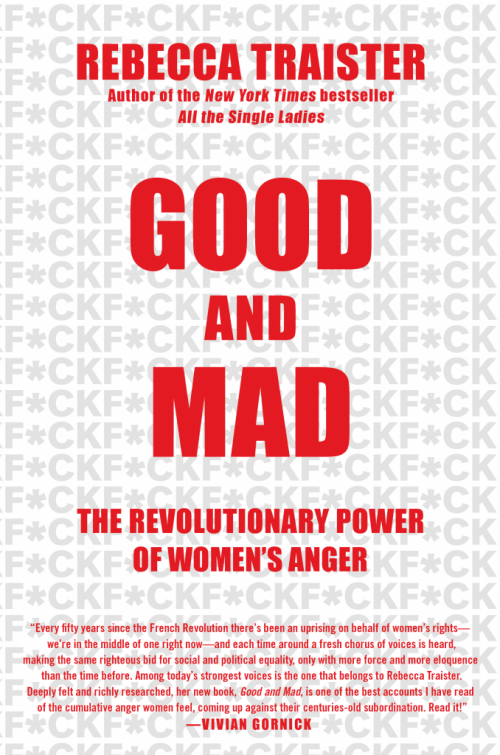

For Jewish writer Rebecca Traister, the anger and hope from the 2017 Women’s March on Washington—a rally that turned out to be the largest single-day gathering in United States history—make up the energy that inspired her new book, “Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Anger.”

In the book, Traister cites an Elle survey that found the news angered 83 percent of Democratic women at least once a day. But that anger was not only about the news of a given moment; women of color were angry with the 52 percent of white women who voted for Trump. Throughout her book, Traister parses the complexity of women’s anger. Her solution for quelling some of that anger is to recruit and train more women to run for office.

A recent headline on the front page of The Boston Globe declared: “Angry Women Upset Old Political Expectations.” Tell us about that.

Elizabeth Warren recently gave a speech about how angry she was. This is the anger that has been building, and it’s the reason I wanted to write a book in the past year that showed women’s anger as politically consequential. This anger has been erupting broadly through political protest and electoral politics. Telling #MeToo stories and stories of assault and power abuse is altering the world. Not to say that it’s fixing it, but it is disrupting the way things used to proceed. This is precisely why I set out to write a book chronicling women’s anger.

Why has this country not yet elected a woman president or, for that matter, a woman vice president?

I’ve written about Hillary Clinton for over a decade, and the gendered expectations that shaped who she was as a politician and candidate. It’s a subject that is closely tied to this conversation about anger, and expectations for how women comport themselves in public if they’re to be respected, let alone liked or approved of. Historically there has been a very narrow range of expression permitted to women in public. If they want to be taken seriously and respected, among the things not on the table is anger—an open, unapologetic expression of anger. That limitation of expressive possibility is related to some of the things Hillary Clinton and many women in public politics have faced. There are limited models for how women can comport themselves in public and political life. The model for what politicians look like has been male and largely white, and that is certainly the case for presidents.

Why did the Harvey Weinstein story stick more than the Bill Cosby or Bill O’Reilly stories?

It was the very slow building toward taking Bill Cosby and finally Bill O’Reilly and Roger Ailes seriously that paved the way for the Harvey Weinstein story to be taken seriously. It was also related to the election of Donald Trump, who had been credibly accused by many people of groping, and who had admitted to grabbing women against their will. Despite all of that, he was elected president. Yet the pressure was building to look seriously at things that had been open secrets for so many years. The Weinstein accusations were particularly horrific.

One of the things we need to reckon with is why the allegations were taken so seriously. It was because many of them were lodged by wealthy, famous, successful women. The public granted them an extra kind of authority because they were familiar with them. We need to reckon with what that means, and would those allegations have been taken as seriously if they were made by women who were not white, famous and wealthy. Why have we been more horrified, to some extent, by those allegations than those that have come out of the Ford factory plant or McDonald’s, where workers have been striking over sexual harassment? To say that is not to diminish the seriousness and gravity of the allegations made by those women. Another element was it showed even the most powerful women could sustain and experience misogynistic power abuse that damages them personally, physically, economically. It was a real view that it could happen to the most privileged. It shows how pervasive this behavior is.

What about Maxine Waters and the “vilification of black female anger?”

I wrote a lot about black women in the book, in part because of the stereotype and caricature that furious femininity is particularly attached to black women in the American imagination. There are a lot of reasons for that. For black women, there are a couple of different approaches. One is to turn it into a kind of cartoon for comedic or entertainment value. The other attaches the dissenting black woman to militarism. This is what happened to Maxine Waters and Michelle Obama. They were characterized as angry black women who posed a physical threat.

With Maxine Waters, Fox News tried to make hay of something she said about taking Trump down. She’s an example of how often black women, who have expressed anger in some way, are used by white women to express their own anger. She is somebody in this white capitalist patriarchy that is not supposed to have power, but who threatens power in some ways by channeling what is a mass dissatisfaction with the powerful white male president. She represents a kind of threat to that unquestioned and unchallengeable power.

Going back to her early political career, after the Rodney King verdict, she refused to characterize that unrest as riots or describe the people who were out in the streets as thugs. She saw anger and inequity, anger and injustice, and she understood that anger as an insurrection. That’s one of the points I’m trying to make in this book. Within a power structure, those who have less power, those subjugated or oppressed within that power structure, are often cast as being on a witch hunt. As Donald Trump has said, men are scared of the stories about how they have assaulted women.

This interview has been edited and condensed.