Millennials: aimless, idealistic, coddled. The stereotypes are rampant (and not helped by stories like this one, about parents who took their adult son to court to evict him from their house).

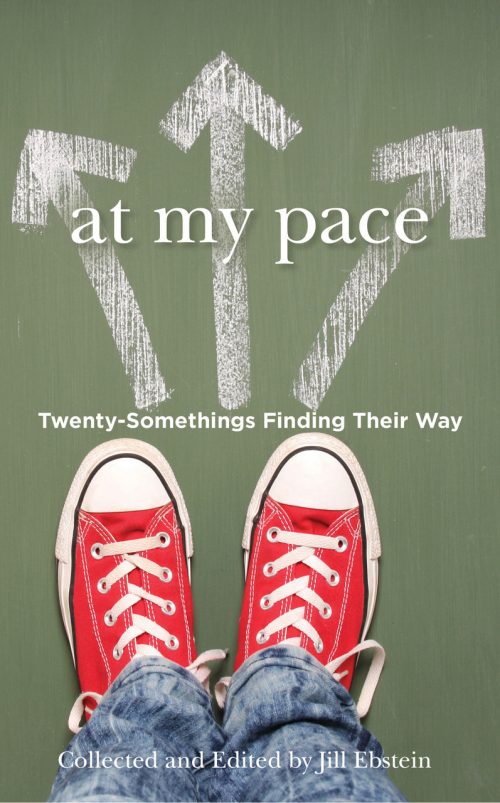

Author Jill Ebstein peers under the hood of young adulthood in her latest “At My Pace” series. The “At My Pace” books collect thematic essays spotlighting various life stages; in her first book, she focused on women who felt marginalized by the “Lean In” movement and embraced meandering career paths. (“Some women are on more of a winding road with rest stops,” she says.) Next, she gathered essays from adult children about lessons passed along by their mothers.

In this outing, she collected and edited 1,000-word essays from 20-somethings who share their coming-of-age stories, focusing on the disappointing, the melancholy, the alienating. One aspiring physician writes about “imposter syndrome” and whether she has the talent to succeed as a doctor; another author recounts an internal battle between pursuing a flashy but unfulfilling job and one with actual meaning; another breaks ranks with her parents to pursue an unexpected career. Ebstein found authors through friends of friends, she says, and she edited every one, prompting authors with questions, asking them to share their greatest disappointments or what they’d like their parents to understand about them. The experience was cathartic, she says.

“It was a chance for them to step back and add perspective and purpose to their story, and also a chance to explain or validate themselves to parents: Why am I doing this? Please understand.”

Ebstein, who has three grown children, hopes the book dispels myths about millennials as “aimless and lazy.” Instead, she says, “They’re living for their expectations, not ours, and have set high ones: They want financially meaningful but purposeful work. There’s no ‘clock in, clock out.'”

As for frustrated or nervous parents, it helps to “listen and embrace the process, and have confidence your kids will get there,” she says. “We have to help our kids to believe that they’ll figure it out and allow them, as painful as it is, to do it on their terms. It’s so easy for us to place our expectations on them.”

The struggle for an older generation to understand the younger one is nothing revolutionary, of course, but millennials grew up differently and more quickly than other generations, without traditional hierarchies and linear paths to upward mobility. Technology and social media offered easy access to glossy, picture-perfect lives and endless possibilities, as empowering as it was frustrating and jealousy-provoking.

“Technology is empowering in some ways. You feel connected. But if you’re looking to make a difference, it’s one thing to go on Facebook and instant messenger and declare things. To make a difference, to be a game-changer, is hard,” she says. “In my generation, we believed the hierarchy was justified; when people told us to do things, we did them.”

Ebstein hopes the book reveals unvarnished lives and helps other 20-somethings feel less alone.

“I love these kids. They’re not curated lives. There’s anxiety, depression, this is where I am and this is what I’ve learned. I love that they were able to be that way. Some people cried on the phone with me while working through their essays; others took them to therapy. It was helpful for them,” she says. “I hope 20-somethings will learn that everyone is going through this. Pain, anxiety, rejection is common. And if you’re honest and work hard, there’s good at the other end.”

As for parents?

“Realize that there’s a big gap between thinking ‘the world is your oyster’ and actually going out there and realizing how hard it is to be successful,” she says. “And, for them, success means different things: It means financial success, but also purpose and mission. These kids have been overly groomed for a career trajectory, and life doesn’t always work that way.”

So what’s a concerned parent to do? Ebstein has a suggestion:

“Go back and write your own piece about what your 20s were like. You forget these things.”

An idea for a new book, perhaps?