America’s founders understood the importance of separating matters of church and state. As the 2020 elections loom large, that bedrock American principle is under scrutiny. The Jonathan Samen Hot Buttons, Cool Conversations Discussion Series convened a panel to address the thorny question of faith and politics, and how religious communities navigate issues such as the immigration crisis, LGBTQ rights and the embrace of pluralism.

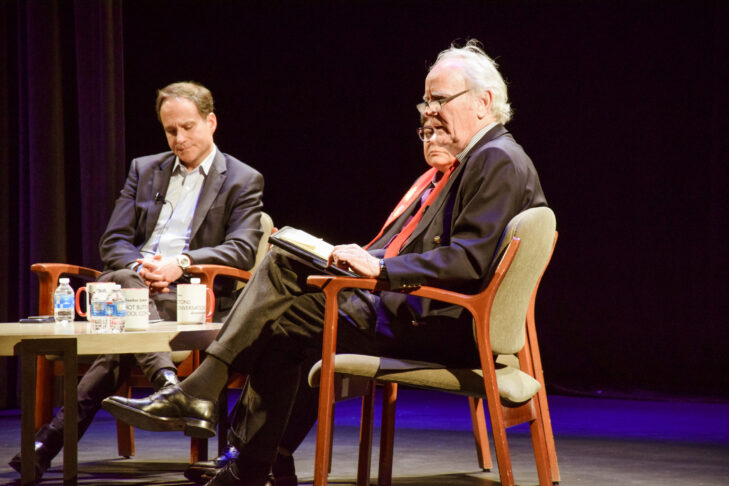

The distinguished writer and Roman Catholic reformer James Carroll moderated a conversation among Rabbi Jonah Dov Pesner, the Rev. Rhina Ramos and Dr. Khalil Abdur-Rashid.

Pesner is the director of the Reform Jewish movement’s Religious Action Center (RAC) in Washington, D.C. A native son of Boston and a former assistant rabbi at Temple Israel of Boston, Pesner took the social justice work he mapped out at Temple Israel and amplified it at RAC.

Ramos is a United Church of Christ minister in Oakland, California. A native of El Salvador, she is the senior minister at what she described as an “open and affirming Spanish-speaking congregation” with a focus on immigration and LGBTQ rights. Abdur-Rashid is Harvard University’s first full-time Muslim chaplain. He has teaching appointments at the Harvard Divinity School and the Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

Carroll framed the evening by noting that “we are living in a moment of tremendous moral, spiritual, religious and political challenge.” He charged the panelists with finding a language with which “to ask deeper questions about the conditions we’re experiencing.” He asserted that there’s an ongoing despair in American life that started around the time of 9/11.

As a witness to a revolution in El Salvador started by people of faith, Ramos asserted that she did not struggle with connecting faith and politics. She noted that religion and politics in El Salvador “were profoundly creative in terms of social justice.” She has brought that creativity to her congregation, which is also a base for her community organizing and social justice work. In that work, Ramos “faces the reality” that the lives of LGBTQ asylum seekers are often targeted. At the same time, she also works to provide basic necessities to the undocumented in her church. “As a pastor, I have to think about my resources and worry about feeding somebody,” she said.

Abdur-Rashid described himself as a proud son of the South. He grew up in Atlanta and his parents were Southern Baptists who converted to Islam in the 1970s. As a boy, he recalled that his parents were “enamored” of Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam. He noted that his childhood was spent with “one foot in the civil rights movement and the other foot in the African-American Muslim community.” For Abdur-Rashid, the Nation of Islam represented an American Islam that radically differed from global Islam in its approach.

The panelists concurred that the plight of the poor and the downtrodden needs to be the immediate focus of an interfaith social justice movement. “There is a gap in civil rights,” said Abdur-Rashid. “It speaks to a large contingent, but not the total contingent. The activism that intersects with the civil rights movement has its origins in black Islam and Southern Baptist roots.”

Pesner said the religious roots of the civil rights movement are evident in the Rev. William Barber’s action to reinvent the Poor People’s Campaign as one that is “a national call for moral revival.” Pesner noted: “We’re not transforming our community to be the beloved community it could be. We need to become more proximate—to get our congregations to be in relationships with communities that don’t look like them. Shared solutions to shared problems happen when you’re in a relationship.”

Pesner also pointed out the critical relationship between Jews and blacks—a relationship that came of age during the civil rights movement. According to Pesner, the RAC was Martin Luther King’s de facto office in Washington. It was the site where the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was drafted, as well as the Voting Rights Act of 1965. “The civil rights movement was a faith-based movement,” said Pesner.

Ramos’s overarching issue has been to present immigration as an innate human right. “We need to welcome those among us that are foreigners,” she said. That injunction speaks to a pluralism that goes back to the Old and New Testaments. “We need to humanize people,” Ramos said. “We need to see all immigrants, not just the poster child for immigration that makes it to higher education and becomes a public figure. We also need to see the immigrant child who is struggling and homeless.”

The program ended with a call for a dynamic American pluralism. Abdur-Rashid identified the immediate need for “a robust pluralism” within the American Muslim community. “The interpretations and teachings of Islam have been imported [to America],” he said. “There is not one accredited Muslim seminary in the United States. Our leadership in the United States is from overseas. That’s why [the Muslim community] does not have robust interfaith alliances or robust political agendas. We need thriving institutions that can engage with the Jewish and Christian communities. We don’t have that leadership in place yet.”

Ramos predicted that forging strong pluralistic ties would happen once people “are ready to receive the multiplicities that exist in the United States.” Pesner illustrated his vision of a new pluralism with the biblical stories of Adam, Abraham and Sarah. “We’re created from one person from which unity and gender fluidity flow,” he said. “I struggle with the concept of [Jews] being chosen. We Jews were chosen for a pluralistic mission and a purpose not because we are better, but one which distinguishes us as Jews. We have the radical hospitality of Abraham and Sarah to follow.”