Whenever I tell anyone I’m half-Egyptian, their reaction is some variation of, “That’s so cool!” Several people think I mean ancient Egypt with Ra and hieroglyphics and mummies; it’s a vibrant culture so I get that assumption, but that’s not the case.

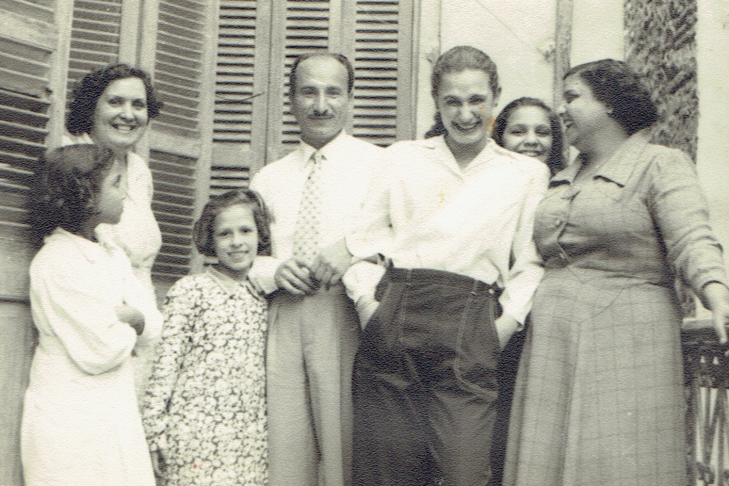

My maternal grandparents, Rachel and Joe, were born in Egypt and had an arranged marriage. Rachel was 15 years old and Joe was 33. They were expelled from Egypt for being Jewish, went to France, had my mom and came to the United States, settling outside of Baltimore. And that’s it.

My parents, brother and I used to spend one night of Passover with Grandma Rachel and Grandpa Joe when they still lived in Maryland and my grandfather had his memories. Because of their history, I felt some sort of small connection to the Passover story, or maybe in my naïveté I just made one up in my head. “The Ten Commandments” was on a constant loop every spring, so naturally I was convinced my grandparents were slaves. “You called me and you said to me, ‘Grandma Rachel, were you a slave? Were you a slave?’ I said, ‘No, Ashley, I wasn’t a slave.’ It was so funny,” she told me.

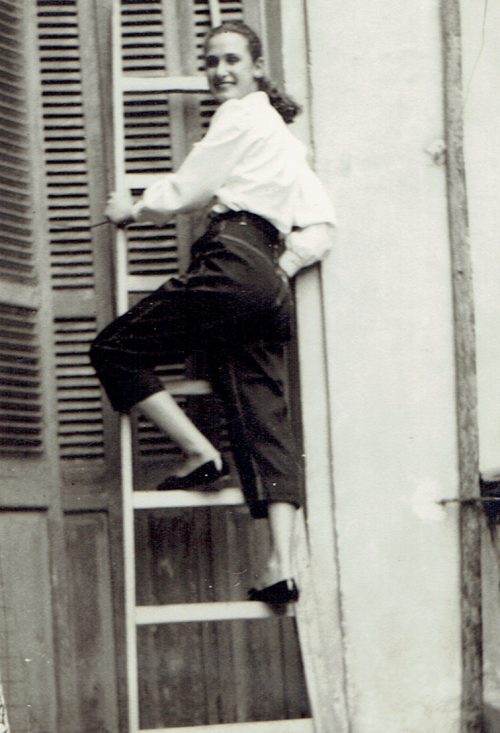

When you’re a child, adults leave out part of the truth and everything is romanticized. As a kid in museums, I beelined it to the ancient Egypt exhibits to “hang with my ancestors.” I learned how to properly pronounce “cumin” in college (it was always “cumoon”). My eyes are a point of discussion with most Middle Easterners I meet. And the only way to make falafel is with fava beans, not chickpeas. I wasn’t told how awful Egypt was, just that my grandparents were forced to leave.

In retrospect, I didn’t have all the pieces of my mom’s family history because I never asked for the details; I wrote it off as a touchy subject. When my new job at JewishBoston had me brainstorming content ideas for Passover, I knew it was time to dig deeper into the short narrative with which I grew up, so when I saw Grandma Rachel at a b’nai mitzvah last month, I had some questions.

“I left Egypt in 1956,” she said. We did the math. “It’s been 61 years. Forget about Egypt.”

The next day, I told her I wanted to write about her for work and speaking with her would help me do my job. In typical grandmother fashion, she gave in.

Grandma Rachel traces her family’s roots to Egypt, stopping at her great-grandparents, unsure of their past. She thinks her grandfather was part Russian. My grandfather’s grandfather came from Tunisia but the rest about his side is a mystery; Grandpa Joe died with Alzheimer’s in July 2010.

Grandma Rachel summed up her immigration story as soon as she could, after my first question (“How old were you when you left?”): “I was 16. I got your mother when I was [almost] 17, so your mother was born in Paris. And we came to America, Baltimore and we made our life.” And then she laughed like she couldn’t believe she was telling me this.

I pressed on. “What was it like in Egypt before you left?”

After school every day, Grandma Rachel would go to what she calls a “nun school” and learn how to sew and embroider from the sisters. Her parents had to pay for it and she went there for two years. “That time in Egypt, and maybe it was all over the world, we didn’t go to college,” she said. “College wasn’t offered to us. Nobody went to college.” Her parents expected her to live and make money working as a seamstress. Great-Grandpa Lichaa worked at a jewelry store that went bankrupt, then at a bicycle shop, then a bakery. Great-Grandma Luna was a seamstress who made suits and dresses.

Under Gamal Abdel Nasser‘s rise to power, the Egyptian government started to “give trouble to” and threaten the Jewish people. “They would say, ‘Here is a Jewish girl.’ And you know that they hate the Jewish people. And once they say “Here is a Jewish girl” or anything, you get scared. So you run. It wasn’t a good feeling.”

Grandpa Joe had a jewelry store, which, along with all their jewelry, money and car, the government took. “We never got it back,” she said. “We were happy to just get out [of Egypt] because we were afraid they’d do something to hurt us.”

Grandma Rachel and Grandpa Joe were able to leave Egypt for France because my grandfather’s family had a Tunisian passport. Grandpa Joe’s siblings and his mother went with them. Grandpa Joe worked repairing clocks; Grandma Rachel gave birth to my mom and they lived “day by day” in Montmorency, a commune less than 10 miles north of Paris. Luna and Lichaa didn’t have a foreign passport so they couldn’t leave Egypt.

France was “nice,” Grandma Rachel said. “But I missed my parents. It was a very bad time for me. They say that ‘Paris is for the lover’ or stuff like this. I didn’t look at it this way. I missed my family in Egypt.”

My grandparents immigrated to the United States in 1959, settling outside of Baltimore with only $300, which Grandpa Joe hid in a tube of toothpaste. My uncle was born a few years later. Five years after coming to the States, they became American citizens and my grandmother was able to bring her family over.

“We know [America] is a beautiful country, we know you can make a living. My mother had an uncle who lived in Philadelphia,” said Grandma Rachel.

“Why did you go to Baltimore?” I asked.

“I didn’t have any choices. My luggage was supposed to go to Philadelphia and accidentally went to Baltimore. So we stayed in Baltimore.”

Grandma Rachel kept working until Grandpa Joe got sick, and is “now retired in Florida,” she said with a half-shrug, half-laugh. Hoping to continue lifting her spirits, I asked her about one of her favorite memories before things got scary in Egypt.

She sat thinking. “I didn’t have a favorite memory.” She paused. “I lived with my parents and this time, all the children lived with the mother and the father. It’s not like today, you go away to college or something. No, no, no, no, no, it was a family, you all stay together, eat together and that’s the way it was.”

Trying to elaborate on this theme of generational differences, I inquired about what she learned from her experiences and what she wants people to know.

“There’s nothing to be learned about this stuff. You don’t learn, you just go through it…There was a time Egypt was beautiful…But I don’t know how it looks now…People don’t understand why I don’t want to go back. I don’t want to go back. I won’t feel free. I will be scared to go back. And that’s it.”