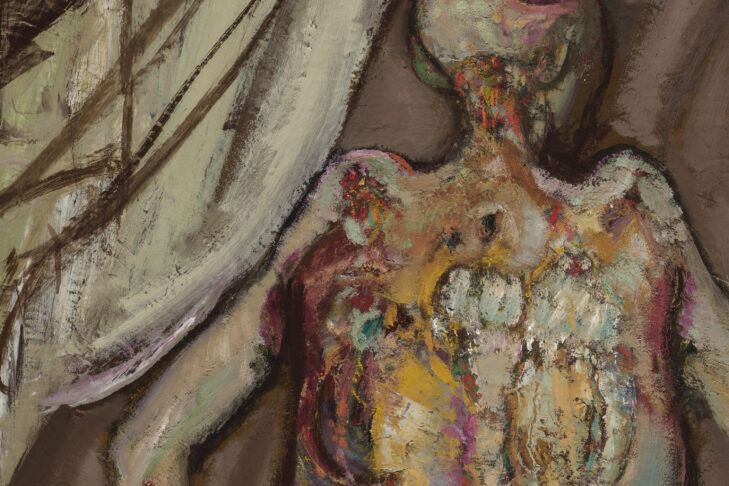

Flying brides with uteruses and fetuses exposed, decaying corpses splayed on tables, innards of cadavers with blood-red muscles that are front and center—the images disturb and fascinate in the long-awaited show of Hyman Bloom’s dazzling work at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. The show is appropriately entitled, “Hyman Bloom: Matters of Life and Death.”

Bloom was born in 1913 in Latvia. His family came to the United States in 1920, where they settled in Boston’s West End. Bloom’s artistic talent was evident at an early age, identified by one of his teachers. Beginning in eighth grade, he attended art classes at a local community center.

By the late 1930s, Bloom’s career was in full swing. His earliest subjects included depictions of synagogues and brides—work that drew favorable comparisons to fellow Jewish artists like Chaim Soutine and Marc Chagall. He attracted the attention of Alfred Barr, the first director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, and was soon in league with artists like Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock. When Bloom died in 2009, his obituary in The Boston Globe described his paintings as a combination of William Blake and Michelangelo.

In the early 1940s, a close friend of Bloom died by suicide, and her family asked him to identify the body at the morgue; that was a turning point for the artist. Although Bloom had turned away from Judaism, the encounter influenced his emerging spiritual life and changed the direction of his art. In response to the experience, he wrote, “I had a conviction of immortality, of being part of something permanent and ever-changing, of metamorphosis as the nature of being.”

Bloom’s fascination with corpses and death was reinforced after he went to Kenmore Hospital in Kenmore Square with an artist friend. Erica Hirshler, who curated Bloom’s show and gave me a personal tour of the exhibition, observed: “Artists have always been fascinated by the morgue. The way to learn about the human body was through autopsies and anatomy lessons. There are graphic images from a 16th-century anatomy book that showed the human body flayed and hanging from a rope. The connection between doctors and artists has always been there.”

As Hirshler and I walked through the rooms displaying Bloom’s graphic art, she emphasized that the show was not intended to be a retrospective. One of the themes Bloom repeatedly explored was “to get beneath the surface of things—to learn more and to excavate.” Hirshler further pointed out a group of paintings that appeared, at first glance, to be abstractions. Upon closer inspection, one of the works entitled “Treasure Map” is based on a site map of an archaeological expedition in Greece. “Excavation is a way of finding truth and value,” Hirshler said, “and it is a way of carrying out the explorations of the human body in the later works in the exhibit.” To Hirshler’s point, “Archaeological Treasure” and “Treasure Map” have a more aerial view, and their horizontal layouts conjure autopsies and dissections on cadavers. These dazzling paintings, done a decade after World War II, are among Bloom’s most influential works.

When we reached the rooms where Bloom’s paintings of human corpses and Chagall-esque brides hang, Hirshler noted that the work was done in the late 1940s, “when the Jewish people were starting to come back to life from the Holocaust. Bloom was attracted to the opposites of light and dark, life and death. Note that the brides in [“Horizontal Brides”] have veils that echo shrouds. The attraction of opposites is fascinating. You can’t tell if they are alive or dead. The painting depicts the different phases of a person’s life.”

One might think that Bloom’s later art reflects an obsession with mortality and death. But as Hirshler observed, “Bloom’s encounter with these difficult subjects is more about life than death. He encourages one to view what is beneath the surface of the work.” As we went through the exhibit, I was captivated by Bloom’s “hot colors and energetic brush strokes.” His self-portrait is a work pulsing with life as blood courses through the body. The power underneath the painting is very much a part of the work.

One question looms large in this show: Why wasn’t Hyman Bloom as famous as his contemporaries? In the 1960s, he represented the United States in the Venice Biennale. He also showed his work at the University of California in Los Angeles with the British artist Francis Bacon, also known for his preoccupation with the human body. “Bacon is equally violent, equally contorted and equally graphic,” said Hirshler. “The reds and oranges in both men’s work are hot. They are initially abstractions until you realize what you’re looking at.”

Perhaps Bloom’s relative obscurity was due to his reluctance to involve himself in the politics of the art world. He wasn’t a glad hander. A famous anecdote about the artist recalls that when museum curators visited his studio, he turned his paintings toward the wall. Was it modesty or embarrassment about his work that made him conceal it? We’ll never know. But one thing is sure: Hirshler has assembled a grouping of Bloom’s work that unequivocally affirms his genius.

“Hyman Bloom: Matters of Life and Death” is on display at the MFA through Feb. 23, 2020. Find more information here.