When people admire my frequent traveling, I always say yes, but it’s budget travel. “But that’s the best way to really see places,” they usually respond.

It’s true. Not only do I get to mingle with locals and walk all over, but on buses and trains, you see the outer landscapes.

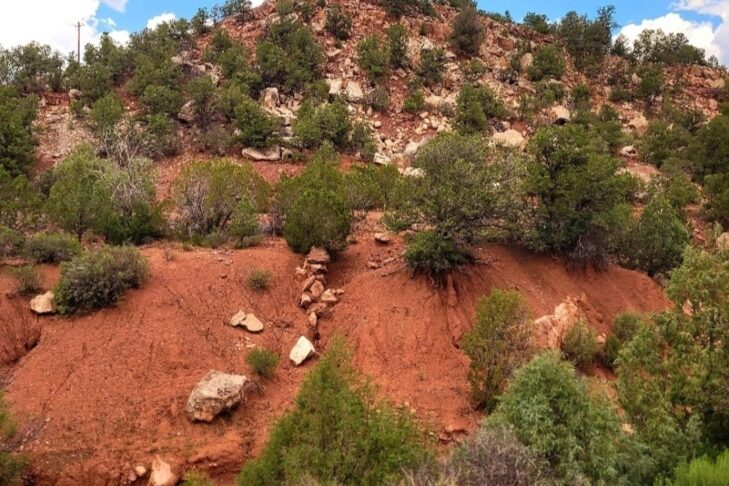

You see the fields, the hills, the bodies of water, the crops and the grazing animals. When lucky, you see the coast. And when super lucky, you see the trees.

“I think that I shall never see/A poem lovely as a tree,” wrote Joyce Kilmer in 1914.

“A tree whose hungry mouth is prest/Against the earth’s sweet flowing breast;/A tree that looks at God all day,/And lifts her leafy arms to pray,” he beautifully and aptly continued. And he humbly finished: “Poems are made by fools like me,/But only God can make a tree.”

This is spiritually true. The Torah contains many passages that praise trees, and warn against cutting them down.

And in Deuteronomy 15:27, Rabeynu Bachya said the 12 springs before them in Elim represented the 12 tribes, and the 70 palm trees, the 70 then nations of the world.

In a July 14 Boston Globe op-ed about the current climate crisis, Marie E. Antoine and Stephen C. Sillett of Humboldt State University of California referred to trees as “one part of the solution growing all around us.” They explained how trees alone can’t save the world, but can help.

“Few organisms are as incredible as giant trees,” they wrote. “Contemplate the sheer magnitude of what they do. A tiny seed finds a nook for germination. The seedling roots connect to symbiotic soil fungi. The sapling forages for resources—light, water, nutrients. The treetop grows hopefully ever upward…Its lifespan may be long enough for human civilizations to rise and fall.”

Human awareness and behavior certainly seem to fall far more than rise. But Antoine and Sillett, calling trees “biodiversity refuges and massive carbon sinks,” find some salvation. “They occupy only a small portion of the planet’s surface, but they store huge amounts of carbon and provide critical arboreal habitat,” they write.

During the pandemic, people headed outdoors and rediscovered the joys of walking in nature. They felt its healing, calming influence. They breathed in the negative ions, and a connection that had been lost in all of the hustle and bustle of life as we knew it. The trees were waiting for us, giving, not taking, as always.

Our sages well understood this. In “A Garden of Choice Fruits (Shomrei Adamah, 1991), Rabbi David E. Stein cited Rabbi Abraham ben Maimonides: “In order to serve God, one needs access to the enjoyment of the beauties of nature—meadows full of flowers, majestic mountains, flowing rivers. For all these are essential to the spiritual development of even the holiest of people.”

On April 25, five days before Arbor Day, Globe columnist Thomas Farragher featured Boston arborist Max Ford-Diamond, who cares for the health and wellbeing of some 40,000 area trees.

“This is a guy who helps put the emerald in the Emerald Necklace,” Farragher wrote.

The outlook for Boston is encouraging. “Each year, we plant between 1,000 and 1,600 trees,” Ford-Diamond explained. “This year, we’re hoping to plant 2,000 trees. We got a very large increase in our budget, thanks to the City Council. We went from $750,000 to $1.7 million.”

“That’s a lot of trees,” Farragher marvels.

We need every single one.

Tu BiShvat, the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Shevat, is called “Rosh HaShanah La’Ilanot,” or “New Year of the Trees.” It’s a grand, green celebration.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE