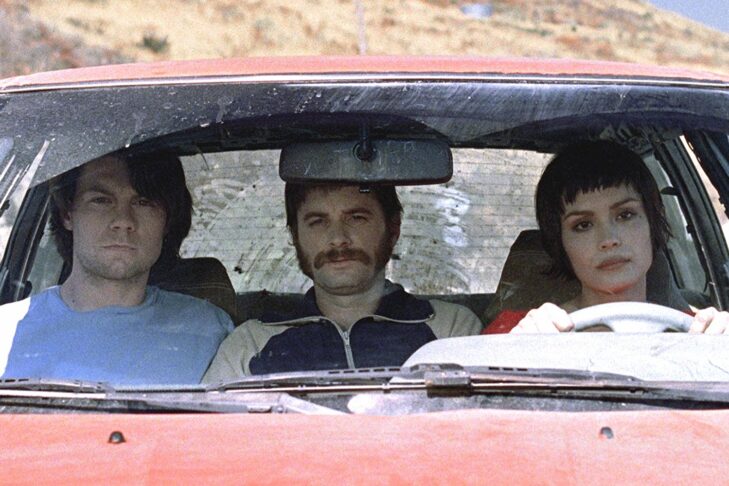

When I was in college, the woman I now call my fiancée put on a film called “Wristcutters: A Love Story,” and I have thought about it every day since that moment. The film, a biting black comedy about an afterlife populated only by people who died by suicide, follows hapless, lovesick Zia as he, along with his friend Eugene and hitchhiker Mikal, tries desperately to find his ex-girlfriend after he learns of her death. Attaining cult status after its release in 2006, “Wristcutters” is equal parts funny, romantic and deeply dark. It is also, I learned, super Jewish.

I always got the sense that “Wristcutters” was inherently Jewish. Perhaps it was the strong Eastern European vibes, the pilgrimage through the desert wasteland, the minute miracles Zia is so desperate to perform when the trio reaches “Kneller’s camp.” And then I got my hands on the novella on which the film is based, “Kneller’s Happy Campers.”

The author, Etgar Keret, is an Israeli writer with a penchant for light absurdism and just a touch of grief. In the book, Mordy and his friend Uzi are also Israeli, and the themes of Judaism play throughout their journey more so than in the film. I was absolutely floored.

For a lot of Jews, the afterlife is a sticky wicket. Some subscribe to a physical afterlife, some to reincarnation, some to a vast expanse of nothingness. And because we’re Jews, and because we love to ask questions, it’s next to impossible that we will have a concrete answer (and even if we did, someone would want to debate it). Which is why Keret’s afterlife is so compelling to me.

Mordy describes this world as just like the world of the living, but slightly worse. In the film, Mikal comments on how it’s impossible to smile, and how there are no stars in the sky. The landscape is lit up in harsh white, where the sun is always shining, albeit unpleasantly. The humor of this other world is also darkly referential to the fates of its inhabitants. Mordy gets a minimum-wage job at Kamikaze Pizzeria and plays a game with two girls in a bar, where they try to guess how other patrons “offed” themselves. This wry Jewish humor, however grim, gives both the book and the film a certain levity, that “haha…oh” moment that is so difficult to pull off.

But it’s not just the humor that makes “Kneller’s Happy Campers” so Jewish. After all, traditional Jewish law prohibits suicide, though contemporary views are mixed. The climax of both the book and the film involve the Messiah King (nicknamed “J”; three guesses to whom it refers!), who plans to perform a miracle by killing himself a second time. The novella and film deviate at this point, but the theme of carrying on through misery is clear. Regardless of whether or not Zia/Mordy gets the girl, he’s forced to keep living.

Heaven and hell have always been culturally present, but so infrequently do we see the Jewish afterlife in media. Keret’s take breaks away from traditional preconceptions of life after death and instead creates this oppressive, wonderful, Jewish farce.