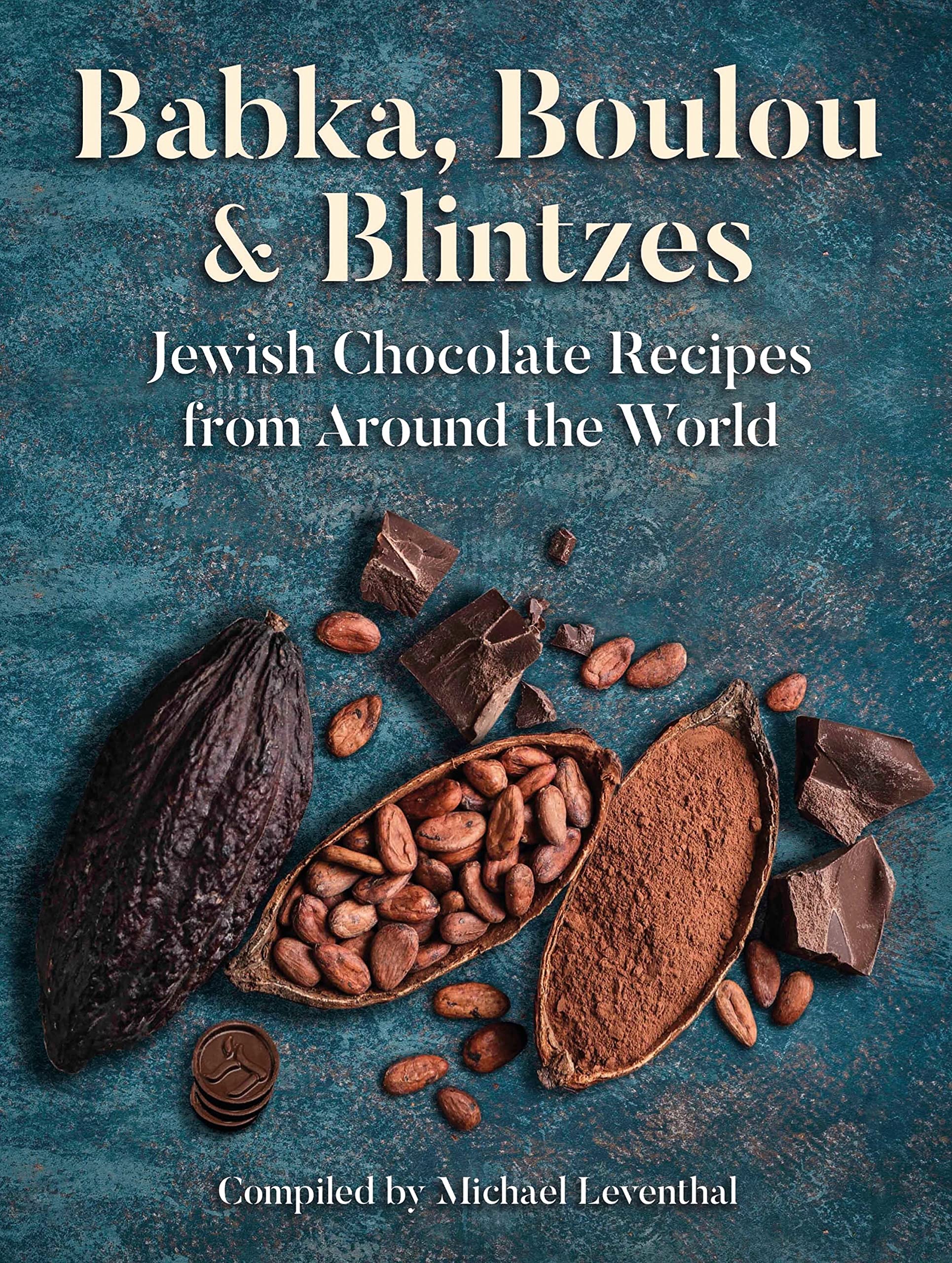

First discovered thousands of years ago in Mexico, chocolate is enjoyed across the globe today. During the Renaissance, Jews played a little-known but crucial role in helping to popularize the sweet stuff. Ever since then, Jews have been part of the story of chocolate, from rugelach to Hanukkah gelt. This narrative is shared—along with plenty of recipes—in a new book, “Babka, Boulou & Blintzes: Jewish Chocolate Recipes from Around the World” by London-based author and publisher Michael Leventhal.

“Most people eat—and like eating—chocolate,” Leventhal said in a Zoom interview. “It’s also a part of history that very few people, even in Jewish communities, know about. It surprises people, delights people, interests them. They learn a little bit, taste a little bit of history.”

Leventhal’s interest in the narrative of Jews and chocolate arose out of a Jewish food charity he founded, Gefiltefest. Through his work on the charity, he learned that in the 1600s, Jewish chocolate-makers in Spain fleeing the Inquisition escaped over the border to southern France—specifically the city of Bayonne.

There, he said, “they set up the first chocolate-making workshops in France. [Bayonne is] still today known as the chocolate center of France, thanks to the Jews that came there from Spain.”

Three summers ago, Leventhal brought his wife and their two children to Bayonne. They visited chocolate shops, a chocolate museum and the Jewish cemetery.

“My son Sammy, who was 6 years old at the time, said, ‘I am sick of chocolate. I never want to eat chocolate again!’” Leventhal recalled after countless tastings. “His resolve did not last. I think it’s quite a challenge to turn a 6-year-old off chocolate.”

Learning about the history of Jews and chocolate inspired Leventhal to write a children’s book about the subject—”The Chocolate King”—through the publishing company he runs, Green Bean Books. It also inspired him to seek out recipes from 50 acclaimed cooks around the world for “Babka, Boulou & Blintzes,” which would also be a fundraiser for the British charity Chai Cancer Care. Leventhal said that Chai serves many families in the UK. His mother, who has lung cancer, receives support from Chai.

“Most people I contacted were very happy to help provide a recipe,” Leventhal said.

They include Joan Nathan, author of “King Solomon’s Table,” and Rabbi Deborah Prinz, who wrote a previous book about Jews and chocolate, “On the Chocolate Trail.” Both Nathan and Prinz sent cake recipes from Bayonne—a chocolate almond cake and a Basque chocolate cake, respectively. Nathan’s recipe was passed down among generations of a Jewish family, with additions over the centuries, including rum.

“I have tried her cake,” Leventhal said. “The recipe is more than 400 years old. It still works well. Claudia Roden said, ‘Every recipe tells a story.’ This proves if any recipe has a story, this is it. It’s a 400-year-old recipe that tells you so much about the movement of the Jewish people.”

Roden contributed Spanish hot chocolate recipes to both “The Chocolate King” and “Babka, Boulou & Blintzes.” In the latter, hers is one of three hot chocolate recipes, alongside Claudia Prieto Piastro’s Mexican hot chocolate and a recipe from the Caribbean island of Curaçao. Hot chocolate is a traditional drink at a brit milah (bris) in Curaçao, complemented by sponge cookies called panlevi, for which the book also shares a recipe.

Piastro’s hot chocolate reflects ancient traditions in Mexico, where thousands of years ago, indigenous people first learned to make a drink from the cacao plant. She writes that cacao beans were traditionally ground using a metate—a mortar comprising volcanic rocks—before the mixture was dissolved in water to make hot chocolate, initially consumed as a ritual drink. She notes that you can try making her recipe by grinding the cacao nibs with cinnamon and allspice in a mortar, although the process can take at least a half-hour by hand. She also writes that it was only after the Spanish conquest that sugar was introduced as a sweetener to hot chocolate by Europeans.

The book features other savory chocolate recipes, including Alan Rosenthal’s chocolate chili. He prefers making chili con carne with chuck steak and dark chocolate. Denise Phillips sent a Sicilian recipe for a dish called caponata, with multiple regional variations across the nine provinces of the island. Her ingredients include dark chocolate and multiple vegetables, starting with three eggplants. She writes that it is “perfect for Yom Tov and Shabbat lunch.”

There are multiple holiday recipes. Boulou, the Tunisian cake-slash-biscuit recipe contributed by Fabienne Viner-Luzzato, is traditionally enjoyed with black coffee at the end of Yom Kippur, while Nathan’s cake recipe includes a matzo cake meal option for Passover. Marlena Spieler shares a recipe for chocolate matzos with crystallized ginger, while the final recipe in the book is the Purim-themed hamantaschen with chocolate and poppy seeds from Evelyn and Judi Rose that the authors note is a blend of Sephardi and Ashkenazi styles.

Readers can also learn about the history of chocolate in Israel—including Latvian immigrant Eliyahu Fromenchenko, who immigrated to Mandatory Palestine and founded the Elite chocolate company. In Adeena Sussman’s olive oil chocolate spread recipe, she recalls an Israeli memory—“Hashachar Ha’Oleh (“Rising Dawn”), a cheap sugar rush of spreadable chocolate that “used to give Nutella a run for its money.”

Leventhal cited the sugar rush in discussing why chocolate is so popular today.

“I guess there are very few things, very few foods and drinks, that have a universal appeal,” he reflected. “It’s fair to say a majority of us like a little sweet treat from time to time.”

Want to try a recipe from the book? Learn how to make molten brigadeiro cakes or Curaçao hot chocolate and panlevi!