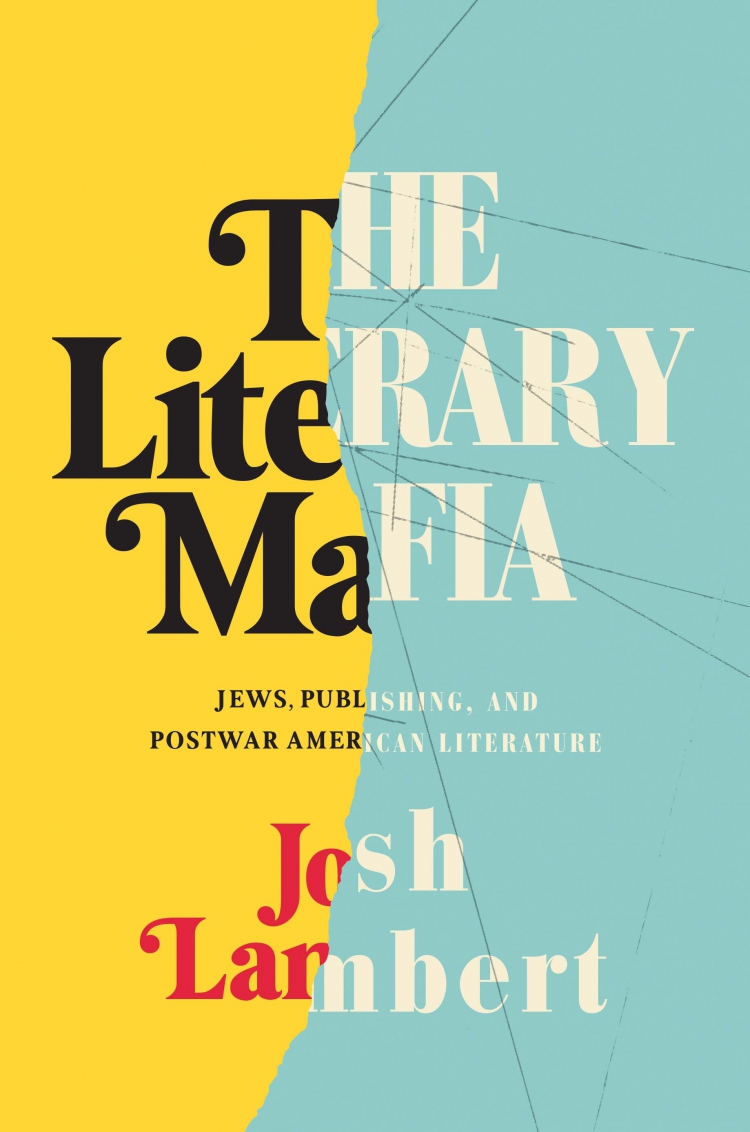

In the early 20th century, the American publishing world was largely closed to Jews due to antisemitism. As time passed, Jews found roles in the industry, with some even establishing their own publishing houses. Yet this rise to prominence came at a cost. By the 1960s, writers including Truman Capote and Jack Kerouac were contending that a Jewish literary mafia controlled publishing in the U.S. Wellesley College professor Josh Lambert disproves these claims in his new book, “The Literary Mafia: Jews, Publishing, and Postwar American Literature.”

“Frankly, it’s an academic book with tons and tons of endnotes,” Lambert said. “I did not necessarily expect it to get talked about in all these different places. It appears today that this topic is interesting to people.”

The book follows the ascent of Jews in the publishing industry over the course of the 20th century. When the century dawned, antisemitism kept Jews out of publishing. Over the first half of the century, immigrant Jews created their own space in that world, sometimes using inherited family fortunes to do so. Sometimes they helped each other, but the overall dynamics were far more complex than the crude claims of Capote or Kerouac. And, as Lambert points out, in 1953—the only year in which he could find a majority of Jewish judges on the National Book Award panel—the prize went to Black novelist Ralph Ellison for his seminal novel “Invisible Man.”

At the outset of the century, Jews could not get jobs in the field due to antisemitism.

“In the publishing industry in 1903 or 1915, if you were Jewish, you got turned away,” Lambert said. “Jewish students who were studying in fancy schools, studying literature, would get told pretty explicitly, ‘[publishing] isn’t for you…you won’t succeed, you won’t get a job.’” He cited a translator named Isaac Goldberg, who received a Ph.D. from Harvard in 1912 but could not find a publisher for his autobiographical novel, which plunged him into depression.

However, starting in the early decades of the century, some Jews founded their own publishing houses. The husband-and-wife team of Alfred and Blanche Knopf established their eponymous company, while business partners Bennett Cerf and Donald Klopfer founded Random House, which eventually became the nation’s largest publisher. In a similar partnership, Richard L. Simon and M. Lincoln Schuster created Simon & Schuster.

Antisemitic depictions of Jewish publishers marked literature of the period, including the character of Robert Cohn in Ernest Hemingway’s “The Sun Also Rises.” Lambert found other examples in the works of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Edith Wharton. And yet, real-life Jewish publishers were becoming more prominent by the 1920s.

“Part of it was their investment, part of it was their commitment and willingness to take risks,” Lambert said. “The other piece of it,” he added, was that “many of the Jews were incredibly hard-working, brilliant, willing to jump through all kinds of hoops,” including “taking all kinds of antisemitic abuse or disrespect and fighting their way through.”

One example of risk-taking by Jewish publishers was Random House’s 1920 gamble on “Ulysses” by James Joyce, which Lambert explored as part of his previous book, “Unclean Lips: Obscenity, Jews, and American Culture.”

“It required a very significant legal strategy,” Lambert said. “It was certainly a risky thing to do. If it failed, they would lose this investment they made in the book. It succeeded wildly. It was a huge success that helped Random House become what it is.”

Ironically, publishing houses headed by Jews sometimes published books with passages that could be viewed as antisemitic. Lambert mentioned Knopf publishing T.S. Eliot’s poetry and H.L. Mencken’s literary criticism.

“One of the things they felt very clearly was that antisemitism was not scary to them,” Lambert said. “They were not worried about it. They were not troubled when T.S. Eliot wrote a poem that seemed to express a kind of virulently hateful belief that Jews were the scourge of European society.”

He added, “It was the same thing with Mencken. In 1930, he published…just a really mean-spirited paragraph about Jews. The Knopfs didn’t seem to worry about it at all.”

One thing that troubles Lambert is how antisemites have misinterpreted his own books, including on social media and in articles masquerading as scholarly publications.

“I think that this new book hasn’t seen that much yet, but there have been a couple of tweets from what seem like openly antisemitic accounts,” Lambert said. “They say ‘this Jewish academic says there’s a literary mafia controlling things.’”

Related

However, he added, “I don’t think antisemites should get to decide what research gets done in Jewish studies, or get to decide what conversations happen within Jewish communities. I think that the impulse not to talk about something because of what antisemites might say about it feeds too much power and control to those antisemitic voices.”