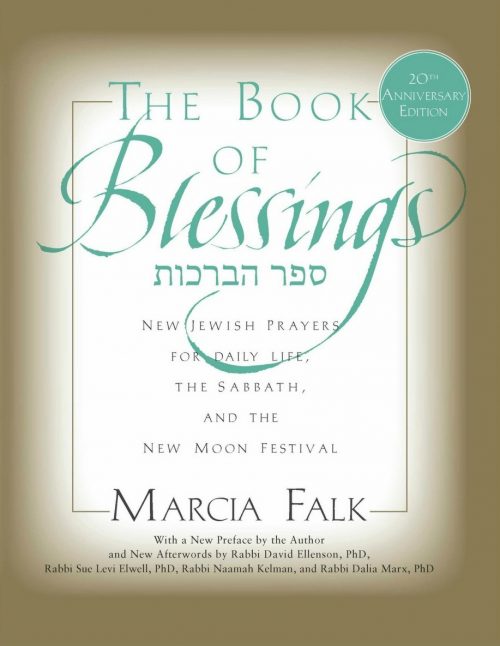

Earlier this month, poet and artist Marcia Falk released the second edition of her iconic “The Book of Blessings: New Jewish Prayers for Daily Life, The Sabbath, and the New Moon Festival.” She spoke with JewishBoston about the theology that inspires her work and the relationship between her visual art and poetry.

How did you come to write blessings?

I grew up as a Conservative Jew, and in my 30s I was part of a Conservative minyan. It was Conservative in the sense that while women were given aliyot, the Hebrew liturgy never changed. I would stand every week on Shabbat morning not believing in this “Lord,” “God,” “King.” When I couldn’t bear the patriarchal imagery anymore, I began rewriting words and phrases in my head. This was in the early 1980s.

I was also teaching at the Havurah Institute in the early ‘80s, and one year a well-known male leader asked me to write kavanot (meditations) for the Havdalah blessings. I blurted out, “I can’t do that because I don’t say those blessings anymore.” To which he replied rather cavalierly, “So write your own blessings.” I was more than a little nervous to do that, but I went home that night and wrote my first blessings. The audience—men and women—was very encouraging.

Since this is the 20th anniversary edition of “The Book of Blessings,” what has changed and what has stayed the same?

The book includes a new preface in which I address meditatively and poetically issues that have been brought up by readers over the years. For this edition, my publisher—Central Conference of American Rabbis Press of Reform Judaism—asked four rabbis in the movement to write essays about how they felt the book had influenced Jewish liturgy in America and Israel. I’m very moved that many communities in Israel have picked the book up. Israelis are very particular about their Hebrew and so I’m thrilled the prayers and poems speak to them.

Can you address the theology behind your beautiful prayers?

I feel very strongly about the immanence of the sacred. The sacred is within us and within all of creation, and it is our task to bring it forward through our actions. Blessings don’t just acknowledge a sacred moment; they bring it about.

In “The Book of Blessings ” I sometimes use the word “divine” in Hebrew and English as a substitute for “God” because it is non-personal—that is, not anthropomorphic. But when my son and I collaborated on creating his bar mitzvah service, he told me he didn’t relate to the word “divine.” I suppose it was too close to a traditional theology for him. At that point in time, he was more “radical” than I!

Since the High Holidays are approaching, how can “The Book of Blessings” supplement the machzor?

The machzor deals with themes of the season, which are largely about life and death. There’s some of that in “The Book of Blessings,” particularly in a section entitled “Sustaining Life, Embracing Death.” But the book of mine that is specifically intended to enrich the High Holidays is called “The Days Between: Blessings, Poems, and Directions of the Heart for the Jewish High Holiday Season.” That book contains a substantial Yizkor service based on the original liturgy. I call the recreated service Ezkor—“I recall.” I also re-envision the Un’taneh Tokef. In both books, I build upon the themes of the original liturgy or the structure, which is why I think my work can be considered traditional.

In the new preface to “The Book of Blessings” you write, “It is my hope that this book may offer theists and nontheists alike a place where their hearts may speak.” Can you elaborate on that statement?

In the new preface, I also write: “Is it possible that direct address of a transcendent deity is not the only kind of authentically Jewish prayer? For me, prayer is a reaching inward and outward at once—inward to the core of my self, to feelings, thoughts and an ineffable sense of being-ness. And outward, to my participation in something much larger than my self—the greater self, the greater whole, within which are a myriad of beings who share the need for, and right to love and respect, justice and dignity, sustenance and security.”

In the end, I want a more inclusive community. Many of the people I know and I meet don’t believe in God and I want to give them an alternative. I’m hoping that my poetry and blessings are open enough that people can read themselves and their visions of faith into it. That’s what I mean by theology. I wanted the book to speak to theists and nontheists, and even those who call themselves atheists. On Yom Kippur I’ll be sharing my poetry and blessings with a Humanist congregation.

You are also an artist. How do you marry word to image?

Since adolescence, I have wanted to combine my artwork with my poetry. Recently, in my work as a painter, I re-envisioned the traditional art form of the mizrach (“east” in Hebrew), which is a plaque to be hung on a wall of the home, indicating the direction to face in prayer. The plaque contains the word “mizrach,” sometimes accompanied by biblical verses, and it usually has beautiful illumination and decoration. My recreated mizrach does not point to a geographical east but rather to an “inner east,” to the prayer of the heart. In it there is a dialogue between my poetry—I consider my blessings poetry—and my art.