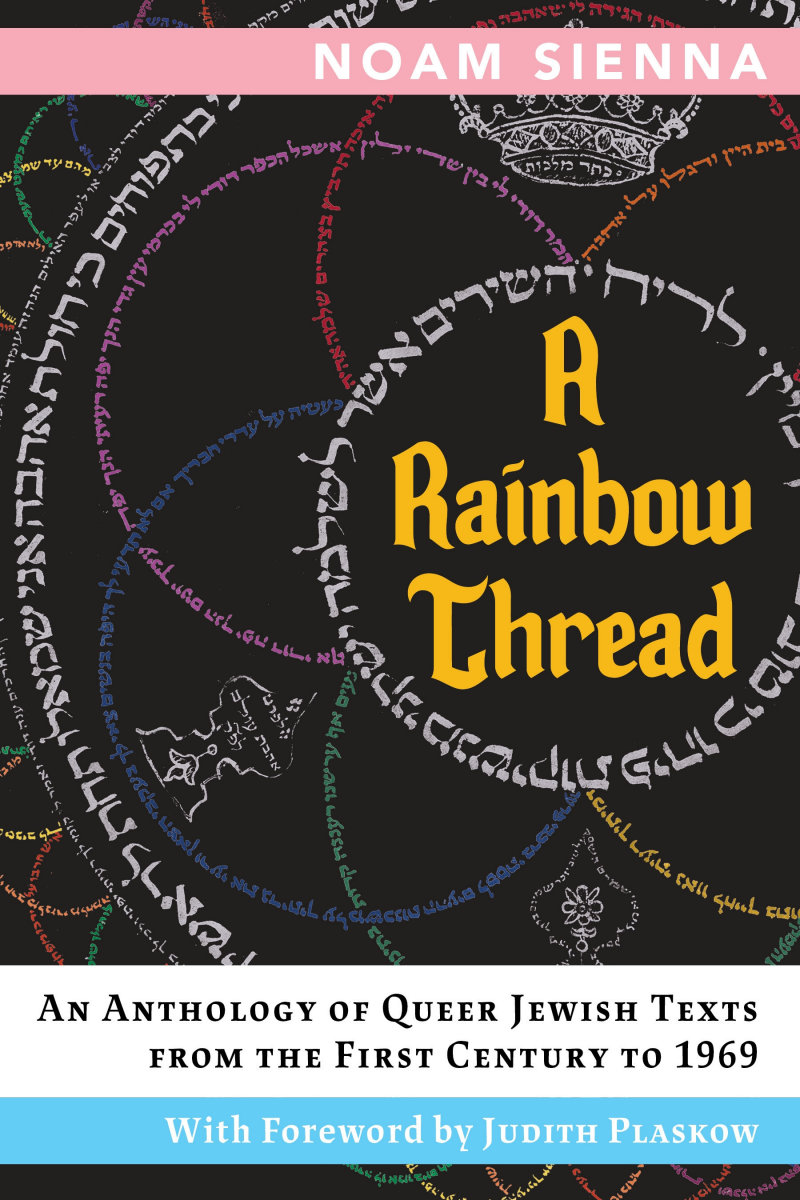

Collecting Jewish LGBTQ texts that span over two millennia, “A Rainbow Thread: An Anthology of Queer Jewish Texts from the First Century to 1969,” is an ambitious project edited by Noam Sienna. Sienna, a 2011 Brandeis University graduate, recently received his Ph.D. in Jewish history from the University of Minnesota. Through “A Rainbow Thread,” Sienna intended for the 120 texts representing a total of 16 languages to illuminate rabbinic texts, poetry, prose and Talmudic passages on gender and sexuality.

The dynamic, encyclopedic-like book presents a spectrum of works that have been translated into English for the first time. Sienna was intent that most of the translators identify as members of the LGBTQ Jewish community. The range was challenging, but Sienna found queer and trans Jews who were fluent in everything from Italian to Catalan.

The Lambda Literary Foundation—the primary LGBTQ literary association in North America—honored Sienna’s outstanding edition with a 2020 Lambda Literary Award for LGBTQ Anthology. Additionally, the Association of Jewish Libraries selected “A Rainbow Thread” for its 2020 Judaica Reference Award.

Sienna recently spoke to JewishBoston about the challenge of compiling the anthology and how he wished a book like his had existed for him in middle school.

Your anthology draws from a wide range of Jewish cultures reflected in the number of translators you have. What was your criteria in selecting the texts?

It was a case-by-case situation. There were two stages. The first stage was, “Would I consider the text for inclusion in the book?” To qualify, it had to fit somewhere in the intersection of everything relating to LGBTQ identity, including gender and sexuality. It also includes moving between genders, across genders and outside of gender, and it includes romantic, erotic, sexual encounters or expression between people of the same sex. On the other hand, I considered anything that had to do with the broad picture of Jews and Jewish culture, and that included texts written by Jews and texts written about Jews.

Then came the hard part: narrowing down what was going into the book. For that, my criteria were: the text had to be rich enough and accessible enough on its own that somebody could read and appreciate it without a lot of background—texts that had some kind of a story, texts that were vivid, texts that were engaging and texts that were surprising. The texts that did those things rose to the top of the pile.

I also wanted to make sure that a diversity of voices was represented in terms of gender. I wanted to include women’s voices, trans and non-binary voices, and texts written in different geographical locations. Jews don’t just come from Europe, and Jews don’t just live in the United States.

You had to stop somewhere, but why did you stop collecting texts at 1969?

The Stonewall uprising happened in 1969. That moment in the summer of 1969 is often pointed to as the beginning of modern LGBTQ history. It served as a catalyst for a whole new wave of activism and public discourse. People started talking about sexuality and gender almost immediately after 1969. That was true even in the Jewish world.

Diving into the actual texts, one of the first ones that intrigued me in the book was about Abraham and Sarah. They were thought of as tumtumin—not clearly identified as man or woman—which, the sages say, may have accounted for their infertility problems. Can you speak to that text?

It is a fascinating text and it’s so important to me because this is not a new discovery. This text is in the Talmud. It’s been there all these years. But we haven’t looked at it with the lens of thinking about how this might resonate with the experience of trans and intersex and non-binary people today. This text is using the technique of the midrash to expand our understanding of our story and our ancestors. Abraham and Sarah were tumtumin, which is a category that emerges in the rabbinic period to distinguish people who are neither clearly male nor female.

That’s what Jewish education and Jewish community are about. It’s finding a place to see yourself as part of the tradition, as part of the heritage. You are the latest in this long line of what it’s meant to figure out what it is to be Jewish. [As a queer young man], I was looking for a place in the Jewish community and tradition to plug in. But I didn’t find the place that matched all of my prongs. I could fit one prong in here, or I could fit one prong in there, but I didn’t have the whole socket. And putting these kinds of texts all together in this book opens that space for people, especially young people, to recognize themselves in the tradition.

What’s the best way to approach this anthology?

I’ll point people to the very back of the book. There’s a set of what I call menus, or tracks, that I’ve grouped by genre. For example, you might say, I want to understand how gender and sexuality have been treated in halakha—in Jewish law. You can go to the halakha track and start with those. You can track the conversation within Jewish law that has talked about gender and sexuality, starting from Talmud through to the 20th century. If you want to hear the voices of LGBTQ Jews in poetry and literature, there’s a poetry track and a literature track. There are tracks by identity. For example, you can explore what it meant to be a Jewish woman, maybe a Jewish woman who loves women from antiquity to the present.

“A Rainbow Thread” is a reference book to which a reader can keep returning, right?

My goal in writing this book was to give it to myself when I was in middle school and looking for what it meant to come into my identity. I hope the book will be available in middle school libraries, family bookshelves, high school libraries and rabbis’ bookshelves around the country.

This interview has been edited and condensed.