Rachael Cerrotti’s destiny was set when the writer, journalist and documentarian insisted that her bat mitzvah Torah portion had to be Lech L’cha from Genesis. Abraham’s mission “to go forth” is also alternatively interpreted as “go to yourself.” Both translations highlight Cerrotti’s determination to bring her grandmother Hana Dubova’s Holocaust story to light. Cerrotti had help from Hana, a prolific and consistent writer, who kept journals for 70 years.

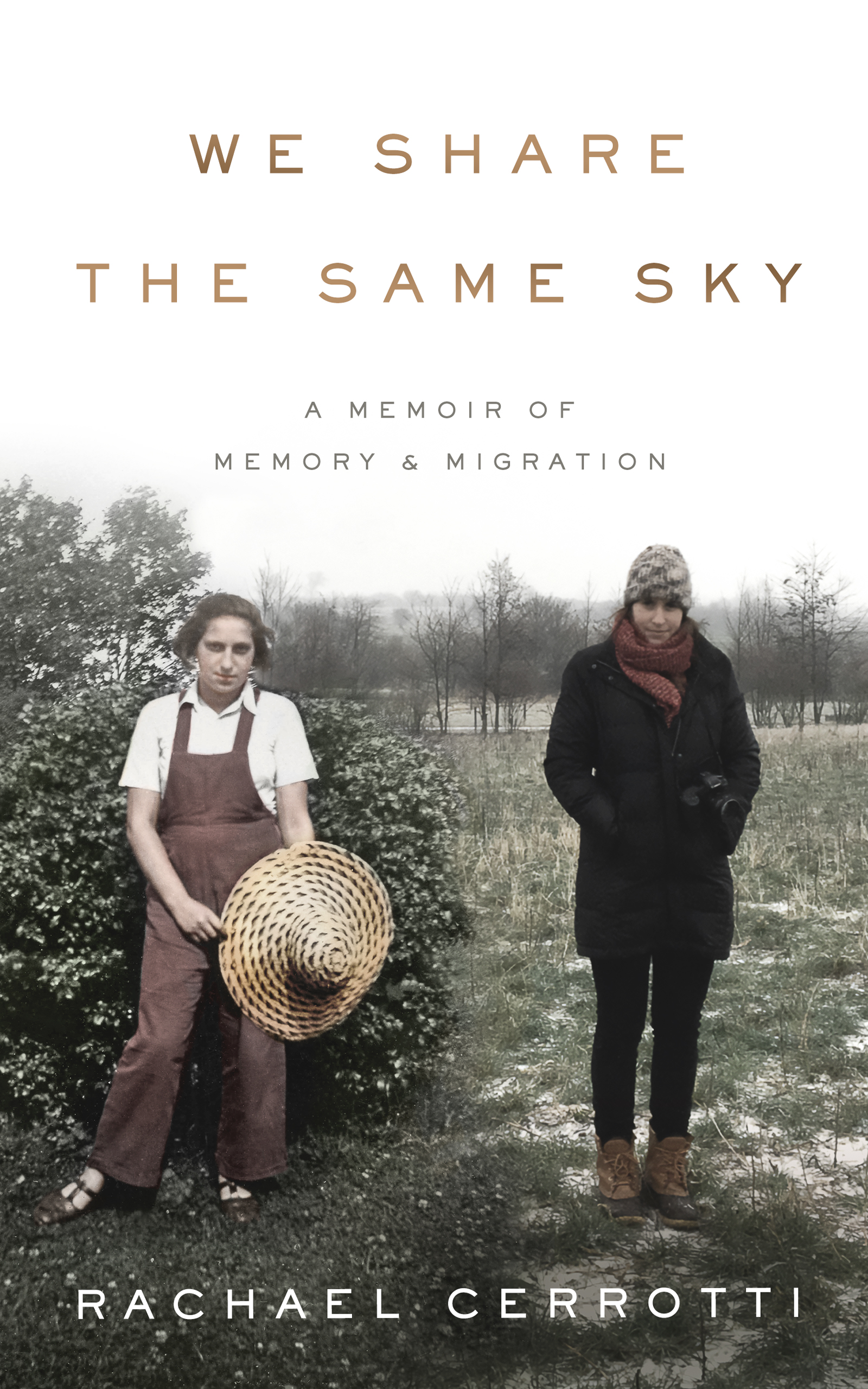

This serendipitous and miraculous gift enabled Cerrotti to embark on a decade-long undertaking to retrace her grandmother’s multi-layered story of survival in the Holocaust. The result is a compelling new book called “We Share the Same Sky: A Memoir of Memory & Migration.” Cerrotti also previously hosted a related podcast of the same name.

Now 32, Cerrotti traveled to Denmark, where her grandmother found refuge from Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia in 1940 when she was 14 years old. “Hers is a very unique story,” said Cerrotti. “I describe it as a story of light in a very dark history. I’m using ‘light’ very loosely. She was her family’s sole survivor.” Hana was saved by the Danish people and survived a dramatic escape to Sweden in which she and other Danish Jews almost drowned crossing the Baltic Sea into Sweden.

Related

While Cerrotti’s travels brought her to Denmark, Sweden, the Czech Republic and Poland, it was in Israel where she met Sergiusz (pronounced Sergio), whom she eventually married. A Polish Catholic, Sergiusz took his first trip to Israel with his parents at 18 and was mesmerized. He returned a few years later as a student. “Sergiusz was gifted at languages, and he studied Hebrew and Israeli politics, which is why he spent his study abroad year in Jerusalem,” Cerrotti said.

Sergiusz and his parents provided logistical and emotional support the year Cerrotti spent in Europe. The young couple eventually moved to Boston, Cerrotti’s hometown, but returned to Denmark to marry on the farm where Hana had lived as a refugee. Cerrotti befriended the children and grandchildren of Hana’s rescuers and they became extended family to her and Sergiusz.

Cerrotti and Sergiusz’s happiness was tragically cut short when Sergiusz died suddenly of an undiagnosed heart condition. Cerrotti was 27 years old. As she grieved in her parents’ Boston suburban home, she also threw herself into telling Hana’s story. She eventually went to work for the Shoah Foundation, where she is currently the inaugural storyteller-in-residence. She also co-hosts a new podcast, “The Memory Generation,” that came out earlier this year. “We dig into what it means to inherit memory,” she said. “We think about it from a technological point of view as well as a personal point of view that we feature in interviews.”

Cerrotti recently spoke to JewishBoston about her new book, Holocaust history and the deep friendships she forged recreating Hana’s Holocaust journey.

You write that Hana’s life story was “the fabric of our family, the tablecloth used for every meal.” Will you elaborate on that observation?

I grew up in a family where the Holocaust was spoken about, where it wasn’t hidden. A lot of families grow up with pasts that are swept under the table. The history of the Holocaust or my grandmother’s refugee status and statelessness was just this fact. It was this thing that was present. Her house had photographs and pictures of an oil painting of her mother. There were photographs of Prague and paperweights from her world travels. My grandmother lived with her life around her, and in that sense, having the tablecloth with a meal is as if they were sitting there with us. I don’t think I was even cognizant of that as a child, but you grow up and look back on your childhood and realize that was much more profound than I could pick up on at the time.

Hana kept a journal all of her life, leaving you a precious gift, a wealth of material.

Memory has become a question mark here because when we write to ourselves, we tell ourselves the same stories differently depending on the day. You see that reflected in someone’s diary, particularly when they’re reflecting on or experiencing a traumatic event. There was one entry in the diary she had later in her life where she talked about being in China. She remembered standing in line somewhere and she writes in her diary about how it gave her a flashback of standing in line with her father to get her Gestapo identification papers in 1939.

You literally walked in your grandmother’s footsteps to recreate her Holocaust journey. What motivated you?

For a long time, nobody understood what I was doing. So, it’s good that this book is finally coming out, so people understand. I think the podcast was the first step in understanding what I was trying to do and the book will help that. My mother was the middle child, and she carried her mother’s history in a much heavier way than her siblings. My dad also loves his family history and spends a lot of time researching it. The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.

I was young when I started this deep dive into the world of Holocaust stories and Holocaust history. There’s an argument to be made that maybe I was still too young to really grasp the gravity of it all. So I’m eager for the day I get to go back to Kolin in the Czech Republic and think about it a little bit differently as someone now immersed in all types of testimony, not just my grandmother’s. I have studied this history for over a decade.

My generation also inherits some responsibility because we don’t have as much of an emotional burden. Initially, I thought I was going to travel for a year, and then when the refugee crisis broke out and politics started to shift, I felt it would have been irresponsible for me to end the story there. I had emotional distance, but not so much that I didn’t feel deeply connected and it didn’t feel deeply personal. Antisemitism feels deeply personal to this day. I felt that I had to use that personal connection as a motivating factor for the part of tikkun olam I want to leave for the world. In my grandmother’s case, it was figuring out how to tell the story that connected to today. I don’t think my mom would have been able to do that. She’s too close to it.

Your trip to the Czech Republic was traumatic for your mother. But for you it felt redemptive. Bearing that in mind, you wrote that the second generation of Holocaust survivors carries the grief of their parents’ generation. Can you elaborate on that?

My mother’s reflections have certainly influenced how I think about things and the lens through which I look at the Holocaust. But it’s also different for me. And I will also say that I understand my family’s dynamic is different than people who survived Auschwitz. It’s a very different trauma. And with my grandmother’s story, we have all these beautiful connections that have come out of this horrific past, and there’s something very redemptive about these connections. The best gift a traumatic past could give you is these connections as well as the resilience and the community that it can foster.

Denmark is a very special place for you. You were married there and your Danish friends are now your extended family. Can you talk about the importance of Denmark for your grandmother and Denmark’s rescue of its Jewish citizens?

I have a connection to Denmark through my dad’s side of the family. But it did not become a place I really loved and cherished until I was into this project. Then there is the role Denmark plays in my grandmother’s survival story. The country is responsible for her survival twice over. Had she not been welcomed in 1939 in this program with the Zionist movement, she would have been deported to the extermination camps just like her younger brother and parents were. Then you have the rescue of the Danish Jews, which I think is perhaps one of the most important war stories of World War II. This perhaps is just my lens as a third generation [survivor]. But we need a blueprint for how to do right in a world that seemingly is doing wrong. And Denmark offers us that blueprint, at least at this moment in history.

How did Sergiusz contribute to your ongoing reconstruction of Hana’s life during the Holocaust?

If it were not for him, I would not have been able to stay in Europe for a year. That’s not why we were together but it certainly helped the cause on both of our ends. I wanted to come to Europe for a while, and he wanted me to come to Europe for a while. Before we started dating, I thought I would go to Europe for three months. And then it was extended to six months. And then when we started dating it became a year. I had this home base with him. Emotionally the project would have felt differently to me if I didn’t have someone to miss. If I were a single, mid-20s woman traveling around Europe, I probably would have had different conversations and relationships. He helped me sustain energy for this with his interest in the story. And he was always so incredibly supportive without ever making me feel guilty for leaving. I would leave for chunks at a time to go on these adventures. He was never envious. There was nothing but pure support and excitement on my behalf.

Where does the book’s title come from?

It comes from Sergisuz’s mother, Danuta. The project initially had a different name. But as soon as she said to me that no matter how far we are from each other, “We all share the same sky,” I knew that was the book’s title. Danuta and I say that to each other all the time. I was texting with her the other day and telling her how much I wish she could be here with me as I promote the book. And she said, “Well, we still share the same sky, and it’s become our way.”

Find information about Rachael Cerrotti’s speaking events and book tour here.