When Deborah Feinstein, founding chair of the Hebrew College Arts Initiative, was charged with selecting Israeli art from the college’s permanent collection, she saw a grouping of works donated by Nitza Rosovsky, an Israeli-born author, editor and a member of the Hebrew College Board of Overseers. Called “Works on Paper” when the collection was first shown at Hebrew College, it reflected two distinct periods in Israel’s history of art—New Horizons and a move toward abstraction in 1970s when the country was staking out its place in the art world.

In an interview with JewishBoston, Feinstein said she intuited that these two intervals of time in Israel’s art world evoked the idea of syncopation. “Many of the works in the show started as consciously using abstraction in personal expressions of the founding of the state,” she said. “Life in Israel was difficult in the 1940s, and moving into the 1970s, war loomed. Historically and artistically, these time intervals tied into the concept of syncopation, hence the show’s title, ‘Syncopation.’”

Feinstein’s challenge was to locate the beats and therefore bring forward the rhythms inherent in these works of “lyrical abstractions.” The result was the expression of a unique musicality. As acclaimed painter Joshua Meyer observed, “The way Deb built the show is like notes on a page of music.”

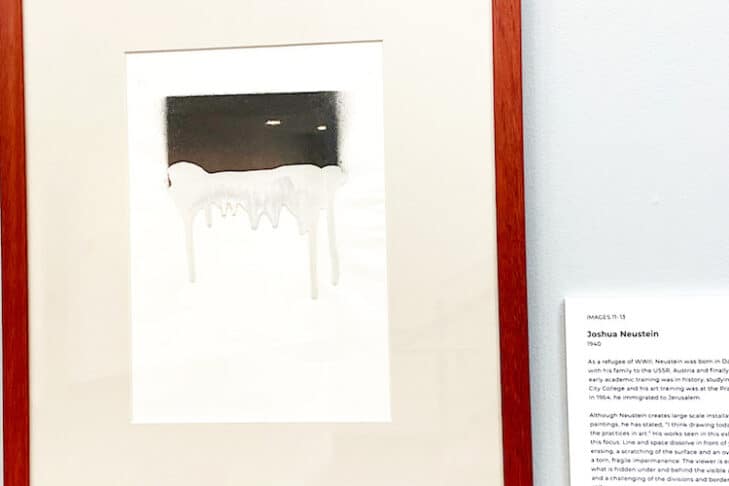

Meyer generously guided me through the exhibition, whose scope and ambition spoke volumes. He pointed out the critical influence of Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky, about whom Feinstein wrote in an essay introducing the show. Feinstein “described his work as ‘musical compositions’ with an ‘inner resonance’ in which the color touches the soul itself. The combinations of colors produce vibrational frequencies, akin to chords on a piano.”

Meyer recalled studying art in Israel. He remembered feeling at the time that he was “seeing European art through the lens of Israelis. Now,” he said, “I see these artists pushing their work in new directions. And these works demonstrate that there’s still a search for identity embedded in their message. The key question is, what does it mean for these immigrant artists to build a land and a relationship with the country? And how do they make art that is Israeli?”

As we explored the exhibit, we noticed these diverse works of art were having a hushed conversation with each other, and other artists worldwide. For example, we paused at Rita Alima’s work. Alima was born in Haifa in 1932. Her use of color reminded Meyer of the British artist David Hockney. Yet Meyer was cautious in offering definitive interpretations of the art, particularly when the artists worked in a complicated place like Israel.

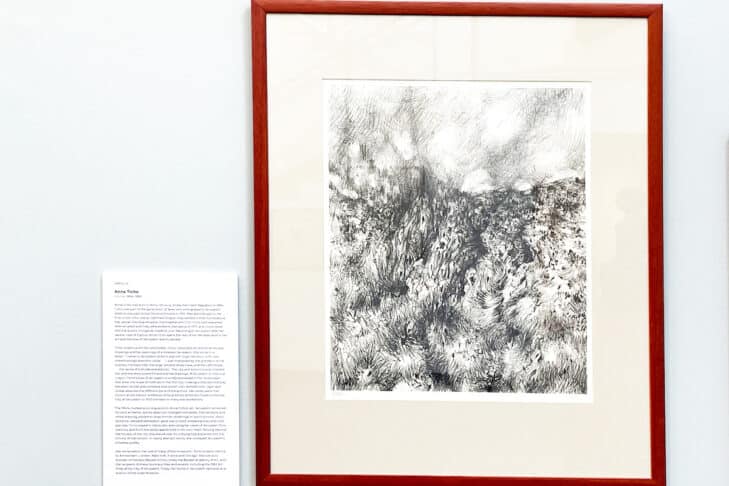

Anna Ticho was born in 1894 in what is now the Czech Republic. She followed her Zionist dreams and settled in Jerusalem early in the 20th century. As Feinstein explains in her curator’s notes, Ticho became known for her “windswept, inexorably terrestrial landscape drawings and her paintings of a timeless Jerusalem.” Feinstein quoted a letter Ticho wrote: “I came to Jerusalem when it was still ‘virgin territory’ with vast, breathtakingly beautiful vistas…I was impressed by the grandeur of the scenery, the bare hills, the large ancient olive trees and the cleft slopes…a sense of solitude and eternity.”

According to Meyer, Ticho’s works in “Syncopation” are a notable contrast to the light touch for which she was known. “Some of the darkness is from Ticho’s hand, and some of it is the picture itself and where it hangs in proximity to other works,” said Meyer.

Displayed strategically close to Ticho’s work, Tova Berlinski’s art carries its own heaviness. Berlinski was born in Oświęcim, Poland (future site of the Auschwitz concentration camps), in 1915. The oldest of six children, she grew up in a Hasidic household before she moved with her husband to Palestine in 1938. Berlinski left behind her Hasidic upbringing and began to paint at age 38. According to a New York Times article in 2017, quoted in the curator notes, “Berlinski’s early works are careful abstract landscapes, full of light, but her art shifted in the 1970s to portray the pain of the Holocaust.” Meyer noted that shift and observed that much of her later work can feel haunted.

Moshe Hoffmann was born in Budapest in 1938 and lived in Red Cross buildings and then Budapest’s Jewish ghetto for the duration of the war. He and his family immigrated to Israel shortly after the Holocaust. Hoffman worked as a woodcut artist and was also a sculptor, painter and poet. Feinstein’s notes assert that Hoffman’s work “moved abstraction toward an intensely personal approach. In this exhibit, his landscapes provoke another tone. The viewpoint is skewed—the landscape pulls one down.”

In one of Hoffman’s paintings, chaos is rendered in window shutters randomly opened and twisted, and in crooked patios and terraces. All of the objects are encircled in what appears to be barbed wire. However, when ambiguity takes over, one can see the artist painted a vine. Meyer observed: “It’s as if you’re on a balcony looking out at a landscape, and the hills in the distance with vines coming through. But the piece is also steeped in Hoffman’s personal history and feels like barbed wire.”

George Chemeche was born in Basra, Iraq in 1934, and immigrated to Israel in 1949. He is the only Mizrahi artist in the exhibition. Feinstein’s notes observed: “His style is intimately associated with pattern painting, sensuous, decorative and romantic. His early works tended toward figurative displays; however, as he matured, Chemeche accentuated the flat plane, two-dimensional surface…[In his later work, he created] designs that could evoke memories, desires or dreams.” To that end, his piece in the show presents writing in Arabic, Hebrew and English to capture rhythm.

“It was an honor to do an exhibition for Israel and show the wide stance of Israeli art, creativity and ingenuity,” Feinstein said. “As these works in the exhibition move across the surface of the wall, there is a crescendo of energy. Excitement is generated as the whole vibrates to a climax. There is a syncopated interaction of voices.”

“Syncopation: Lyrical Abstraction in Israeli Art (1970s)” is on display at Hebrew College through Nov. 30, 2022. Plan your visit.