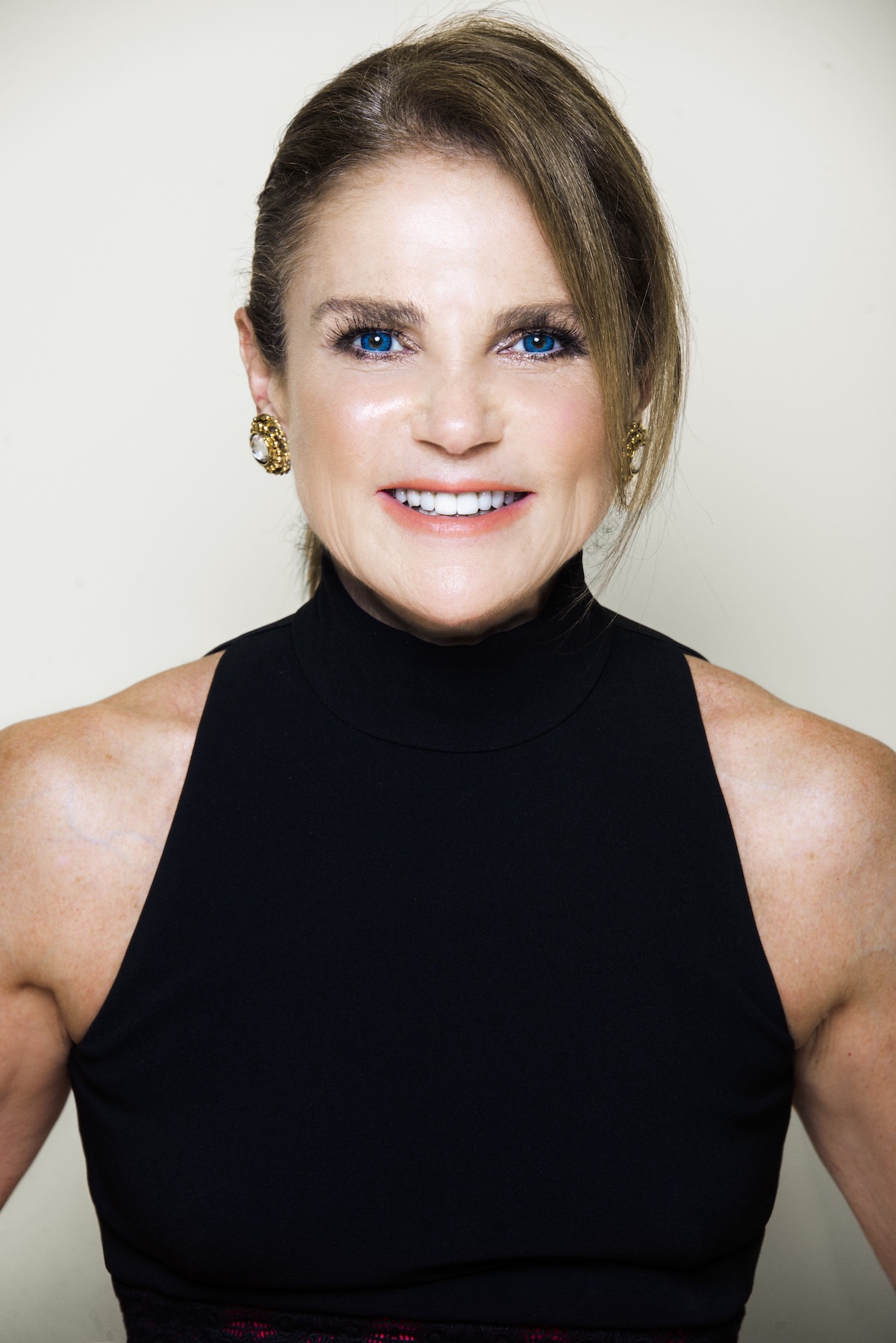

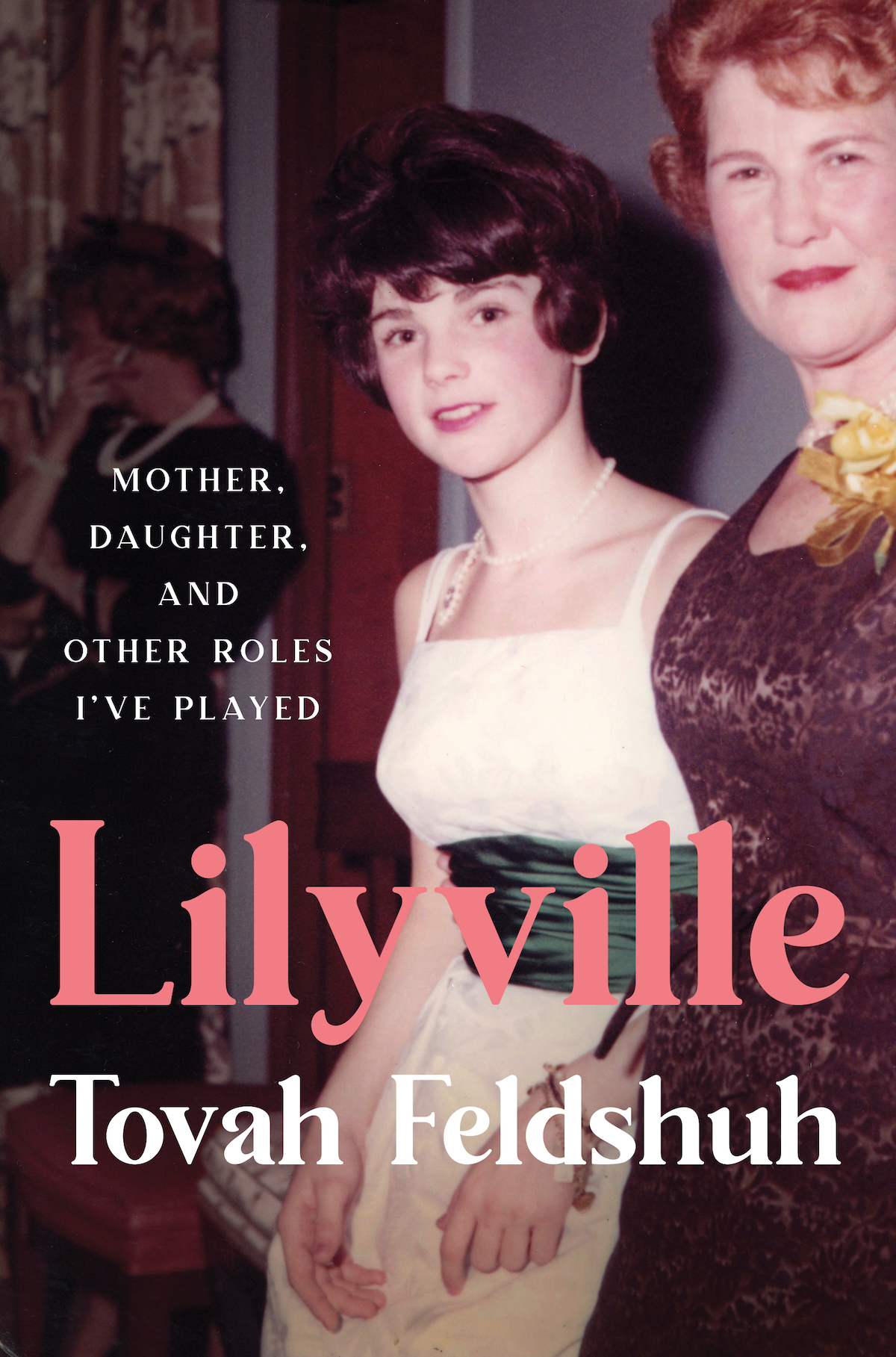

The curtain goes up on Lilyville, and six-time Tony Award and Emmy Award nominee Tovah Feldshuh steps out as its funny, witty and memorable tour guide. Lilyville is a life, a state of mind and, as Feldshuh points out, a metaphor for grit and resilience. It is also the title of her fabulous new memoir, “Lilyville: Mother, Daughter, and Other Roles I’ve Played.” The book is an affecting, voice-driven chronicle of Feldshuh’s evolving relationship with her strong, inimitable mother, Lillian Kaplan Feldshuh.

True to Feldshuh’s deep roots in the theater, she structures her book as three acts complete with an overture, post-performance bows and a cast party that stands in as the book’s acknowledgments. But this book belongs to Lily even as Tovah plays iconic Jewish women, including Prime Minister Golda Meir, Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and now Dr. Ruth Westheimer. She said she brought a bit of Lily to each of those portrayals.

Feldshuh recently spoke to JewishBoston about her 50-year acting career, her Scarsdale childhood and her greatest role of all as Lily’s daughter. Lillian Kaplan was born in 1911 on a dining room table in the Bronx. Feldshuh noted that her mother, born before women’s suffrage, lived through the roaring ‘20s, the Great Depression, World War II and beyond. “I cover 110 years of Jewish women’s history as it combines with the American dream,” she said. “And through it all, my mother reigned supreme in Lilyville for better or for exasperation.”

Feldshuh recalled that the first time she told Lily she wanted to be an actor, her mother calmly instructed her “to go to the kitchen, get my challah knife, stick it in my heart and twist.” Despite her mother’s outsized reaction, Feldshuh persisted, and when the time came to go to college, she floated the idea of applying to The Juilliard School. “You’re not going to a trade school,” snapped Lily. Feldshuh did not venture far from Scarsdale and attended Sarah Lawrence College. She studied philosophy and cut her professional teeth acting on the weekends in New York City.

Despite Lily’s opposition to her daughter becoming an actor, Feldshuh recalled that Lily fostered her love of theater in many ways. Both she and her older brother have had successful careers in theater. She described the silence of her childhood home in Scarsdale—one that echoed her mother’s silence—as her first motivation to act. “When I was a young child, I talked to the bathroom mirror,” she said. “I made up little songs and characters and eventually toured my show to the living room. My father, who was very clear about his unconditional love, applauded, and my mother only said ‘very nice’ with her arms folded across her chest.”

By the end of college, she changed her name from her given one—Terri Sue—to her Hebrew name, Tovah. Lily was not happy. “She told me, ‘We didn’t come to this country to call yourself Tovah. You already have an unpronounceable last name, and now the whole name is unpronounceable,’” said Feldshuh. However, the name stuck after a boyfriend, who was not Jewish, “found great beauty in the name and didn’t have the Jewish bias of it not being too Jewish. This was the 1950s. McCarthyism was rampant, and the Rosenbergs were executed. Americans were terrified of Russia, so to have a name that resonated with the pogroms of Russia and also reflected the new state of Israel was to undo Lily’s American dream.”

Nevertheless, Feldshuh said that changing her name “altered the landscape of my artistic life. I was perceived as Jewish, Orthodox, Israeli and an expert in Judaism. But the name helped me land on the marquee when I played Yentl. The name ended up bringing me great luck, and it was an early pathway to my small contribution to repair the world—tikkun olam. It also helped me bring to life other Jewish heroines—I saw the different facets of womanhood as it was cloaked in the robe of Judaism.”

Feldshuh almost passed up one of her more famous roles playing Golda Meir, which she initially saw as another Jewish mother role. But she worked with playwright William Gibson of “The Miracle Worker” to change “Golda’s Balcony” into a more immediate and experiential piece of theater. “You’re right inside the experience of the 1973 Yom Kippur War,” Feldshuh said. “Golda then boomerangs into that caustic experience and her memory. She flips in the play as she speaks about pogroms, falling in love with Morris and the birth of her children. Playing Golda was an example of a part that asked me to transform along with it.” Feldshuh movingly recalled that she traced Meir’s journey from New York to Milwaukee to Denver and eventually to Israel. She also went to Kyiv and Pinsk, where Meir experienced pogroms.

Her research and tenacity resulted in “Golda’s Balcony” earning the distinction as the longest one-woman show in Broadway history. As for Lily’s appraisal of the play and Feldshuh’s performance, she said: “I rate your parts by how you look. Dolly Levi was a 10; Golda was a zero.” Add into the mix Lily’s reaction to Feldshuh’s role as the flying grandmother Berthe in “Pippin,” where she sang on a flying trapeze: “Tovah, why do you still have to earn a living like this, and on a trapeze yet?”

Feldshuh’s relationship with her indomitable mother pivoted when her beloved father, Sidney, died. Feldshuh was 40, and Lily was close to 80 years old. She said that shortly after the funeral, Lily turned to her and asked, “How much longer are you going to blame me?” Feldshuh replied, “Not another minute.” What had been “a great generational chasm” between mother and daughter began to close. The woman who never told her daughter she loved her was suddenly affectionate. Feldshuh took meticulous care of Lily in the last act of her mother’s life. She took her on international trips and even secured a small part for her in “A Walk on the Moon.” “Once my father died, I gave her things like celebrations to look forward to,” Feldshuh said. “All of the holiday gatherings like break-fast and seders were in her large house in Scarsdale.”

Feldshuh, now the mother of two and grandmother of three, said she channeled some of Lily’s spirit in her own mothering. “In Judaism, we not only love our children, we name them after our honored dead,” she said. “It’s all about l’dor v’dor—from generation to generation—as we hand down the crucial values of the Jewish religion and its ethos.”

As for her third act, Feldshuh has a number of upcoming projects. Next month she plays Dr. Ruth Westheimer in “Becoming Dr. Ruth.” The play will be filmed in California (get tickets here) and have a limited in-person run at the Bay Street Theater in Sag Harbor, New York (get tickets here). She is slated to play Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 2022 and is in talks about turning “Lilyville” into a television series, for which she hopes to play herself and Lily.

“Lilyville,” she noted, “is a metaphor that communicates how the third act of your life can be the crowning glory of your wit and wisdom and participation on this earth. Lily set that example as she blossomed in the last part of her life. I want to make this time the crowning glory of my artistic and familial contributions.”

Tovah Feldshuh will be in conversation with Jewish Women’s Archive CEO Judith Rosenbaum on Thursday, May 27, at 8 p.m. Register here.