On Nov. 16, the Jewish Arts Collaborative presents the American premiere of a play, “You Will Not Play Wagner,” written by the late South African playwright Victor Gordon, who adapted his play for this video format (and sadly died during the COVID epidemic). The play deals with a specifically Jewish problem: Is it permissible, especially in Israel, to play the music of the German composer Richard Wagner, a vitriolic antisemite who is also one of the most famous and revered musical minds of all time. The plot plays on some actual history: an unofficial ban on playing Wagner in Israel and the controversies and passions raised by Wagner the man and the symbol after the Holocaust.

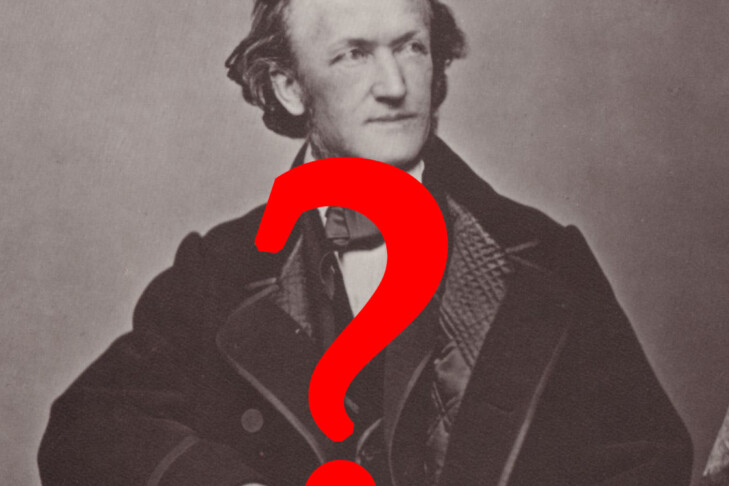

Richard Wagner (1813-1883) was brilliant, groundbreaking and visionary—one of the most influential and important composers of the 19th century, considered by many the most influential figure in the history of music; his impact extended not just to music, but all the arts. He was also openly antisemitic, xenophobic and ethnonationalist. Wagner the man, and his legacy, both good and bad, continue to this day. The historian Nicholas Vazsonyi wrote: “There is no path into the twentieth century—for good or evil—that bypasses Wagner.”

Yes, Wagner was an antisemite. His 1850 essay, “Jewishness in Music,” is a scurrilous diatribe against Jews and Jewish culture in general, and against Jewish composers. Originally issued under a pseudonym, he later expanded and reissued it under his own name in 1869. The essays attack “Jewishness” in German art, fault the Jews for being “alien” and “separate,” and denigrate Jewish appearance, behavior and especially their music; he claims that Jews had no art of their own, that they corrupted “holy” German art. His solution: Jews should abandon their Judaism and assimilate. Wagner wrote more similar essays, but despite consternation, responses and even embarrassment in some quarters, the impact was dwarfed by the popularity of his operas and music. Four days after his death in 1883, the Boston Symphony scrapped a planned program to present a Wagner Night. Orchestras across the U.S. and Europe played tributes. The opera festival of his music that Wagner began in Bayreuth, Germany, in 1876 continued to draw great crowds (and does to this day). Pilgrimages were made to his grave at his Bayreuth villa, including one Bostonian Isabella Stewart Gardner, who took a leaf from the ivy that covered his grave and pressed it in her scrapbook. She had previously attended the festival. Following the Metropolitan Opera’s 1903 production of “Parsifal,” the famed Yiddish actor-singer Boris Thomashefsky (grandfather of conductor Michael Tilson Thomas) produced a Yiddish-language version of “Parsifal” in New York. The rise of the Nazis changed much. Hitler heard his music as a young man, attended concerts at Bayreuth when in power and befriended the Wagner family. Wagner became a Nazi folk icon. Until 1929, the Nazis made great use of his music for rituals, rallies and assemblies. Yet not all were enamored. Goebbels opposed playing “Parsifal,” feeling there was too much Christian symbolism in it. What worked for the Nazis was Wagner’s association with German “Volk-culture” and myths the operas invoked. Indeed, Wagner’s popularity in Nazi Germany’s artistic life declined somewhat during the war. While some have associated Wagner’s music with the Nazi death camps, there are only a very few instances described by survivors of his music being played in them, preferring popular and dance music of the day, and light classical. But the connection between the Nazis and Wagner is indelible and cannot be ignored. Wagner, however, is complicated. Consider: Wagner was a German, and violent German antisemitism existed long before he was born—it is a common thread in the culture of not just Germanic peoples but as far back as the Romans. Rhineland persecutions of Jews in Germany date back to 1096; indeed, antisemitism was prevalent throughout Europe for centuries. Wagner was a product of the prevailing German culture. But that does not excuse him. Oddly enough, Wagner had several Jewish friends. The poet Heinrich Heine was a friend and Wagner praised him in “Jewishness in Music.” Wagner chose a Jewish conductor to premiere “Parsifal”—Hermann Levi, leader of the Bavarian Court Opera, descended from a long line of German rabbis. Wagner actually asked Levi to be baptized; he refused. Even so, as Ross relates, Levi continued conducting “Parsifal” at Bayreuth for many years, even having kosher food prepared for his father when he attended. Angelo Neumann, a Jewish impresario, arranged for a touring production of the “Ring” operas. Among the artists that revered, wrote about or modeled some of his artistic ideas are E.M. Forster, Willa Cather, Emile Zola, architect Louis Sullivan, Virginia Woolf, Paul Cezanne, Thomas Mann, JRR Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Salvador Dali, Van Gogh, Poet Sidney Lanier and many, many others. Even more interesting are two icons that one would not think would be “Wagnerites”: W.E.B. DuBois and Theodore Herzl, the Zionist “spiritual father of the Jewish state.” Du Bois saw the myths in Wagner’s operas as inspiration for developing a new kind of African American imagination of the past and a spirit for a future. Studying in Germany in 1936, he attended concerts and operas, and was moved seeing the “Ring” cycle in Bayreuth. He did comment negatively on German antisemitism in a travel column he wrote—but also noted that he felt less prejudice as a Black man in Germany than in the U.S. As a reporter in France in 1891, Herzl began work on his manifesto, “The Jewish State,” and attended a dress rehearsal of “Tannhauser,” which inspired him with ideas of redemption for the Jews. As he wrote in his autobiography, he worked on the manifesto every day “until I was completely exhausted; my only rest was listening to Wagner’s music, particularly to ‘Tannhauser,’ an opera that I went to hear as often as it was given. Only on the evenings when no opera was performed did I doubt the rightness of my ideas.” At the Second Zionist Congress in Basel in 1898, music from “Tannhauser” was played. If two seminal thinkers and activists like Herzl and Du Bois can find inspiration in Wagner, and countless other artists as well, where does that leave us today? Is it possible to separate the man from his music? There is an informal ban on playing Wagner in Israel. In 1981, Zubin Mehta, conductor of the Israel Philharmonic, announced at a concert that the orchestra would play music from “Tristan” as an encore and that anyone who preferred not to hear it could leave. It produced a ruckus, even fist fights, but most of the audience actually applauded. In 1991, conductor Daniel Barenboim, a Jewish conductor who programmed Wagner elsewhere, planned, then canceled, a concert in Tel Aviv; in a 2001 concert in Jerusalem, he asked the audience’s permission to play the “Tristan” prelude as an encore. A debate ensued, but the cheers won out and he played it. Wagner’s impact on music and art was profound. His operas continually play across the world. His musical techniques anticipated and paved the way for 20th-century music. The ubiquitous “Here Comes the Bride” is the Bridal March from Wagner’s “Lohengrin.” His music is used in the soundtrack of dozens of movies. He was an odious personality, but a musical genius. If we play his music, are we giving in to the man—or by playing it, do WE triumph over him? Victor Gordon’s play brings the passions and problems to the fore, as a young Israeli conductor in an international competition held in Israel tells the organizers he will play Wagner in the finals. The founding patron, a Holocaust survivor living in New York, wants to prevent it. Watch the play and consider yourself: Would you play Wagner? “You Will Not Play Wagner” is an original virtual play created by JArts TheaterWorks, directed and produced by Lilila Levitina and starring Annette Miller, Avi Hoffman and Ofek Cohen. Get tickets for Nov. 16 at 7 p.m. here.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here.

MORE

Related