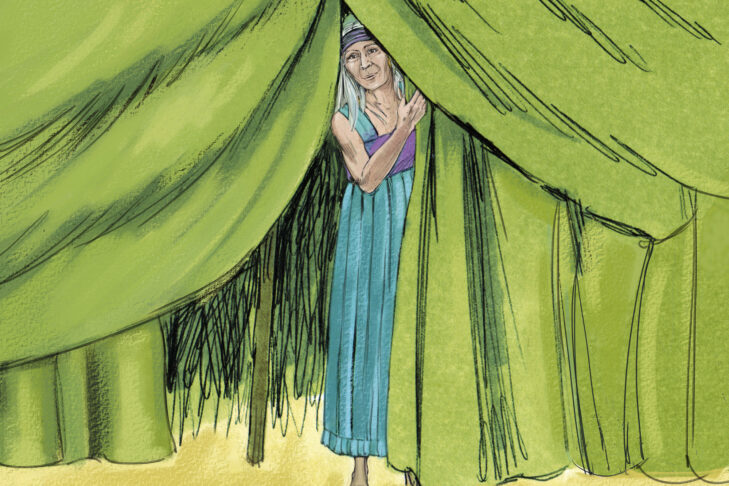

God walks into the tent of a 99-year-old man and declares: “A year from now, your 90-year-old wife will give birth to a child.” The 90-year-old woman, ear pressed against the tent flap, spontaneously erupts into laughter.

A few scenes later, we read—ה׳ פקד את שרה, God remembered, tended to Sarah, and she gave birth to Isaac.

But I want to rewind to that previous scene. A year ago. Ninety-year-old Sarah eavesdropping. The mysterious visitors reveal to her husband that in a year—despite their advanced years—they will become parents. Sarah loses it. Shakes with laughter. A few moments later, God inquires: “Why did Sarah laugh?” Ashamed, Sarah attempts to deny it: “What do you mean? I didn’t laugh.” לא, כי צחקת. “But you did laugh,” God replies.

God’s question hangs in the air: Why does Sarah laugh? What is the quality, the timbre of her laughter? The laconic Torah text leaves it wide open.

If the Talmudic rabbis were to direct the film version of this scene, here’s what it would look like: Sarah, bent and bitter, hardened and full of despair at what life has denied her, cranes her neck to hear the whispering behind the tent flap. Then comes this “fake news” of a promising future. She laughs. If you could call it that, for in this scenario, it’s more like a resentful “hah” or “pfff” or even a snort. It’s an, “Oh, please, tell me another one”—a cynical, non-verbal rejection. The Sarah of the rabbis’ film is a dyed-in-the-wool pessimist. Like any good pessimist, she knows the end of the story. And it doesn’t end well for her. There is no possibility of joy, and thus her laugh is one of confirmed cynicism, of despair.

That’s one version of the film. But there’s another take, inspired by our teacher Dr. Aviva Zornberg’s reading of Ramban: Yes, 90-year-old Sarah has despaired from years of unfulfilled promises, but she presses her ear to the tent with curiosity; she hears the stranger utter these absurd words—they don’t even make sense:

שׁוֹב אָשׁוּב אֵלֶיךָ כָּעֵת חַיָּה, וְהִנֵּה-בֵן, לְשָׂרָה אִשְׁתֶּךָ

I will certainly return to you in a year’s time, and behold, your wife Sarah will have a son.

Something bursts within Sarah; for a second, she lets go of the despair she knows to be true and sees a picture of this unfathomable possibility and, in that moment, a pure, contagious laughter swells in her. Perhaps you have experienced this kind of laughter It’s uncontrollable. It overtakes you from the inside out. There is an absurdity and a free fall, a what if? Could you imagine? This is not the laughter of controlled certainty, of cynicism and despair from the other scene—this is the laughter of uncertainty, of not knowing the end of the story and imagining what kind of wild turns it could take. It is the seed of hope planted within an unpredictable future. Hope born of imagination, of what if my world can stretch beyond my perceived limitations? What if I can exceed what I thought I was capable of?

For Aviva Zornberg, it is this moment of imagination and possibility, of embracing uncertainty and not knowing the end—aka hope, that ignites the laughter, and it’s this laughter that makes Sarah fruitful. The laughter conceives Isaac—and gives him his name. It transforms Sarah from a withered secondary character incapable, by her own account, of experiencing pleasure, into the complicated matriarch we read about today.

I heard wise words from a wise rabbi a few weeks ago—on this question of hope and knowing the end. She said: “Our behavior changes when we have hope, when we believe redemption is possible….It’s a kind of spiritual resistance.” We had just returned from a trip to the West Bank and East Jerusalem, where I was facilitating an Encounter tour for a group of Jewish executives, rabbis and lay leaders, and this rabbi spoke of two scenarios—similar to our two scenes with Sarah. If I return to my community after this trip with nothing but despair and hopelessness—which is, mind you, a reasonable response to what we saw. If I think I know the end of the story, and it’s a tragic one, then I have an easy job. I can sit there in my armchair clicking my tongue and furrowing my brow and watching my despairing predictions come to pass daily on any number of news outlets.

But what if I return from this trip and say this future is not foretold; it holds multiple possibilities. We’re in a dark and dangerous place in history. But I can’t know the end of the story, and I choose to believe that redemption is possible, that transformation, forgiveness, dare we say peace—as laughable as it might seem—is in the realm of possibility. I open my imagination to hope, and when I choose that hope, my behavior changes. I put myself on the line. No longer sitting, despairing in my armchair. Rebecca Solnit writes in her book “Hope in the Dark”: “Hope locates itself in the premises that we don’t know what will happen and that in the spaciousness of uncertainty is room to act.”

I pray for the spiritual resistance to enter each day with a sense that redemption is possible, a sense of hope, a sense that the ofek, the horizon out there, no matter how far, is reachable and requires that I get to work.

But the uncertainty of it all is terrifying. How much easier to be like the despairing Sarah of the first scenario—to know the end, predict how things will fade—to at least have some clarity amidst chaos. Solnit writes: “Hope is the story of uncertainty…which is more demanding than despair and…more frightening. And immeasurably more rewarding.”

As we read this week of Sarah, Abraham and Hagar, I want you to remember the Sarah of a year before. Not the despondent one, but the Sarah courageous enough to hope. For those of us feeling more kinship with the defeated, bitter Sarah right now, cynical Sarah who knows how things end, I want to invite all of us to audition for the other Sarah, the one who practices the spiritual resistance of hope, whose peels of laughter embrace uncertainty, suss out possibility within impossible situations, and whose laughter births new worlds.

Jessica Kate Meyer serves as rabbi-chazzan at The Kitchen in San Francisco. Formerly, she was rabbi at Romemu in New York City. Ordained by the Hebrew College Rabbinical School in 2014, she is an alumna of the Wexner Graduate Fellowship.

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishBoston assumes no responsibility for them. Want to add your voice to the conversation? Publish your own post here. MORE