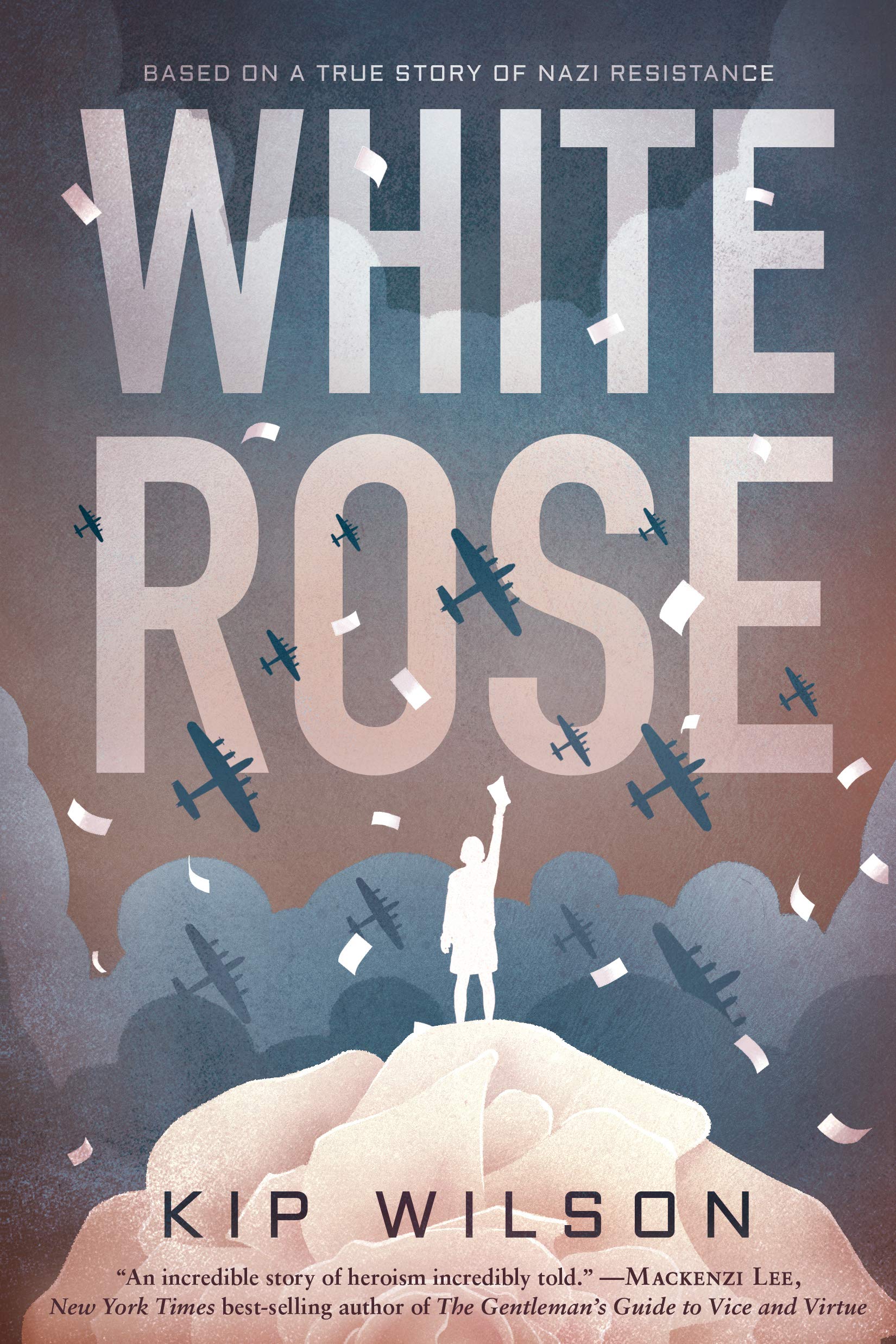

In 1943, sister and brother Sophie and Hans Scholl, as well as their friend Christoph Probst, were beheaded for distributing pamphlets that criticized the Nazi regime. The young trio had founded a resistance movement called the “White Rose.” A newly published book of the same name by Kip Wilson tells the group’s story from Sophie’s point of view. Wilson charts the course of Sophie’s life from her comfortable upbringing, where, like her friends, she belonged to a Nazi youth group, to becoming the brave resistance fighter who gave her life in opposition to the Nazis.

“White Rose” is also distinctive for telling Sophie’s story in verse. It abandons chronology in favor of a more complicated structure that jumps between the SS interrogation of Sophie to her backstory. Casting the story in poetry is an inspired choice. For example, there is the affecting trope of Sophie’s beating heart throughout the story. Boom, boom, boom thumps her heart as she distributes anti-Nazi literature or is undergoing intense questioning and imprisonment.

In the end, the book compels readers to look inward and ask: What would I have done as a German citizen in Nazi Germany? Would I have laid my life on the line for my moral ideals?

In anticipation of Yom HaShoah, Wilson spoke to JewishBoston about writing her unique book and Sophie Scholl’s short yet inspiring life.

When did you first learn about the White Rose movement?

I first heard about the White Rose movement in the 1980s in my high school German class. I was so fascinated by these people who stood up for others. It was an incredible thing to do at the time. These kids decided that the adults around them were doing nothing to fight the Nazis. As a teenager, that resonated so deeply with me. I’ve been incubating this story since 1984.

The first book about the Scholls and their movement came out in the 1950s, and it was by their sister. There was a movie in 1980. But their story became better known when more archives about them were opened up in Berlin in the late 1990s. There was more information available about their trial. I consulted the family archives in Munich, which mostly comprises letters and diaries. I loved seeing Sophie’s handwriting firsthand and experiencing her artwork. She loved nature and pressed flowers in her letters.

Why isn’t the White Rose movement as well-known as other episodes of Holocaust history?

There hasn’t been a lot translated about the White Rose movement. There was a book by a sister of the Scholls, and one biography about them, published in the 1980s, was translated into English. Without translations, things get lost. There are also the practical considerations that before students learn about White Rose they need to read “The Diary of Anne Frank.” They need to be exposed to the works of Elie Wiesel. However, the White Rose story is a helpful one to know given that hate is on the rise in this country. It’s important to have this example of somebody not marginalized but standing up for people who were. I feel like this is Sophie’s moment. Youth activism is contributing to awareness regarding climate change, gun control and other issues.

What moved you to tell the story through Sophie?

I originally had more points of view in the book. I first told the story through Sophie, Hans and Christoph. My editor suggested that it might be stronger to focus solely on Sophie. When I first heard about the White Rose movement, Sophie drew me in. Sophie was the youngest member of the group, as well as a female in a very male world. She was doing very brave things in this male world. I do miss Hans and Christoph as main speakers; their stories are just as absorbing. But it was the right thing to do to focus on Sophie. To have more than one perspective, they have to be distinct, and all of the people in this group had similar outlooks and ideas.

Why did you choose to tell the story in verse?

I studied German literature and focused on poetry. I wrote my Ph.D. dissertation on Rainer Maria Rilke. Before the idea came to me to tell this story in verse, I considered myself a prose writer. But I’m also the poetry editor of a literary journal, and in that role, I talk to poets all the time. It occurred to me that verse is suited for tragic and emotional subjects. The white space on the page helps to balance the heaviness and gives the reader a chance to breathe.

I attempted to write about the White Rose movement in prose in the early 2000s, and it was a struggle. Writing in verse felt natural and opened up vistas for me. I encourage anyone who is interested in writing to try different forms. You never know what feels right until you try.

The structure of your book alternates between the current story and the backstory. How did you decide to tell Sophie’s story this way?

The first draft was even more unconventional, in that I wrote it in reverse. I started with the executions and went backward in time. Anyone who looks up Sophie and the White Rose movement will know about the executions. My beta readers said that reading the book in reverse was confusing. But I didn’t think that straightforward timing was going to work either. One of my favorite books is “All the Light We Cannot See” by Anthony Doerr, and it uses two timelines. I love the way it pulls all the pieces together. Things fell into place in his book, and ultimately mine, with the timeline working that way.

How do you think Sophie’s story will resonate with teens and adults?

I hope the story will resonate with both groups. The book aligns with sixth and eighth-grade curriculums. Twelve seems like the ideal age to be introduced to the story. Older kids can identify with the protagonists and become inspired to take action against hate. There is a crossover element to the book—adults can get a lot out of it and talk to teens about it.