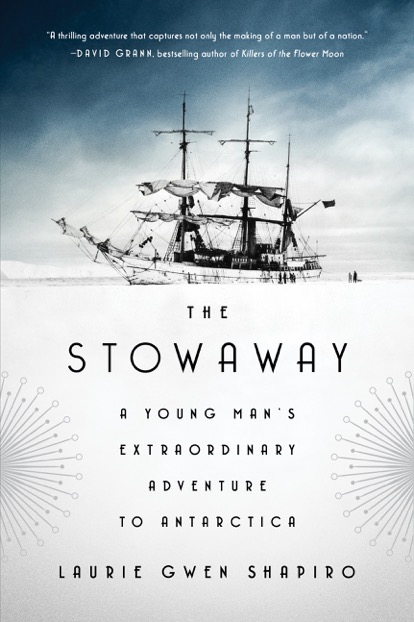

Laurie Gwen Shapiro tells the story of Billy Gawronski, a stowaway who was the youngest member of Admiral Richard E. Byrd’s expedition to Antarctica in 1928.

How did you come upon this story?

I’ve written novels as well as made documentaries. My first novel was a very fun, light novel I wrote in my late ‘20s. Like a lot of young women in the ‘90s, I was pushed into writing chick lit, but I never felt it was my area. I also have a concurrent film career in which I’ve tackled serious, big stories. These were two different divides. I thought if I could write a documentary as a book, I’d be in a better place.

I took a short assignment to write about a Polish Catholic Church on the Lower East Side where I live. When I was researching, I found a small article online that reported that 500 kids marched from the church to City Hall to greet a Polish kid named Billy Gawronski, who stowed away to Antarctica. It also said the kid swam across the Hudson River to stow away. I knew I had to find out more about this story.

How did you piece the story together?

I had the caffeinated idea that people did not spell the name “Gawronski” correctly in the articles I read. I tried all sorts of spellings and started to get more hits. I also went to the library and found a few more articles about Billy. But the documentarian in me thought that I needed to talk to a descendant for the story.

I made the craziest Excel chart with all the Gawronskis I could find and cold-called them. I said, “Hi, I’m a writer. Are you descended from a kid who jumped into the Hudson River and went to Antarctica with Admiral Richard E. Byrd in 1928?” On call No. 16 a woman who had an accent answered the phone. She was in Cape Elizabeth, Maine. The woman was Billy’s second wife, and she said very softly, “I was hoping someone would find me. I have scrapbooks and stories.” At that moment, I suspected this was going to be my story.

What sort of legwork did you do for “The Stowaway”?

I spent a year researching the story, but to own it I needed to go to Antarctica. I needed to see what it looks like, what it smells like, the different colors in the sky. I traveled the same route Admiral Byrd took via New Zealand, which sails through very choppy waters. Then Billy’s wife led me to his son, who was in a maximum-security prison in Florida.

How did your background come into play as you researched and wrote the book?

I’m from the Lower East Side, and because I’m Jewish I brought things to the story that no one else might have. For example, Billy was a “Shabbos goy” who spoke Yiddish and German. Later in his life he was a captain in the Merchant Marines and he was on ships with Holocaust survivors coming out of Germany. He could speak to them in Yiddish and German.

Benjamin Roth was one of the airplane mechanics on the trip, and there was tremendous anti-Semitism toward him on the expedition. When I looked him up in the Jewish press, I learned that he conducted the first Passover seder in Antarctica.

Billy was not the only stowaway. There were other stowaways who were Jewish and black. All of this may seem like a random story, but it makes sense to me. I was looking to bring my skills as a novelist, documentarian and a mother to the project.

The story had a certain kismet for me and it ended up changing my career significantly. Like Billy, who was supposed to go into the upholstery business with his father, I didn’t want to be pigeonholed either. In my case it was as a chick lit novelist. It’s especially important for women not to be passive about their careers. Because I steered my ship, I got a second chance at a literary career.

Why was the public so taken with Billy’s story?

This was a time when no one knew what was going on in Antarctica. It was almost like going to the moon. Admiral Byrd was bringing airplanes on the expedition. It was the new modern age of exploration, and over 60,000 people applied for 70 spots on the boat. The Rockefellers and Vanderbilts wanted their kids to go. The idea that a 17-year-old boy—a first-generation immigrant—applied and was eventually accepted to the expedition was appealing to a lot of people. Billy tried to stowaway four times. There’s a folk-hero quality to that. New Yorkers loved him, and his story went wider than New York. A lot of Americans followed him, and his story even went international. Billy wanted to escape his pre-determined future so badly. That’s something that appeals to all of us.

How have readers responded to the story?

I received a letter from someone who had been a sailor on one of Billy’s ships during the Second World War and said that Billy read poetry to his crew. There was also a letter from a gentleman on Billy’s Murmansk, Russia, runs as a merchant marine. And there was a very poetic letter from a man who never met Billy but related to him. He wrote: “I didn’t know Billy personally, but wish that I had. Certainly, through your effort, I can tell myself that even us old folks can discover some of the heroics that lurk in our own lives.”

The fact is that this young man willed himself into becoming a part of history. In realizing that, I used all of my experiences and skills from the past to write this book. Frank McCourt was my high school English teacher, and I had his voice in my head as I was writing. He said it was important not to coast. You have to keep pushing yourself, and you have to try harder.

Laurie Gwen Shapiro will be in conversation with culture reporter Judy Bolton-Fasman at Newtonville Books on Thursday, March 22, at 7 p.m. For more information, click here.