In a recent talk at Harvard Law School, Corine Wegener described her cultural heritage preservation work as “Monuments Men, Part II.” Indeed, Wegener’s past and present efforts in Iraq and elsewhere invite comparison with the World War II rescuers of cultural property looted by the Nazis, as dramatized in the 2014 George Clooney-Matt Damon movie.

While serving in Iraq with the U.S. military during the Iraq War from 2003 to 2004, Wegener assisted with the response to the looting of the Iraq Museum in Baghdad, and helped preserve the Iraqi Jewish Archive, a collection of artifacts related to the Jewish community of Iraq, found in the headquarters of Saddam Hussein’s secret police.

Wegener’s Sept. 15 talk at Harvard focused on her more recent work for the Smithsonian Institute, where she serves as director of the Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative. As she explained, she is helping Iraqis document possible war crimes after the liberation of parts of their country from ISIS. Wegener is also helping with cultural preservation endeavors in civil war-torn Syria.

Saving the Iraqi Jewish Archive

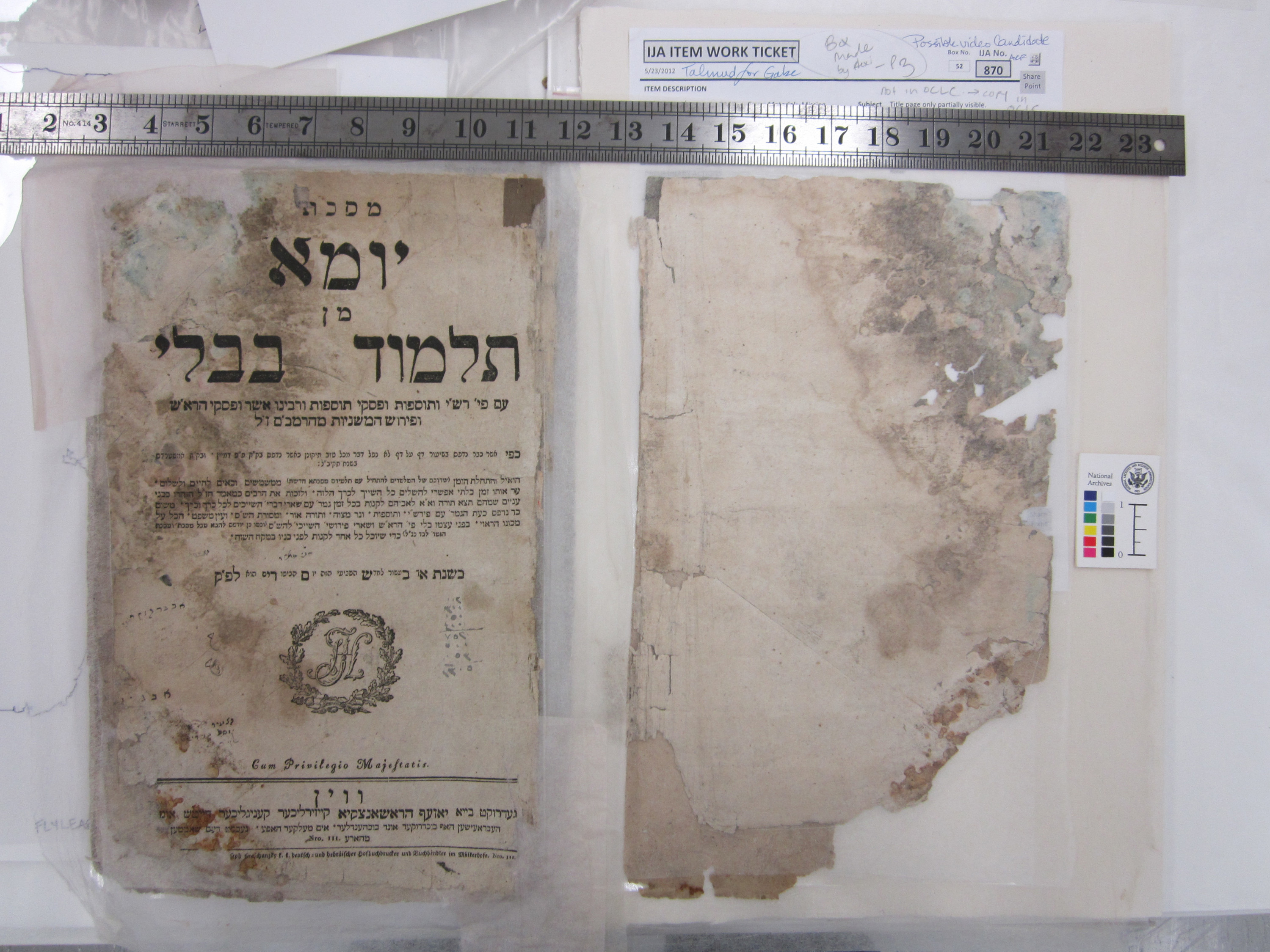

Sixteen years ago, while in Iraq as a civil affairs arts, monuments and archives officer, Wegener was contacted by the Coalition Provisional Authority, which governed Iraq after Hussein’s fall. A collection of materials related to the Jewish community of Iraq—including 2,700 books, along with tens of thousands of documents—had been found in the basement of Hussein’s secret police headquarters. Wegener is not Jewish, but she has experience as a curator of a Judaica gallery from her past work for the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

As Wegener explained, the Iraqi Jewish community has origins related to the Babylonian exile. Once, she said, Baghdad had been 20% Jewish. But modern-day exile, emigration and loss of property have diminished the current community, which Wegener said numbers “probably less than a dozen.”

As for the “archive,” it did not qualify as such in the traditional sense, Wegener explained. Its contents had not been compiled using traditional methodology for scientific purposes—rather, they had been “looted, removed from synagogues and schools,” she said. “It always kind of gave me a chill.”

Meanwhile, there were problems with its physical state. The basement was flooded. The weather was hot. The collection had to be stored elsewhere, in metal boxes, and kept frozen.

“Nearly every day, the whole summer of 2003, I went in and out of a freezer truck to check on the boxes,” Wegener recalled. “I would open them and worry about the mold problem. I couldn’t keep them frozen at the low temperature I wanted.”

Yet the collection was stabilized with help from the National Archives—including a visit from Doris Hamburg, its then-director of preservation programs, and Mary Lynn Ritzenthaler, who heads its conservation laboratory. Shortly before Labor Day 2003, Wegener was the courier who brought the archive to the U.S. for further preservation, on a cargo plane big enough to hold a tank.

The materials have since been digitized and shown around the country in a traveling exhibit.

“The National Archives has an amazing website dedicated to the Iraqi Jewish Archive,” Wegener said. “Tons of materials have all been digitized, with high-resolution photos and documents. It’s really amazing what’s been done, both the preservation effort and the effort to share what’s in the materials with the public.”

Wegener has seen the exhibit multiple times, including when it first went on display at the National Archives from 2013-2014, as well as at the National Archives museum in Kansas City in 2015, and, most recently this year, at the U.S. Army Airborne & Special Operations Museum in Fayetteville, N.C.

Asked what should ultimately be done with the archive, Wegener said, “I don’t know. I’m torn.”

She recalled giving a talk in Kansas City and meeting Iraqi Jews who said, “‘This was related to my grandfather, this letter was from my great-grandfather.’ They’re really very tied [to it] through their identity. Their families were forced to leave Iraq. They have a stake in the heritage.” On the other hand, she said, “I understand it’s also tied to Iraq; it can’t be separated.” She noted that Iraqis have become sensitive to the importance of cultural heritage in the wake of the destruction caused by ISIS, and that she has trained Iraqis in cultural heritage preservation. But, she said, the fate of the archive is a “tough decision.”

With the Smithsonian

This November marks seven years since Wegener joined the Smithsonian. In this capacity, she is helping Iraq deal with the devastating impact of ISIS.

In her Harvard talk, Wegener showed images of the Mosul Museum in northern Iraq before and after its 2014 occupation by ISIS. Sculptures of lamassu, or Assyrian deities, were vandalized, and the 26,000-volume library was burnt. She and colleagues from the Smithsonian, after receiving training from the FBI, visited the now-liberated museum in February to document evidence of the destruction.

“We literally had only 12 hours to do the whole thing,” Wegener said. “We did the best we could under difficult circumstances.”

Wegener is trying to help Iraq use the 1954 Hague Convention—established in the wake of World War II—as a possible means to prosecute suspects in the destruction of Iraqi cultural heritage.

“We learned from watching war crimes tribunals in the past that try to incorporate cultural heritage,” Wegener said. “There was a recent prosecution of a guy who helped smash some of the saints’ tombs in Mali—not [through the] Hague Convention but the Rome Statute … So far, [similar cases] have not been successfully prosecuted under the 1954 Hague Convention. We want to see if we can change that.”

As she told JewishBoston, “To destroy a people, you have to destroy their heritage. It’s a way to injure whole communities … [We’re] helping people, helping them preserve their identity, their reason for living, to go on.”