Sixty-five years after the Vilna Shul’s first cornerstone was laid in 1919, the shul’s lone parishioner, Mendel Miller, held that era’s last service in the synagogue. That was 1985, and the building at 18 Phillips St., standing squarely between Beacon Hill and the West End, fell into disrepair for a decade.

In the 1990s, initial steps were taken to restore the Vilna Shul. The project was a unique melding of the visionary and actual discoveries on the ground. It was a time when the building was stabilized and attention was paid to the infrastructure. The roof was repaired, windows rebuilt, a sprinkler system installed and the furnace replaced as part of a substantial cleanup of the property. It was another 10 years before the building was habitable.

Once it was safe to occupy the building, the shul took its rightful place as the last of the 57 historic synagogues still standing in Boston. Recouping the shul’s history has been a notable aspect of its ongoing restoration. A valuable piece of that history was uncovered in murals underneath the beige walls of the second-floor vestibule and the sanctuary. Three layers of murals were discovered through more than a decade of careful conservation.

The murals present a window to a fascinating history of synagogue folk art in Eastern Europe. Wall paintings and decorations were a distinct feature in synagogues that were in what is now present-day Belarus, Poland and Lithuania. The Vilna’s recovered murals reflected the various artistic themes and tastes of those razed synagogues of Europe.

Christen Hazel, the Vilna’s director of development, recently walked me through a FaceTime tour of the murals that have been conserved in the sanctuary. “These murals are a treasure for the arts and for Jewish American history,” Hazel explained. “They are the only known Jewish multi-layered folk-art murals in North America.” Although the artist is anonymous, Hazel guesses that at the time, the artist may have also painted murals in Boston’s Metropolitan Theatre, previously known as the Wang Center for the Arts.

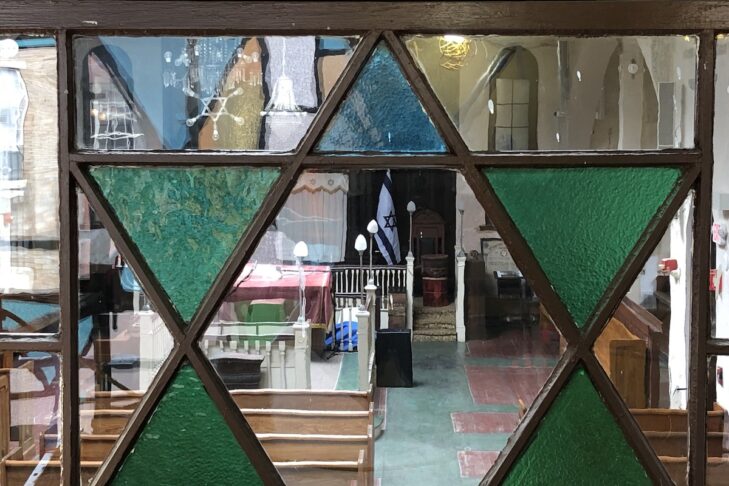

On our first stop at the second-floor vestibule, we pause at a stained-glass window and then go through doors leading to the sanctuary. The space has been repainted a warm mustard-gold color, a close approximation of the original color. Hazel pointed out that a layer of light blue paint originally obscured a mural painted around a lighting fixture on the sanctuary’s ceiling. There are two bands of green and red paint around the edges, which frame a floral pattern of leaves and white and pink flowers. Conservationists found this decorative mural relatively intact.

In addition, a donor recognition wall will be mounted in the space and a painting by the late Boston Jewish artist Hyman Bloom will hang across from it on the opposite wall. Bloom, who attended the Vilna as a child, has had a recent renaissance that included a retrospective in the latter part of 2019 at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Dalit Ballen Horn, the Vilna’s executive director, explained: “The earliest paint scheme [circa 1920] evokes an age of American history when immigrants came to Boston with their traditions and adapted to the new ways of life. Highlighting these images on a wall in the historic sanctuary was a way for this community to create a visual memory of their connection to Am Yisrael, the people of Israel. By adding these murals, the community was drawing a connection between itself and the larger story of Jewish peoplehood that dates back millennia.” Hazel added that the murals are a “metaphorical window into early immigrant life. This unique community called up biblical scenes in America.”

Gianfranco Pocobene, chief conservator on the project, added: “Works of art, whether they are masterworks by artists such as Titian and Rembrandt or the mural decorations at Vilna Shul, have varying artistic purposes, but they are all worthy of preservation. At Vilna, the ceiling and wall decorations are site-specific and portray a significant moment in the foundation of the Vilna Shul and the immigrants who established themselves in America.”

Hazel noted that the second layer of murals is in the tradition of colonial revival stenciling. Small areas of those murals are visible in the first- and second-floor vestibules. The third layer of murals was painted in the art nouveau style comprising yellow, blue and red curlicues, and roses. Those latest murals were painted on a beige wall. Hazel pointed out that some places in the sanctuary were painted over multiple times in various shades of beige.

During this restoration and renovation process, the Vilna has been recognized as “a contributing building in the Beacon Hill National Landmark District” and is a registered museum through the Council of American Jewish Museums. In the last decade, the shul has expanded its focus to become a vibrant center for Jewish arts and culture, collaborating on public art exhibits, hosting tours of the historic building and curating events and workshops focused on Jewish arts and culture.

“The Vilna’s murals were done to remember the past and create a place of beauty for their community here in America,” said Horn. “The Vilna founders were immigrants, and like all American immigrants, created a gathering place for their new lives.”