Jewish British architect and artist Leon Fenster has lived in Beijing for the last five years. During that time, he has pursued a dream project of painting scenes from the Jewish Diaspora. Fenster began his Diaspora series by drawing pictures that have evolved into what has become the newly published “The Beijing Haggadah.”

“The Beijing Haggadah” is also a collaboration with Brookline residents Carol Fishman Cohen and her husband, Stephen M.L. Cohen. It is dedicated to the memory of their son, Michael H.K. Cohen, who took his life a year-and-a-half after he returned from Beijing, where he lived and worked from 2013 to 2016. In a recent email exchange with JewishBoston, the Cohens pointed out that Michael, who wrote and spoke Mandarin fluently, “had a deep appreciation for Chinese language and culture.” That appreciation is resonant throughout the vividly illustrated Haggadah.

Producing “The Beijing Haggadah” began in earnest when the Cohens met Fenster. Stephen and Leon met at a Moishe House International event in London last year, and six months later, Carol met him in Shanghai at a Limmud retreat for Jews living in Beijing and Shanghai.

Carol described her time in Shanghai with Leon as “a series of discussions over a few days in which [Leon and I] got into a deep discussion about the unique Haggadah project Leon had been envisioning for a number of years. After a lot of brainstorming and recognizing how meaningful it would be to dedicate the project to Michael’s memory, and in commemoration of the 40th anniversary of the Kehillat Beijing community, the idea began to take shape.” It was a natural next step for the Cohens to sponsor the Haggadah’s publication.

During Michael’s time in Beijing, he connected with the Jewish community at Kehillat Beijing. He was also active in Moishe House, which was the center of a close group of Jewish young adults in China’s capital city. Fenster, 33, and Cohen, who would have turned 30 last November, met through their involvement in Kehillat and Moishe House. In a recent interview with JewishBoston, Fenster, who recently left Beijing to self-isolate in Taiwan, said, “Michael was a big motivator for this Haggadah. I knew him very well while he was living in Beijing.”

“The Beijing Haggadah” showcases a style that Fenster described as “hyper-textual in the form of chaotic drawings depicting urban life.” To that end, Fenster intends the 150-page Haggadah to serve as “a jumping off point for other cities in the world.” Written in Hebrew, English and Chinese, Fenster noted that adding Chinese to the mix could have been considered proselytizing, and Chinese authorities had to approve the insertion in the Haggadah. “In general,” said Fenster, “the Chinese welcome Jews because we don’t proselytize. But the [Chinese authorities] understood this was a Haggadah for Jews in China and for the Chinese people to learn about Judaism.”

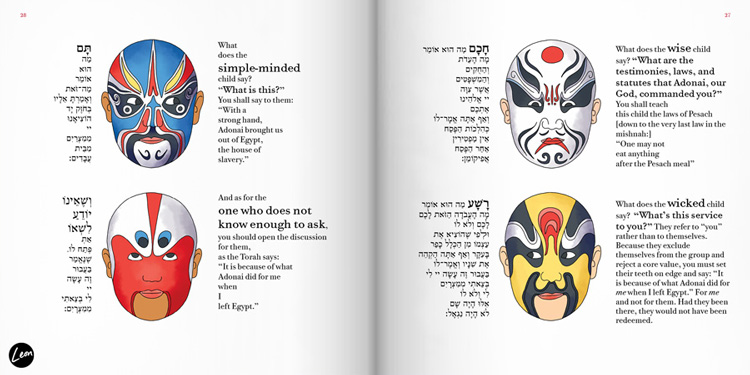

Unlike Shanghai or Hong Kong, which welcomed Jewish refugees during World War II, Beijing’s Jewish history dates back only to 1979. According to Fenster, today’s Beijing community is notably transient with up to 1,500 Jews at a given time living among 20 million other people. Fenster captures the Jewish community’s can-do spirit in pictures that locate Beijing’s landmarks and cultural connotations within the Exodus story. For example, Jews walk through the parted Red Sea dressed in Beijing school uniforms. The Four Children wear Beijing opera masks denoting the traditional designations as wise, simple, wicked and the one who does not know how to ask questions.

One of the Haggadah’s images also shows Michael seated with the founder of Kehillat Beijing and other leaders of the Jewish community. Carol Cohen recalled that during Michael’s last full year in Beijing, he attended three Passover seders. The first night was with his Kehillat Beijing community, the second night was at the home of Kehillat Beijing’s founder and the third evening was a celebratory seder with his friends at Moishe House. Cohen recalled that Michael “sent pictures of each [seder] to us back in Boston, enthusiastically explaining each one.”

Fenster had hoped to debut “The Beijing Haggadah” this year at a seder for up to 600 people in Beijing, but the coronavirus pandemic derailed that plan. Instead, Fenster and the Cohens plan to debut the Haggadah virtually in a series of video calls during the week of March 30. In the meantime, Fenster hopes “The Beijing Haggadah” will present “the idea of l’dor v’dor—to tell the Passover story through the generations as if we left Egypt ourselves—and take it a step further and tell the story in our surroundings. It’s a story that is overlaid into every new place we find ourselves.”

The Cohens anticipate that “The Beijing Haggadah” will inspire people “to appreciate the importance of Jewish community in all its forms and in the most remote places.” In relation to Chinese culture and society, they “hope people look at the Haggadah, understand how it takes Chinese imagery and weaves a story that integrates Hebrew, English and Chinese traditions, and uses it to say something universal about the meaning of Passover and the Jewish experience. And we hope people will remember Michael.”