This summer’s fiction selections reach across the millennia to reimagine a biblical story, score a win for body positivity, become privy to the thoughts of a young Palestinian American grappling with her queer identity, and the consequences of racism and passing in white society.

“The Book of V.” by Anna Solomon

Anna Solomon’s luminous novel is a wholly original and artful recasting of the Purim story; her novel is a stunning, feminist retelling of the Book of Esther. Across the millennia, Solomon braids the stories of three women, including that of the orphaned Esther, and in this rendition the niece of a very creepy Mordechai. Solomon’s narrative moves into the 20th century to take up Vee Kent’s story, the wife of a corrupt U.S. senator looking to get ahead in Washington at her emotional expense. In 2016 there is Lily, a writer not writing and a woman second-guessing herself as a mother to two young girls.

Solomon looked to Michael Cunningham’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “The Hours” and consequently structured “The Book of V.” as a triptych. But as the title implies, this vibrant novel belongs to Queen Vashti. In the Purim story, Vashti is banished and presumably murdered after refusing to dance naked for a drunk King Ahashverus and his courtiers. Vee is the Vashti of the 1970s as she refuses to strip at a party at her husband’s request—a party she has thrown for his political cronies. Lily’s mother, Ruth, another central figure in the novel in very surprising ways, tells her daughter that women can either be Vashti or Esther—“It’s all the same costume, anyway.” Lily herself dismisses the holiday as “lots of drunkenness and misogyny but also female worship, which you could argue is a form of misogyny…there’s also a thwarted genocide of the Jews…it’s a kind of burlesque.”

Solomon’s extended Purim story, and its various iterations, is much more complex and compelling than the Sunday school version. The reader is privy to her characters’ deep, unforgettable interior lives. If Solomon doesn’t take home an armful of major writing prizes for this masterpiece, she will have been robbed.

“You Exist Too Much” by Zaina Arafat

The nameless narrator of Zaina Arafat’s first novel initially appears as a 12-year-old Palestinian American girl who is hounded by town elders in Bethlehem for wearing immodest shorts. In America, the girl’s friends teasingly call her “the terrorist,” the first of many micro-aggressions scattered throughout the vignettes of this powerful book.

It turns out that the narrator is bisexual, anorexic and prone to addiction. Although born in America, she gives off a determinately immigrant vibe that adds to her sense of disorientation and dislocation. Everywhere and nowhere are home to this young woman. Geography and the people she encounters wrench her soul.

This is a novel packed with ideas. But in Arafat’s masterful hands, it is decidedly not a jumble of random thoughts. The narrator stands at the intersection of two cultures, desperate for her homophobic mother’s love. Born in Nablus between two of Israel’s major wars in 1948 and 1967, her mother, Laila, stands between the narrator and her daughter’s sanity.

Readers won’t forget this brilliantly fragmented novel and the young woman who experiences random sexual encounters that leave her addled and addicted to love. At one point, the narrator enters a month-long rehab program. Arafat crafts group therapy scenes that shine a light on the traumas the narrator has internalized and the secrets she has hidden from her family, and ultimately herself. However, in the end, Arafat’s coming-of-age story pivots to show the narrator’s otherness as the foundation of her courage.

“Big Summer” by Jennifer Weiner

A summer reading list is not complete without listing a novel from the incomparable Jennifer Weiner. “Big Summer” is Weiner’s 14th novel and she has yet to disappoint. It’s a shame that Weiner’s work is too often dismissed as “chick lit,” a term that is dismissive and sexist in equal measure. Weiner is an accomplished writer who pens smart, entertaining novels, and this time she’s back and effectively spreading the message of body positivity.

Daphne Berg is a plus-size 20-something woman on the verge of becoming a successful social media influencer. Daphne’s hashtag life is a busy one and a happy one, until her former best friend, Drue Cavanaugh, comes back into her life. Most women have had a Drue in their lives. She’s the cool friend in high school, the gatekeeper to a popular social circle. In Daphne’s case, Drue adopted Daphne as she struggled with her weight. But there’s a price to be paid for Drue’s unexpected attention; she’s the queen bee who manipulates the studious Daphne into writing her term papers. Their relationship comes to a humiliating end when she sets Daphne up with a boy in a bar, and Daphne overhears Drue and the boy fat-shaming her. What happens next is stunning—Daphne stomps on his foot. Someone tapes the incident and it goes viral. Daphne is instantly a feminist hero, and Drue vanishes.

A few years later, Drue is out of friends and begs Daphne to be her maid of honor at her socialite wedding on Cape Cod. Daphne reluctantly agrees, although her roommate and erstwhile high school classmate, Darshi, who knows Drue all too well, warns Daphne about her.

Weiner then straddles genres and the book becomes a rollicking mystery, proving that she is a master at layering her entertaining narrative with plenty of suspense and complexity.

But most impressive is that in Daphne Berg, Weiner has created a self-proclaimed #fiercefatgirl who grows into the more fiercely feminist hashtag #mybodyisnotanapology.

“The Vanishing Half” by Brit Bennett

Brit Bennett’s expansive novel is a multigenerational story that spans half a century. It’s a saga that impressively and thoughtfully takes on thorny issues of racial identity, internecine racism and the corrosiveness of family secrets.

Desiree and Stella Vignes are identical twins from fictional Mallard, Louisiana. The twins’ great-great-great-grandfather founded the town after his white father freed him as his slave. Under his leadership, it came to be a sanctuary for light-skinned Black people. Bennett bluntly writes that “in Mallard nobody married dark.” Over time, the populace’s prejudice against their darker skin brethren deepened, as residents became lighter and lighter “like a cup of coffee steadily diluted with cream.”

When the twins were children, they witnessed their light-skinned father lynched by a mob of white men. As the years wore on, Mallard became a stultifying, traumatic place for the fatherless Vignes twins. Desiree’s fair skin did not save her from a life of poverty. She eventually forced her daughters to quit school to clean white families’ houses in a neighboring town. The girls rebel and run off to New Orleans two hours away. But after a year, “the twins scattered, their lives splitting as evenly as their shared egg. Stella became white and Desiree married the darkest man she could.”

Desiree’s decades-long search for Stella drives the narrative. In the intervening years, each woman has a daughter. Desiree’s daughter, Jude, is “blueblack,” and Stella’s girl, Kennedy, has blonde wavy hair. The girls are not only different in appearance but in temperament. Jude is mature and responsible. Kennedy is spoiled and flighty. The latter is a failed actor, the former a medical student.

Through a series of flukes that occasionally strain verisimilitude, the two young women coincidentally meet in Los Angeles. Stella and her white husband have raised Kennedy in posh Brentwood, and Jude attends UCLA on an athletic scholarship. Despite their different upbringings, these two demonstrate the power of family. And Bennett upholds her compact with the reader, giving us a story of survival and ultimately love.

These non-fiction selections shed light on the Syrian Jewish community in 1980s Queens, introduce Yiddish literature through an eclectic anthology, explore the Sephardic Jewish diaspora through a Greek-Jewish family, and relive the riveting magic of Harry Houdini.

“Lot Six: A Memoir” by David Adjmi

Playwright David Adjmi grew up in the Queens, New York, Syrian Jewish community in the 1970s and ‘80s. His debut memoir, “Lot Six,” which covers those years, reads like great, page-turning fiction. In the book, Adjmi has created a full and vibrant world filled with eccentric family, oddball friends and even memorable therapists. In the center of this world is his mother, a somewhat aloof, unhappy woman, who nevertheless regularly takes her youngest child (Adjmi is by far the youngest of her four children) to plays and museums.

At one point, mother and son venture to “the city” to see “Sweeney Todd,” and the musical leaves a marked impression on young David. “It was like a magic trick: the ugliness was made into something achingly beautiful,” Adjmi writes. He became obsessed with the production and played the soundtrack on an endless loop. For Adjmi, “Sweeney Todd” was the gold standard of theater.

As he navigates his queerness, mental illness and his burden of always being the outsider, Adjmi amply deploys his gifts as a prize-winning playwright. The memoir’s title, “Lot Six,” is retail slang for discount clothes no one wants. The term turns into a metaphor when Adjmi’s family applies it to him.

Adjmi’s vivid portrayals are much deeper and poignant than simply dressing badly or being chosen last in gym class. He unhappily attends a yeshiva and goes on to a public high school, which presents more vexing mysteries like girls. On his first date, he worries about not having “the impulse” to initiate a kiss or a hug with the girl.

Adjmi went on to enroll at USC, where he revels in his “Introduction to Film” class as he is simultaneously discovering West Hollywood’s wild and oftentimes dangerous gay scene. When he had enough of California, Adjmi transfers to Sarah Lawrence College. Back on the East Coast, the search for his authentic self continues in earnest until he realizes he was meant to be a playwright. “Lot Six” makes Adjmi’s literary talent clear to any reader who is lucky enough to pick up this memoir.

“How Yiddish Changed America and America Changed Yiddish” edited by Ilan Stavans and Josh Lambert

This anthology is a deep dive into “the diversity and complexity of American Yiddish culture.” In their preface, the editors encourage readers to experience the anthology as a “grab bag, an opportunity for readers to get a little lost and to discover something that they weren’t expecting.”

The anthology is divided into six sections with delightful titles like, “Eat, Enjoy and Forget” and “Oy! The Children.” Other selections fall under the rubric of politics, American culture and the remix of the Yiddish language. Between 1880 and 1914, almost 2 million Eastern European Jews came to the Western hemisphere. The vast majority of them spoke Yiddish and a number of them settled on New York’s Lower East Side, enduring dire poverty and social ostracism. Stavans and Lambert have carefully curated entries to pay homage to that bygone culture.

Isaac Bashevis Singer’s spirit hovers over these pages. In one edgy entry jointly authored by Stavans, film critic Kenneth Turan, Yiddish Book Center founder Aaron Lansky, writer Rivka Galchen and Yiddish language scholars Janet Hadda and Anita Norich, they consider the Nobel laureate’s legacy. Hadda starkly writes: “[Bashevis Singer] was manipulative, nasty, opportunistic and cynical. Furthermore, he was a sellout; he had sacrificed his Yiddish soul for money and fame in America.”

But there is also a bevy of writers to be discovered. Stavans and Lambert have done a fine job of including a number of women writers, some of whom were new to me. They include poets Malka Heifitz-Tussman and Anna Margolin, and fiction writer Rokhl Korn.

The Holocaust brought on a traumatic change for Yiddish language and culture. Prior to World War II, some 13 million people spoke Yiddish. Estimates place the number of Yiddish speakers today at 400,000. “How Yiddish Changed America and America Changed Yiddish” poignantly showcases that loss.

“Family Papers: A Sephardic Journey Through the Twentieth Century” by Sarah Abrevaya Stein

Sa’adi Levy, the patriarch of the Levy clan of Salonica, Greece, was a prominent printer and editor born in 1820. He perpetuated Sephardic culture by publishing works in Ladino, the Judaized Spanish that the Sephardic diaspora spoke. Sephardic Jews adopted Ladino—a mix of Spanish, Portuguese, Hebrew and other languages—after they were expelled from Spain in 1492. Additionally, Levy published two of Salonica’s popular newspapers. As Sarah Abrevaya Stein writes in her thorough and compelling new book, Levy was a man of his time. He modeled the idea that Ottoman Jews should emulate Western norms while also remaining loyal to the Empire.

Stein then brings readers into the early 20th century, where the most successful of Levy’s 14 children, Dauot, is a high-ranking Ottoman official. By then Salonica had become a vibrant cultural center and Dauot was the de facto head of the Jewish community. This was a city of three faiths, where Jews had a great deal of freedom. By the 1920s, the new Turkish regime had been established and Greeks who lived in Turkey fled to Salonica, changing the city’s character and reducing the Jewish population to less than 20%.

The tragic fate of Salonica’s Jews under Nazi occupation is well known. Most of them perished in Auschwitz. One of Dauot’s sons, Emmanuel Levy, and his family were murdered in the concentration camp. However, many of Sa’adi Levy’s descendants scattered to far-flung places like India, Brazil and Israel. Some also ended up in Britain and the United States.

A historian at UCLA, Stein is a talented researcher. In the course of writing “Family Papers,” she accumulated material related to the Levy family from nine countries on three continents. She’s also a gifted writer who presents a highly specific family history that sheds light on the greater forces that shaped the modern Jewish world.

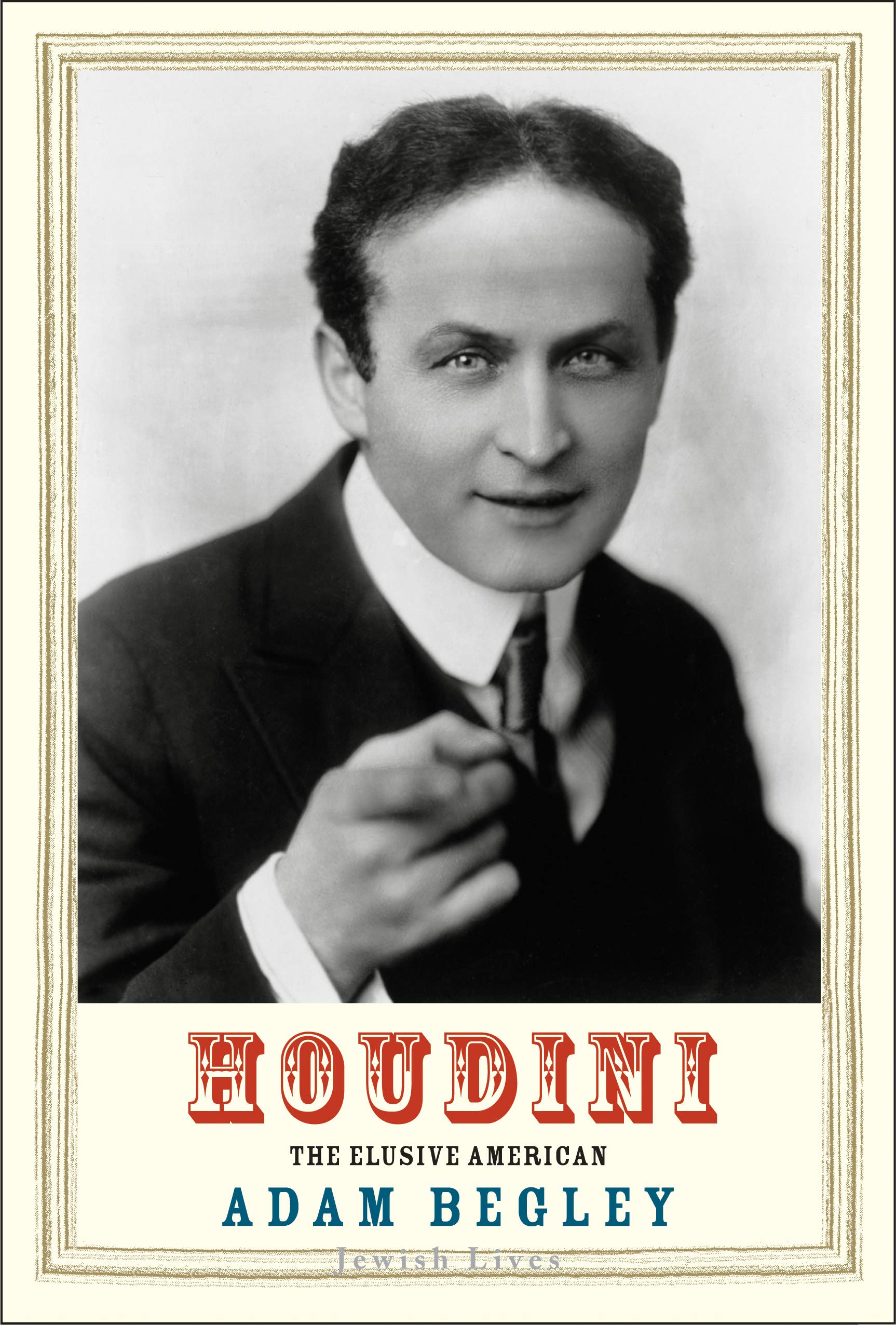

“Houdini: The Elusive American” by Adam Begley

Adam Begley’s micro-biography of Harry Houdini is one of the latest entries in Yale University Press’s impressive Jewish Lives Series. The book, also an excellent addition to the vast library of Houdini books, is very much in keeping with the publisher’s intention to present these books as interpretive biographies—books meant to “illuminate the many facets of Jewish identity.”

Born Ehrich Weiss in Budapest to a rabbi and his wife, Houdini and family immigrated to Wisconsin when he was 4 years old. Rabbi Weiss became the leader of a small Jewish community made up of just 15 families until he was fired for being “too attached to his Old World ways.” The rabbi moved the family to Milwaukee, where he struggled to make a living as a mohel and kosher butcher. The family eventually relocated to New York City, where the rabbi died of cancer at the age of 63, leaving his wife and seven children.

Ehrich, who was 18 at the time, dropped out of high school to support the family as a magician. Begley notes the move was Houdini’s “ticket out of poverty: he would become an entertainer.” Soon after, Ehrich Weiss adopted the stage name Harry Houdini, in tribute to the 19th-century French magician Jean-Eugene Robert-Houdin. Houdini added his own flair with an extra “i” at the end.

Houdini was a compact man, yet he cultivated an air of masculinity. His stage partner was his diminutive wife, Bess, whom he regularly “sawed” in half and “disappeared” only miraculously to appear again. Houdini’s performances became increasingly riveting and dangerous. One of his most notable tricks was the “water torture escape,” which he introduced in Berlin just before World War I. Shackled and hanging upside-down in a coffin-like booth filled with water, the curtain closed and an anxious audience waited for Houdini to arrive. A few moments later, an exhausted, gasping Houdini emerged to a cheering audience.

Houdini, the small man who always escaped, became a symbol in a century filled with group incarcerations, mass murders and genocides. He died on Halloween night in1926. As Begley notes, contrary to urban legend, Houdini did not die from a punch to the stomach but of a burst appendix and peritonitis unrelated to the punch. Just before his death, he insisted on performing with a raging fever. He was 52 years old. And as Begley insightfully observes: “Houdini was not interested in the meaning of his stunts, and in a sense they were meaningless. They accomplished nothing. They advanced no cause, proved no point. …He liberated only himself.”